The Awe-Inspiring Finalists for Ocean Photographer of the Year 2025

The finalists for Ocean Photographer of the Year 2025 have been officially revealed, showcasing breathtaking images that celebrate the ocean’s beauty and highlight the urgent need to protect it.

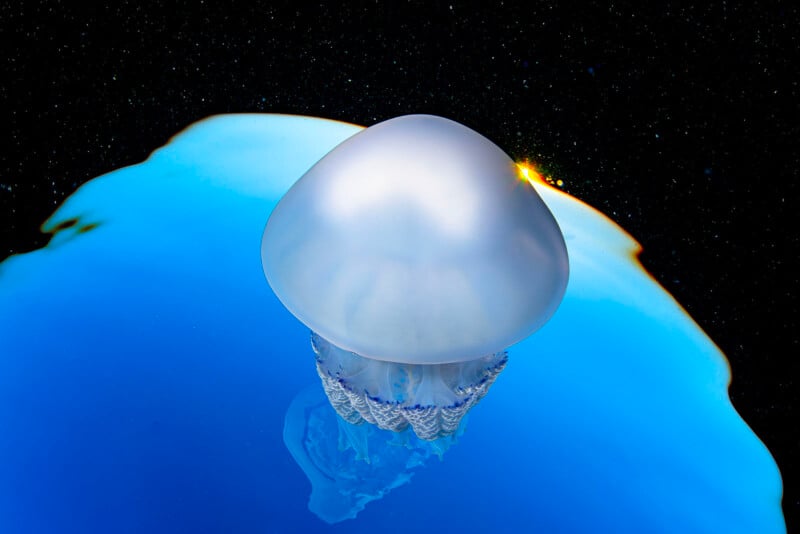

This year’s submissions include extraordinary moments of wild ocean wonder, such as a marine iguana ‘mid-sneeze’, a troupe of skeleton shrimps that has colonised a gorgonian coral, and a spaceship-like jellyfish that appears to be departing Earth’s atmosphere.

“In the midst of a deepening climate and biodiversity crisis on our blue planet, ocean photography has never been more important. These images are far more than just beautiful – they are powerful visual testaments to what we stand to lose, and they remind us of the urgent need for protection,” says Ocean Photographer of the Year director Will Harrison.

Adventure

Impact

“This image represents one of the most profound moments of my life,” says Moreno. “It was my first year in Exmouth, drawn by the stories about Ningaloo Reef. With just a kayak and an obsession with the ocean I explored the reef weekly. On this particular day, a friend and I went to Turquoise Bay, where we encountered this humpback whale, hopelessly entangled in fishing nets, chased by dozens of sharks. In a moment of desperation, knowing it was beyond us to help, I tried to document the situation. I hope this image turns tragedy into awareness, inspiring real change for our ocean.”

“Fear, fuelled by films like Jaws, blinds us to the truth: more than 100 million sharks are killed each year by humans – many as accidental bycatch,” says Flormann. “I captured this image in West Papua, where three sharks died in a net meant for anchovies. Nearby, the half-cut-off caudal fin of a whale shark tells another sad story of human impact. Sharks are essential to ocean balance, yet we are driving them toward extinction. This moment is a quiet plea: to see sharks not as danger, but as endangered – and worth saving.”

“This green turtle was killed by a boat strike, an unnatural and unnecessary death for an endangered species,” says Spiers. “Only recently deceased, it is partly decomposed, with the haunting view of the bare skull in contrast to the skin, which remains on the rest of its body, and the juvenile fish which have adopted the turtle carcass as a form of safe refuge. We came across this turtle by chance, a dispiriting sight at the end of a long and fruitless day at sea. I can only hope that this image acts as a reminder of the enormous human burden placed on turtles and the ocean as a whole.”

A long-finned pilot whale foetus lies lifeless under its mother’s corpse in the Faroe Islands. “Each year, more than 1,000 cetaceans are killed during grindadráp, the slaughter of entire whale groups, including juveniles and pregnant females,” says Bret. “Usually, the foetuses are ripped from their mother’s womb far from the public gaze, but this pregnant female was undetected and eviscerated among the others, revealing this deeply moving scene. While these hunts were once an existential necessity, they are no longer subsistence practices. I hope this image drives global attention to end the grindadráp and, at a broader scale, advocates for a reconsideration of what the human relationship with others living beings should be.”

