A Detailed Look at the Camera Gear Behind the Historical Apollo 11 Moon Landing

Only NASA could turn photography into literal rocket science. As Reddit user truetofiction points out in a resource-rich post, NASA meticulously decided upon a number of factors that determined the fate of the space-bound Hasselblads and the resulting images.

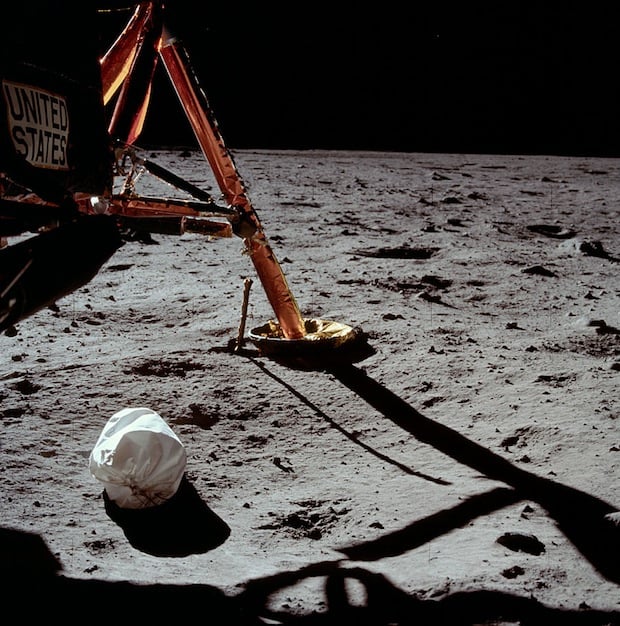

When Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong separated from the Command Module of the Apollo 11 mission, their moonscape-destined Lunar Module had two Hasselblad cameras in it. Each served a distinct purpose and each had a number of features purpose-built for their individual endeavors. Before we break down the differences though, we’ll establish what the two models had in common.

Both built around the Hasselblad 500EL body, these two cameras featured a mostly-automated process, thanks largely in part to the electronic motor. The astronauts needed only to set the distance, aperture, and shutter speed. Once the shutter was pressed, the frame was exposed, the film was wound to the next frame, and the shutter was reset.

Other features present to these two cameras was the use of special-designed locks for the film magazines, levers for the aperture and distance settings and featured a simple sighting ring, rather than a reflex mirror viewfinder.

![]()

The first of these was for use inside of the Lunar Module cabin. It was called the IntraVehicular Camera (IVA). This particular Hasselblad featured a black paint scheme, lacked a reseau plate (the grid you often see in the photographs from early space missions) and packed an Planar 80mm f/2.8 lens.

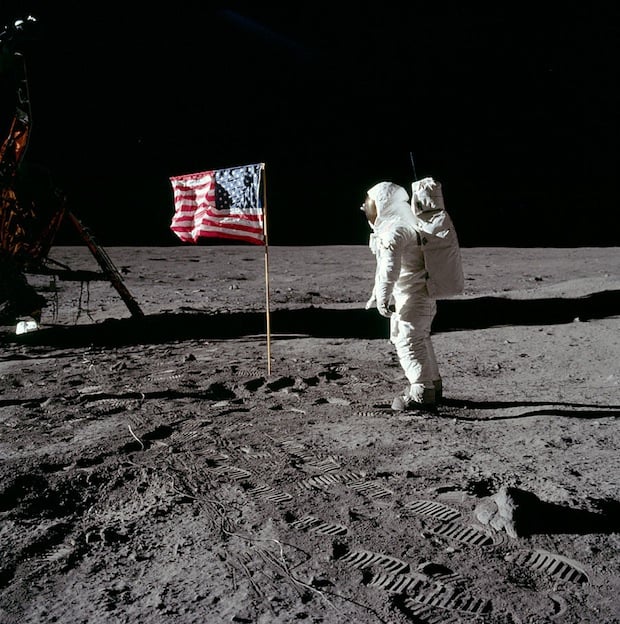

The second of these was for use outside the Lunar Module cabin and featured a number of more precise additions. Called the ExtraVehicular Camera (EVA), this beauty had anodized surfaces to prevent the possibility of overheating, included a reseau plate, and used a wider, Planar 60mm f/2.8 lens. In addition to those features, this model needed to get rid of the conventional lubrication within the camera’s mechanical parts, as it would boil off in the atmosphere and potentially condensate onto the optical elements.

With all film magazines painted to match their respective camera bodies, the astronauts had three magazines loaded with 70mm film: two color and one black and white. While the specifics of the film used in Apollo 11 aren’t noted, records indicate the same emulsion used on Apollo 8 was used in the Apollo 11 mission.

Thus, we can conclude that the magazines were loaded with the special-designed film NASA contracted Kodak to develop. For black and white they used 70mm perforated Kodak Panatomic-X ‘fine-grained’ film with an ASA rating of 80. For color, they could’ve used any combination of Kodak Ektachrome SO–68, Kodak Ektachrom SO–121, and Kodak 2485, the latter of which featured a ‘super light-sensitive’ ASA rating of 1,600.

It’s incredible to think about how much work went into the creation of special-designed equipment for the documentation of our endeavors to the moon. Whether you’re a believer of it or not (and Buzz Aldrin has a little surprise for those of you who aren’t), it’s an astonishing feat.

As pointed out by Reddit user seriouslyawesome, it’s interesting to think about how integral photography has become to almost all space-related sciences. Up until the advent of the ability to capture light via photographic means, it was almost entirely up to human representation and replication, albeit with the help of other scientific tools.

To roughly paraphrase the late Steve Jobs: Here’s to the crazy ones. The astronauts. The scientists. The literal rocket scientists amongst us plebs.

To read up more on the camera tech behind the Apollo 11 mission and more, you can check out a number of resources, here, here and here.

Image credits: Public Domain images provided by NASA