Nat Geo Says It’s Committed to Honest Photos In an Era of Photoshop

![]()

National Geographic‘s editor in chief has published an editorial in which she reaffirms the magazine’s commitment to keeping “photography honest in the era of Photoshop.”

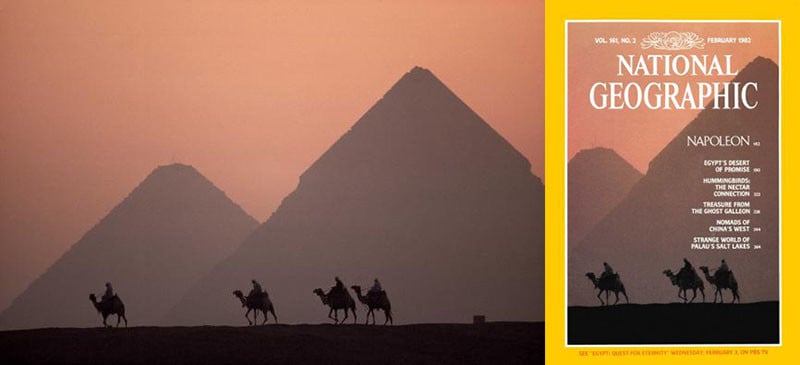

Back in February 1982, a Nat Geo cover featured a shot by Gordon Gahan of a camel train in front of the Pyramids of Giza. The original shot was in a landscape orientation, but the magazine’s editors decided to alter the image, squeezing the main subjects into a vertical frame so that it would fit the iconic yellow borders:

Nat Geo says it has learned a lesson since this photo was published. There was a swift public outcry at the time, and more recently the edit was brought up again in the wake of the controversy surrounding photographer Steve McCurry’s work, some of which is accused of being Photoshopped and staged.

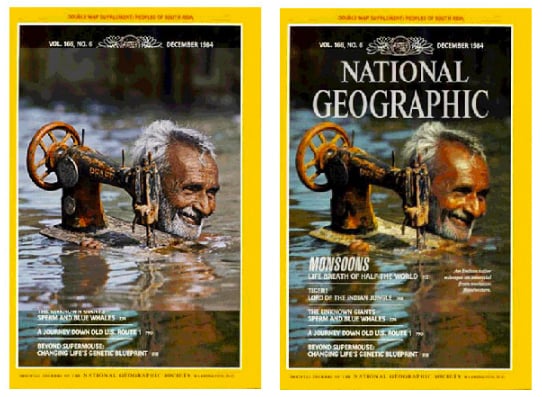

McCurry argues that ethical standards in the photojournalism industry have shifted over the past decades, citing National Geographic‘s old cover edits as examples. One of his cover photos was also heavily edited by the magazine to fit the frame:

Like McCurry, Nat Geo says it has learned its lesson and that its current policy is different from the past.

“At National Geographic it’s never OK to alter a photo,” Goldberg writes. “We’ve made it part of our mission to ensure our photos are real.”

National Geographic now requires that photojournalists submit RAW files of the images they send in, allowing the magazine the examine the original, untouched pixel data captured by the camera.

“If a raw file isn’t available, we ask detailed questions about the photo,” says Goldberg. “And, yes, sometimes what we learn leads us to reject it.”

The critical question Nat Geo now asks is: “Is this photo a good representation of what the photographer saw?”

“For us as journalists, that answer always must be yes,” concludes Goldberg.