How a Towering 75-Foot-Long, 150 Million-Year-Old Dinosaur Was Rebuilt

A team of scientists and artists have spent the last decade excavating and reconstructing an incredible 75-foot-long dinosaur skeleton, and National Geographic has been along for the ride, documenting the detailed process.

“What a strange thing it must be to become a fossil. Say you live a full life for a Diplodocus dinosaur, swinging your enormously long tail across your Jurassic world for 70 or so years,” writes Richard Conniff in National Geographic‘s new exclusive feature story. “Then you die — but in such extraordinary circumstances that, against all odds, your bones are buried and transformed over time into stone. Mountains rise and wear away around you. Rivers come and go. Glaciers rumble overhead. Your bones endure.”

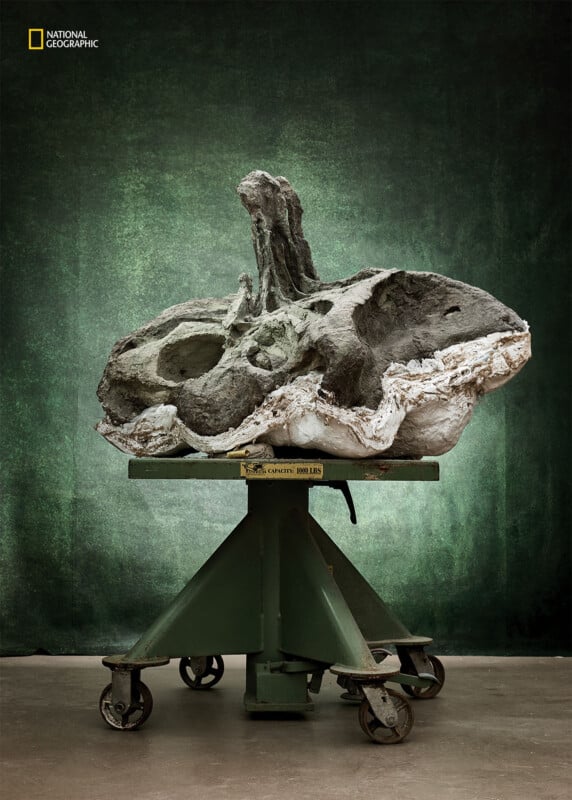

And then, 150 million years later, these bones return to the Earth’s surface in southeastern Utah, and “some unimaginable new species in a bizarre new world” digs them up, cleans and prepares them, and reconstructs them into a massive five-ton display. That’s the story of the sauropod dinosaur, now called “Gnatalie,” discovered after erosion revealed a single leg bone in 2007.

Now, calling the Los Angeles County Natural History Museum’s newest star, who will be unveiled to the public in November, “Gnatalie,” is a bit misleading as it suggests a single individual. The skeleton is not actually comprised of bones from a single long-necked dinosaur. Gnatalie, named for the stinging gnats that harassed the excavators, includes bones from two or more individuals of the same species fossilized at the same location. The species’ precise identity has yet to be identified and could be new to paleontologists.

Once all the bones were dug up, an arduous process, they were sent to the museum’s prep lab in Los Angeles. Experts used various tools to chip away the excess stone carefully. Any little holes were filled using specialized color-matched plaster.

Color-matching is quite the process with Gnatalie’s bones, as they have been infilled by a green mineral, celadonite, during fossilization, earning the dinosaur the affectionate title “Gnatalie the Green Dino.”

With all the many bones excavated and now prepared, Gnatalie made its way to a small Ontario town in the summer of 2023. Here, Research Casting International (RCI), a company that specializes in rebuilding dinosaurs for museums, prepared the skeleton’s skeleton. Fossils are held together using carefully crafted metal armatures.

The firm also performs necessary fixes for bones “distorted by eons underground.” This includes scanning and 3D printing substitute pieces, which artisans then paint to match the dinosaur’s real bones.

RCI is also responsible for working with museum staff to determine the best way to display Gnatalie, including positioning and posing. One challenge was that many of Gnatalie’s vertebrae were “crushed and twisted” during their 150 million-year slumber, which threatened the overall look of the entire display. The solution was 3D printing many spinal substitutes and displaying the actual fossils separately beneath the giant skeleton.

After years of digging and months of preparation and building, Gnatalie is in Los Angeles and undergoing final construction. “Gnatalie’s new life, as terror and teacher to our upstart species, is beginning at last,” National Geographic explains.

Image credits: National Geographic