How Ansel Adams Wrote Pictorialism Out of Photography History

![]()

We all have a blind spot, both literally and metaphorically. Ansel Adams had one so big and powerful that he, Beaumont Newhall, and a few others “disappeared” some very important and wonderful photographers from the history of photography. And in doing so they also helped “disappear” an important movement in photography, one called Pictorialism.

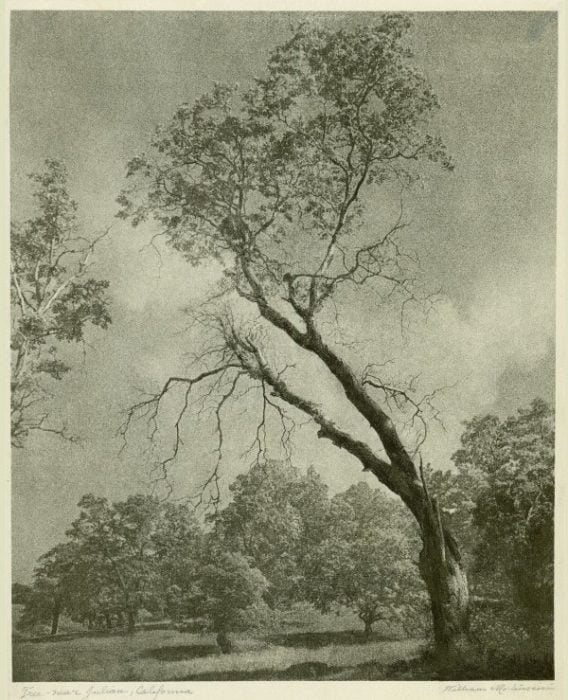

Pictorialists were concerned with making images about feelings and they used every kind of technique they could imagine to get the job done. Soft focus, multiple images layered on top of one another, texture screens, painting on negatives and prints — any and all of these could be used to modify the straight negative the camera produced.

Pictorialism flourished as a photographic style from 1885 to somewhere in the 1920s. Many early photographers, people like Julia Margaret Cameron , Edward Steichen and Heinrich Kuehn either were or began as pictorialists. In fact, Ansel Adams started out as one too, but after falling under the spell of the F64 School, he abandoned pictorialism and turned vehemently against it.

The F64 crowd believed that only a “Straight” image was photographically pure, once you modified what the camera had seen you had wandered from the path. And if straight photography was “better,” then Pictorialism had to be “bad,” and photographers who practiced it were also “bad” and could be ignored or vilified.

Since Adams and Newhall were aligned aesthetically and since Newhall wrote the seminal The History of Photography, important Pictorialists like William Mortensen and Elias Goldensky were written out of the history … and we lost a great and beautiful tradition. With no establishment recognition, the techniques of Pictorialism were for the most part forgotten and the world marched on.

Except beauty never goes away, even as our idea of what constitutes it changes. And straight photography couldn’t contain all the ideas about beauty that people might have. So the practices of Pictorialism crept in around the edges: a soft focus shot here, movement portrayed as a blur there. As long as it didn’t have a name or school, it didn’t draw the wrath of the straight photography purists.

And then digital photography came along, and Photoshop appeared, and suddenly we were back in the age of Pictorialism, only without the aesthetic discussions that were the underpinnings of Pictorialism as a movement.

To learn more about the concepts of Pictorialism you have to go back to the photographers who wrote about and practiced it and understand what they were thinking about when they made their images.

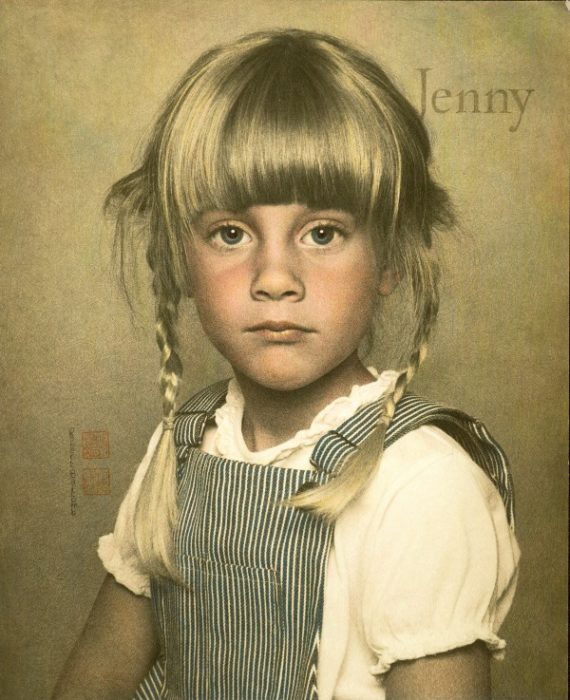

William Mortensen was an extraordinary stylist and for many years perhaps the best known of the 20th century Pictorialists. His feud with Ansel Adams was legendary, although their attitudes towards the differences were not well matched. Mortensen separated the man from the artist, while Adams hated both Mortensen and his work intensely.

Even years after his death Adams could find little or nothing nice to say about him. In retrospect, although Mortensen’s subject matter was often grotesque and sometimes fell into the kitschy, his mastery of craft was and is astounding. Most people seeing a Mortensen print for the first time find it hard to believe it is a photograph.

Mortensen pioneered techniques like printing a negative onto paper, shading the back with a pencil to hold back the highlights, printing the result onto another piece of paper, shading the back again (this time to darken the shadows of the now negative image) and printing the result a third time, perhaps through a texture screen to make a positive image of extraordinary textural and tonal qualities.

If there is an artist who thoroughly understood and foreshadowed the possibilities of Photoshop long before it appeared, it would be William Mortensen. In the last few years there has been a resurgence of interest in Mortensen. An internet search will turn up reprints of his books and many examples of his work.

A more modern example, Robert Balcomb studied extensively with William Mortensen and went on to make portraits using Mortensen’s techniques for over forty years. His book, Me and Mortensen — Photography with the Master, is a reminiscence, a showcase for images made in the Mortensen manner, and a primer on analog photographic techniques, many of which can be applied in the digital world. The printing is beautiful and the book is well worth having on your shelf.

Mortensen and Balcomb are a small sampling of pictorialist expression available online and in new and used book stores. They offer a glimpse into the thinking that was informing image making a century ago. Today we have thousands of tutorials about how to do almost anything in Photoshop but very little talk about why we make pictures, or the intention behind them. The F64 School opened the door for generations of sharp and beautiful images, but at the cost of leaving behind a whole other way of thinking about the picture.

A hundred years ago photographers were having serious discussions about the aesthetic why of making pictures as well as the how. They wrote and argued passionately not about which camera or lens was better but which way of thinking got them closest to their desired result. For the pictorialists the image was a way of encapsulating emotion first, rather than a photographic fact. Maybe it’s time to call people who do that now 21st century pictorialists and start the discussion again.

A different version of this story first appeared in L’oeil de la Photographie a few years back. Thanks Jean Jacques for giving me the first opportunity to write!

About the author: Andy Romanoff is a writer, photographer, photojournalist, and a few other things besides. The opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author. To see or read more of Andy’s work, visit his website or give him a follow on Instagram and Medium. This piece was also published here.