Vagabond Photographer Shot 5,000 Photos of Rural Life That Were Found Years After His Death

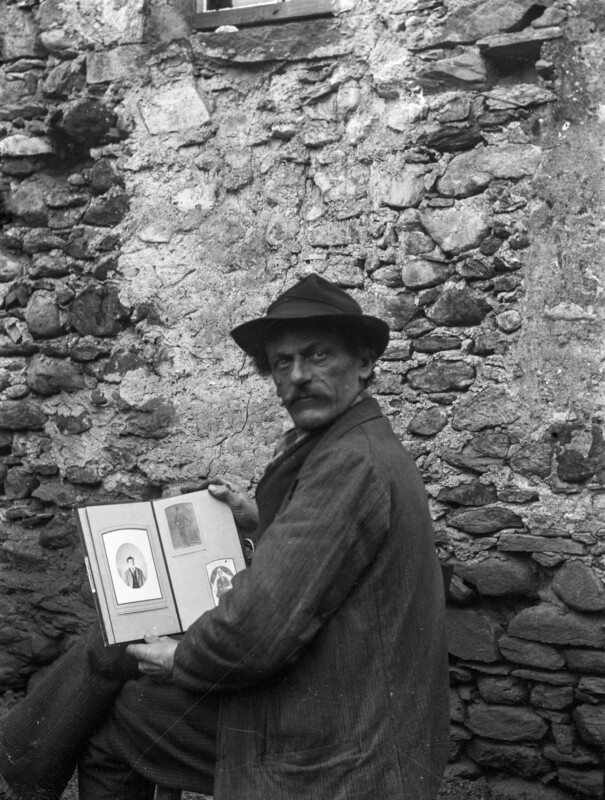

Striding over the steep inclines of the Swiss Alps in the late 19th century, a tall, mustachioed, eccentric man — who would often sing to himself — traveled around the impoverished Blenio Valley hawking seed packets while carrying something else: a large format plate camera.

Roberto Donetta is a very unusual photographer. He died as he was born, penniless and bitter about a world that he could not navigate and that he never truly found satisfaction in. And yet his photos are bursting with humor and intrigue thanks to his clever use of composition and his ability to put subjects at ease.

In 1912, his wife left him and took six of their seven children with her as he was unable to provide for them. On his 46th birthday, all of his belongings — including his beloved glass plate camera — were seized from him.

Most men born in the Blenio Valley left to find work in a nearby industrialized town. But Donetta, partly because of his love of nature, never left the countryside that he so adored, lamenting the changes as roads were built and new railway lines installed.

The Fotostiftung Schweiz, which exhibited his work, called Donetta a “contradictory personality” since his love of technology, namely photography, clashed with his Luddite persona.

It ultimately led the villagers of Blenio Valley to regard him as a vagabond. But despite his shifty reputation, it’s clear that he was well-liked, and many villagers would request his photographic services; although he would often deliver commissions late because he would develop plates infrequently to save on chemicals.

After he died in 1932, the 5,000 photos he had taken were the only items that auctioneers could not get rid of at a sale of all his belongings to aid those who had lent him money and never got it back.

It wasn’t until the mid-1980s that Mariarosa Bozzina discovered his life’s work in Corzoneso, the rural village where he had died. Donetta’s incredible photos depict yesterday’s world that was being left behind.

Although Donetta didn’t own a shop, he would attempt to recreate late 19th-century photographic studios by hanging his own improvised backdrops and using whatever props he could lay his hands on.

The Fotostiftung Schweiz says it is “evident” that Donetta’s technical prowess improved greatly over his 30-year career as he got his pictures sharper and better composed.

“Over time, Donetta proceeded to photograph his figures outdoors, in nature, embedded in a scenario that was very familiar to him,” the museum adds.

Image credits: Photographs by Roberto Donetta