Otherness and the Fetishization of Subject

![]()

A dark reality exists within photography that few photographers are willing to discuss and many refuse to even recognize. In the name of purity, we tend to see photography as a medium that couldn’t — shouldn’t be able to — do harm.

Photographs that show poverty both domestic and abroad, show us destruction of our national infrastructure in the form of ‘ruin porn,’ and depict indigenous tribes only in traditional dress, all work to perpetuate a stereotype that clouds our world view.

These patterns that we see in contemporary photography are the result of an audience who demands that artists present to them the world in a very specific way. Those photographs which may stand in contrast to the ideas we hold most dear are often rejected by being described as showing nothing special. To show us the reality of things becomes an impossible task for the photographer so they resolve to presenting extremes in hopes that these shocking images may gain some recognition.

The world has been bombarded with books, articles, exhibitions, prints, posters, etc. all declaring they have uncovered something special about our world and without fail, the audience follows the photographer down this road of half-truths. It’s a scenario that continues to repeat itself.

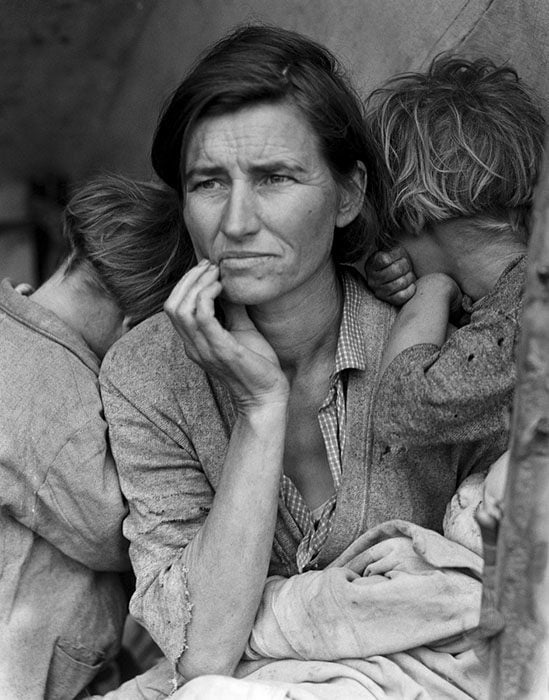

Dorothea Lange’s famous photograph, taken on assignment for the Farm Security Administration, depicts a mother of middle-age sitting quietly, hand to cheek while her two children flank her, their faces turned from view. Their clothes appear torn, tattered and dirty.

The mother’s face emotes a sense of longing, calmness, and a feeling of hopelessness. This image became the face of poverty in America in the wake of the Great Depression and Lange’s own statements about the photograph serve to amplify the story that emanates from that image:

I did not ask her name or her history. She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that [she and her children] had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food.

The story that Dorothea Lange tells is captivating and perfectly accentuates the story that the image tells. However, it is not true. Years later, when the migrant mother, Florence Owens Thompson, was discovered, she told a much different story than the world had known. She described how she was only at the camp in Nipomo, CA (where the photograph was taken) because her car had broken down. The story that she had sold the tires from her car was fabricated by Lange to propel this image from sorrowful to devastating.

Dorothea Lange purposely descended on the migrant mother at the camp and crafted her portrait in a way that would tell a very specific story; a story that Lange created before she had ever met the mother. While this image is iconic and the work that Dorothea Lange did was no doubt significant in helping the victims, it shows just how far photographers are willing to go to push a narrative.

The American people fetishized the idea of poverty and Lange exploited that when she made this photograph.

The legacy left by Lange is carried on by a army of photographers today. Especially with the ease of access to photographic expertise provided by the digital age, droves of photographers have flocked to the most destitute regions of our country vying for fame by documenting the destruction left behind by the end of the Industrial Age. This comes in the form of a new genre of photography generously dubbed as ‘ruin-porn’.

A common trope, these images are all the same and do nothing to provide relief. Instead, they perpetuate an almost nostalgic sense of beauty in the destruction of American infrastructure.

The poster child of this kind of photography is Detroit, Michigan. This is a city that once held regal status among industry and was the epicenter of automobile manufacturing. With the fall of that empire the economy quickly crumbled. We all know the story and we’ve all seen the images. A wide angle photograph taken inside the heart of an abandoned building, perfectly composed to force the viewer into the image, imagining the building in its prime. The windows are broken, ceilings cave under the pressure of disrepair and nothing is left intact save the structure itself. Our heartstrings are pulled and leave us yearning for things to be great again.

