How a Fun Guy Goes to the Woods and Photographs Glowing Mushrooms

![]()

I often hear my students lament about how if only they could travel to the rainforest they would find something really interesting to photograph. I tell students “look around where you live – there are wonderful things to photograph everywhere”. The photographers that work with local species often obtain shots that are unobtainable from casual travels.

The best samples of P. stipticus are found on fallen oak trees that have been rotting on the ground a few years. It is relatively easy to identify once you know what to look for. (This is the only mushroom species I can identify with 100% certainty). In New York, the best time to collect P. stipticus is usually the last two weeks of September. However, this year (2018) has been especially hot so the mushroom seems to be having a bumper year. I am still finding prime examples in the second week of October.

My experience with this unique mushroom started in my old office in 1999. My office was situated in a building that had no air conditioning and was tucked behind a classroom with no windows. In the winter, the office was 80°F while the rest of the building was in the mid-60s. Many of my fellow teachers wondered why I liked my windowless office, but I figured I had better keep my reasons to myself.

One day, during office hours in the fall a student exclaimed “this office is hot enough to grow mushrooms!” and I thought to myself what an interesting idea. Of all the things I could grow in my office I was looking for an interesting native species Panellus stipticus fit the bill. A local mushroom club offered up some samples of the fungus just in time (before the first killing frost). Over the course of a year, I figured out how to grow and purify the strain. Students would often visit the office just to check out the glowing mushrooms and of course everyone called me a “fun-guy”.

![]()

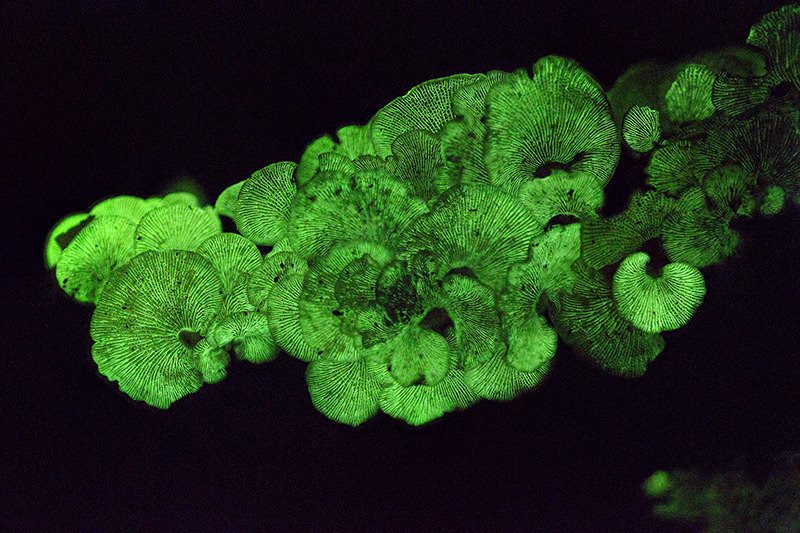

To see the glowing fungus with your eyes it is best to allow your eyes to become adapted to the dark, a process that can take 20 minutes for best results. My first successful photographs of the fungus were with Kodachrome 64 at f/1.2 and an exposure of 20 hours.

These days I no longer grow the glowing mushrooms, but often pick up some samples that look especially good during hikes in the fall. I use P. stipticus to test the low light ability of various cameras. To say that low-light capabilities of cameras have changed a lot over the last 20 years is an understatement. What used to take me 20 hours to photograph on film; I can now collect in 30 seconds.

The following images were collected with two different cameras that I consider to be especially good. When shooting low light conditions, be sure to turn on the noise reduction filter on the camera. The camera will collect an exposure then close the shutter, and collect a second exposure from the sensor that is used to reduce the noise from the desired exposure. This technology has become so good in the last few years that it has opened up a whole new area of low light photography which will be the topic of another article.

The green glow is attributed to luciferase, an oxidative enzyme, which emits light as it helps the fungus digest the toxic tannin in the oak. To increase the brightness of the emitted light, the fungus can be fed a dilute mixture of pectin in water.

It is still a mystery why the fungus has evolved to emit light. The process must be of some benefit to the organism but we just do not have an answer yet. We can add this as just another mystery that the northern woodlands still hold.

I would like to challenge readers of this article to get out in nature and see if you can not only photograph this species but have a try at the numerous other organisms that give off light. I suspect there are still organisms that glow so dim that we cannot see them with our eyes, but the camera can!

About the author: Ted Kinsman is an assistant professor of photographic technology at the Rochester Institute of Technology. He teaches advanced photographic technology, light microscopy, and macro photography courses. Kinsman specializes in applying physics to photography. You can find more about him and his work in his faculty profile and on his website.