“Over the past 20 years, krill fishing has quadrupled,” says Kerdavid, “mainly to produce non-essential products like Omega-3 supplements, pet food, and feed for farmed salmon – used to make the flesh pink for Western supermarkets. A single trawler can catch up to 500 tonnes of krill per day. That’s enough to feed 150 whales. Less krill means less food for whales, seals, penguins, and countless other species. Today, krill extraction is one of the fastest-growing threats to Antarctic wildlife. That’s why Sea Shepherd is heading to Antarctica: to expose this industry and show the world what’s really happening: hungry whales following krill trawlers, desperately searching for food.”

Wildlife

A marine iguana lets out a sneeze.

An opportunistic pelican swoops in to steal a fish from strand-feeding dolphins in South Carolina.

Gentoo penguins.

Komodo dragon.

A young orca with a kill.

Human Connection

“In the early hours of July 1st, we received a call about a stranded humpback whale,” says Parry. “Wildlife veterinarian Steve Van Mill quickly assessed the situation and contacted SeaWorld Marine Rescue and other key agencies to coordinate a response. For 15 hours, rescue teams and the local community worked tirelessly in a unified effort to save her. Sadly, despite their dedication, she could not be saved. While the outcome was heartbreaking, witnessing the collaboration and compassion shown by multiple agencies and volunteers was incredibly moving – a powerful reminder of what can be achieved when people come together with a shared purpose.”

Fishing village in China.

“The behaviours exhibited by grey whales in their mating and calving lagoons in Baja California, Mexico, are unlike anything else seen around the world,” says Subramaniam. “They have a remarkable curiosity, actively approaching small fishing skiffs to see what is happening. I shot this on an incredible morning, when we had over 20 whales around our boat. The four that you see in this image were the initiators, after which all the others wanted in on a piece of the human action. To this day, this remains the most incredible wildlife interaction I have ever had.”

“Fuji 268, one of Taiwan’s last fire fishing boats, ignites a fireball to startle sardines in the coastal waters of New Taipei,” says Arunrugstichai. “By 2023, it was the sole survivor of this national cultural heritage of Taiwan, with the crew working to sustain the tradition by partnering with local guides and launching their own educational program to offset costs and dwindling fish stocks. The effort drew more than 5,000 tourists in 2024 – double the previous year – sparking enough demand for another fire fishing boat to return to operation under this growing business model.”

“On April 1, 2024, more than 20 Bigg’s orcas entered Puget Sound together,” says Ling. “At Point No Point, one of my friends was on the beach watching as the pods passed, when T099C “Barakat” – a male orca – suddenly began breaching repeatedly near the beach. At one moment, he leapt from the water just metres away from my friend. Although her lens was too long for the closeness, I happened to be offshore and captured the perfect shot for her, and this shot perfectly reflected the connection between the wild orcas and land-based whale watchers in Puget Sound.”

Fine Art

“I’ve always been fascinated by the resemblance between jellyfish and space rockets,” says Bertran Regàs. “I was looking for a photograph that conveyed that connection: a rocket leaving Earth. To do this, I used a fisheye lens and took the photo just as the sun was rising. Snell’s Window helped me create the Earth, the particles were the stars, and the sun luckily appeared behind it. I don’t think I’ll ever be as close to space as I was that day.”

“Dwarf minke whales are known to visit the northern Great Barrier Reef during the winter, making it the only known predictable aggregation of these whales in the world,” says Riederer. “These curious giants approach swimmers with an almost playful curiosity. Floating in the turquoise water, watching a sleek, dark body glide effortlessly towards you, its eye meeting yours in a moment of connection. The whales seem to acknowledge your presence, circling and interacting with you. It’s a humbling experience, reaffirming the wonder of the ocean and its inhabitants, and the urgent need to conserve it.”

Category winners, along with the overall Ocean Photographer of the Year (OPY) 2025, will be announced in September. All of the finalists can be viewed on the OPY website.

Ocean Photographer of the Year is presented by Oceanographic Magazine and Blancpain.