These Were the First Wildlife Photographs Published in National Geographic

![]()

Did you know that after National Geographic published its first wildlife photographs in July 1906, two of the National Geographic Society board members “resigned in disgust“? They argued that the reputable magazine was “turning into a ‘picture book'”.

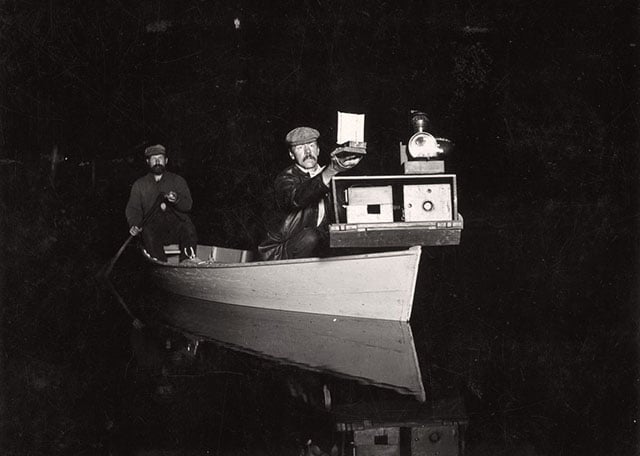

Luckily for us, it did turn out to become quite a picture book. Those first wildlife photos published in the magazine were captured by George Shiras, III, and marked quite a few “firsts.”

To achieve his shots, Shiras pioneered a number of different photo-making methods. One was to float silently across water in complete darkness. When he heard rustling nearby, he would point his camera system and snap a flash photograph in that direction.

A second method was a custom-designed camera trap system (the first of its kind) that used a trip wire to activate a magnesium flash gun. When animals would attempt to take the bait attached to the wires, they would trigger their own photograph (and a flash that was powerful enough to temporarily blind both Shiras and the animal).

As a result of his ingenuity, Shiras succeeded in capturing the first nighttime wildlife photographs ever created. They were the first wildlife images to use both flash photography and camera trap equipment.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In 1905, Shiras brought a box of his photographs to National Geographic. Then-editor Gil Grosvenor liked them so much that he dedicated the July 1906 issue of the magazine to publishing 74 of them. It was a single-article issue titled “Hunting Wild Game with Flashlight and Camera.”

Remember those two National Geographic board members that resigned in protest? Well, in 1911, half a decade after Shiras’ photographs appeared in the magazine, the photographer himself was named to the Board of Managers.

Wildlife photography has also become one of the defining features of what National Geographic is all about.

P.S. Shiras was also a conservationist who advocated for “camera hunting” as an alternative to the sport of gun hunting. Among his supporters was President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed camera hunting could help “conserve game while developing hardihood.”

Image credits: Photographs by George Shiras, III/National Geographic