‘Humans of New York’ Sends Back Powerful Portraits and Heartbreaking Stories from the Middle East

![]()

It’s getting to the point where you’d be hard pressed to find anybody who doesn’t already know about Humans of New York, Brandon Stanton’s project turned photobook turned international phenomenon. But that became even harder this week when Stanton took the project on the road with the UN and delivered some of his most powerful portraits from the streets of, not New York City, but Iraq.

Stanton has been operating from the war-torn country as of August 7th as part of a 2-month UN World Tour, and since then, the project’s following on Facebook has jumped by nearly a quarter of a million people.

This is no accident either. The impact of the intimate, life-affirming style that has earned Stanton millions of admirers is somehow multiplied 100-fold when the people he is talking to are often fighting for their lives and struggling with issues that most of his followers couldn’t even imagine.

Humans of New York is, after all, a project about humanity. The reason New York City works so well is because Stanton is never short of interesting people whose experiences vary as widely as their birthplaces. Taking the project on the road is just a way for Stanton to “listen to as many people as possible,” and share what they’re saying with us.

“We hope this trip may in some way help to inspire a global perspective,” writes Stanton, “while bringing awareness to the challenges that we all need to tackle together.”

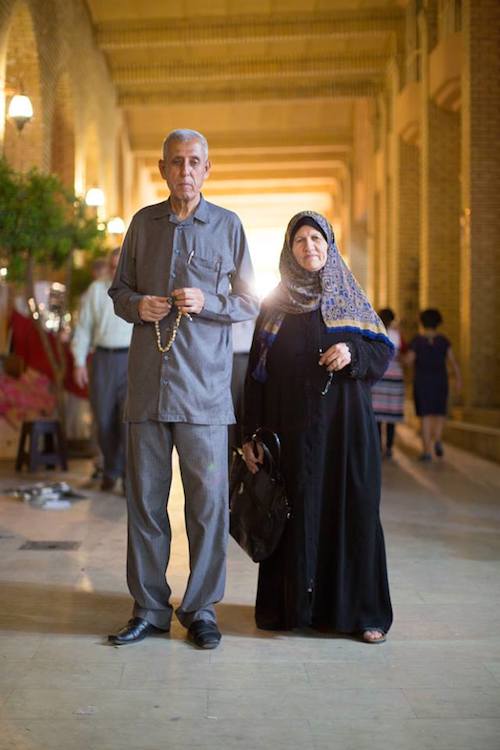

The images he’s sent back so far range from heartwarming to heartbreaking, with a heavy natural slant towards the latter. Here is a selection of photos, complete with captions, that he’s uploaded from the Middle East:

The project began in Iraq, but already Stanton has moved on to Jordan and he will visit eight more countries before it’s all said and done.

The goal with these images, beyond simply sharing stories he would never have the chance to share from NYC, is to promote the eight Millennium Development Goals UN member states hope to achieve by 2015. But what you see above and what you’ll find if you follow Humans of New York in the coming weeks goes beyond the UN’s goals, however noble.

As they do in New York, his images from Iraq and the rest of the Middle East magically transcend the politics of borders and biases. When we see his portraits and read the captions, our differences drop away.

If only for a moment, we are just humans, staring into the eyes of another human, listening with rapt attention to the their story.

Image credits: Photographs by Brandon Stanton/Humans of New York and used with permission