Meanwhile, photographers wander across the desert of Southern California. They find tranquility in the abandoned homes and buildings of the Salton Sea and seek to leave their mark. Abandoned cars dot the landscape. Hotels that once served vacationing families are empty and their pools drained. Garbage and remnants of a life once lived seep from the ground. We’re reminded of death and how fleeting life can be. How quickly our lives can be reduced to nothing. But we expected this photograph just like we expected the photographs before it.

In history books live tales of other people whose lives are simple and happy. They live within small communities we call tribes. These tribes have been living this way for thousands of years. Completely cut off from modern society or simply refusing to be a part of it, they live in a way that many romanticize as a pure society without troubles and whose connection to the natural and spiritual worlds are pure.

So, photographers with pockets deep enough to warrant travel to these villages embark on journeys they tell themselves will help to illuminate a life vastly different than the one many of us live. The images they return with are met with praise of originality and innovation but they are far from either of those things. These images are expected and usual: a woman stands in a formal pose against a black background, her fingers intertwined. Soft light, presumably from an artificial source gracefully covers her partially naked body and forms around her smooth black skin. She stares into the camera, her lower lip hangs and wraps around a large clay disk.

The jewelry in her hair hangs gracefully upon her shoulders. Bands cling to her arms in the spaces between her patterned scars. A wrap made of animal skin slings over one shoulder covering one breast but exposing the other. The time in which she is alive is unclear, as she represents a traditional way of life. This is an image taken by a German photographer, Mario Gerth but it could have been taken by any other.

![]()

As photographer Stuart Franklin writes in his book The Documentary Impulse, documentary photography has a very deep-rooted past in this type of ethnography. Franklin describes the methods some photographers used in the early 1900s where they would paint in tattooes, purposefully place jewelry on subjects and pose them in a way that fit the stereotypes of who the world wanted these people to be. These images were incredibly powerful in shaping how the West viewed other cultures. This method of photography forms a fracture between reality and fantasy. We now expect to see certain images from these places that don’t inform any truth about a region or a people, but simply feed a western fetish of sensationalist other.

This type of photography becomes admirable in its reception by the media world. Photographers like Mario Gerth, Joey L and Steve McCurry are given praise from around the photographic community for being willing to endure such hardship and crafting such beautiful and truthful images of other cultures when in reality there is nothing new being shown to us. Nothing out of the ordinary is revealed and the narrative refuses to budge.

It’s locked in place, perpetually trapped in a revolving door and trying desperately to escape. Every time a new voice begs to come in, they’re told it’s full and acceptance is denied. Only those who “fit in” are given access. So the story is told and the story is the same. For decades we’ve seen this happen. The act of forcing our subjects to fit a specific mold and then calling it documentary photography is a perversion of the term and serves only to weaken the effect of the documentary narrative.

As a photographer, it becomes increasingly easy to form an idea in your head of what something should look like and then use your tools to force that image into existence. Although more than a century has passed since photographers were stripping women of their clothes and painting in tattoos, the narrow western view of the world is still influencing the way in which we forge truths into photographs (and vice versa) and how we manipulate our subjects into fitting a narrative rather than letting them inform it.

I am not at all attempting to arrest photographers in their efforts to document other cultures sometimes with images that may speak to a truth rather than be true themselves. What I hope is that by recognizing our fixation on certain aspects of contemporary life like poverty and tribal life, we can begin to remedy the damage done. When all we see are the same tired images of people or when a photographer pretends that their images are capable of defining even a small aspect of another culture, the lens through which we see the world becomes ever more narrow.

Our response to global issues becomes crushed by the weight of our perception of someone else’s needs and when those two things become so polarized by perpetuated stereotypes, we end up hurting them. The simple act of allowing someone to photograph you is a generous courtesy that should be reciprocated by honoring that person with a photograph that reflects their reality and experiences, not burdens them with falsities and misconceptions.

You can find the archives of Alex Thompson’s column here.

About the author: Alex Thompson is a documentary photographer living in California’s Central Valley. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. His work focuses around environmental issues and the social consequences of environmental degradation. His work has been featured in publications like LA Weekly and The Guardian US and he is currently working on long term projects documenting the effect of extraction in Wyoming and life in communities along the SF Bay-Delta. You can find his work at www.alexthompsonphoto.com or on Instagram @alexthompsonphoto.

Image credits: Header photo illustration based on image by jmv and licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0