One Man’s Trash: Parting Out Veteran Photojournalist Bill Green’s Darkroom

![]()

It was once common for professional and advanced hobbyist photographers to have small but capable darkrooms in their homes. Often tucked away discreetly in what would otherwise be unused spaces in basements and attics. Serious shooters would process their own film, craft their own prints, and store all the chemistry and idiosyncratic accouterment that one needs to control their own analog adventure.

Darkroom equipment like enlargers and driers were once as costly and important an investment as a good camera and lens. Built-in, custom items like sinks and cabinets were viewed as adding value to one’s home. Then there are all the little devices; processing tanks, reels, trays, tongs, clips, hoses, jugs, timers, thermometers, safelights, and all the chemistry to use with them.

![]()

After one makes the decision to finally get rid of all this stuff, the next question is what to do with it.

You might think it would be easy to sell fine, working equipment that cost thousands of dollars new only twenty years ago. But with so many darkrooms closing up and being parted out since the early 2000s, there has long been a glut of this equipment on the market. Buyers have their choice of the most premium darkroom gear now, in the most pristine condition. And unless you can sell locally, have fun with shipping and insuring delicate, sometimes backbreakingly heavy devices.

That’s not to say eBaying this stuff is impossible – have a look at the sold listings any time and you’ll be treated to a healthy number of quality items at reasonable prices. But this will require time; sorting, inspecting, testing, photographing, and describing.

Donating darkroom gear to schools was an obvious choice years ago until even the schools stopped taking it.

Some owners will just trash everything because it is often the easiest thing to do.

But people know that I still shoot film.

So every six months or so, I get an email asking if I’d be interested in somebody’s old darkroom gear. After acquiring the choosiest gear from my alma mater, a retired wedding photographer, and a few other serious hobbyists’ belongings, I have been politely declining and redirecting these requests to local film photography groups.

And to be perfectly honest, in some cases, I got the impression that people were just trying to unload crap on me, without appreciation for the art that I make with it.

But this summer, I got a message from Bill Green. He’s a well-known photographer for the Frederick News Post and has been covering local news for over 35 years – well before digital photography became standard.

![]()

Not only was my interest in taking on peoples’ old darkroom gear rejuvenated by the notion of inheriting a recognized, working professional’s stuff, but what touched me most was that Green followed my social media and understood how passionate I am about film photography.

I’m sure that with his connections in the community, he knew all the best people and places to offer his gear, but he chose me. And that meant a lot.

Bill talked excitedly on the phone about what he had and I was happy to listen. He told me about one item at a time and went into minute detail about how he used to use it and how great a piece of gear it was. He talked about film photography as if it was still his mainstay. It was clear that Bill cherished every stick of his old darkroom. And this made it that much more important to me to understand everything’s value and use whatever I could.

I arrived at the agreed-upon time in my “Home Depot Run” SUV with all the rear seats folded down, ready for anything.

Bill was very apologetic about how much of a mess his darkroom was in. I could tell that he was saying this not only because he’s a classy guy but it also felt like an apology for not keeping his film workflow going.

I’m primarily a wedding photographer so Bill told me about a conversation that he had with his daughter while they were going through her old wedding photos. He said she was unhappy with how grainy some shots were. Bill reassured her that he actually liked the grainy photos more than some of the really clean shots because “the grain obscured distracting details and allowed [him] to think about the actual memory.” Anecdotes like this showed me that Bill wasn’t just another photographer who went digital and forgot his love for film.

Bill’s darkroom was in his basement and consisted of a little ten-foot by twenty-foot side room. Unlike a hobbyists’ darkroom, Bill had quadruples, or more, of everything. And his equipment seemed to represent different time periods in photography.

![]()

Sure, he had the classic grey hammertone Time-O-Lite from the 1960s and huge, basic Gralab timers that we all used in school through the 2000s, but he also had fairly modern digital timers that I’ve only seen in commercial darkrooms. He didn’t just have a B&W enlarger but also a color enlarger too. The B&W one is a Leica Focomat Ic which Bill raved about as he pointed to its various features. It’s a beautiful work of industrial art compared to my garish blue and grey Beseller 3c that I used to think was a real prize. “Leica is Leica” we agreed.

![]()

Bill had boxes and boxes of specialized printing easels. Each was made exclusively for and marked with particular sizes that he commonly printed to. As he shuffled through them, pointing out that a couple were Leitz branded, he still knew, off the top of his head, what all their markings indicated and how large and small each could go.

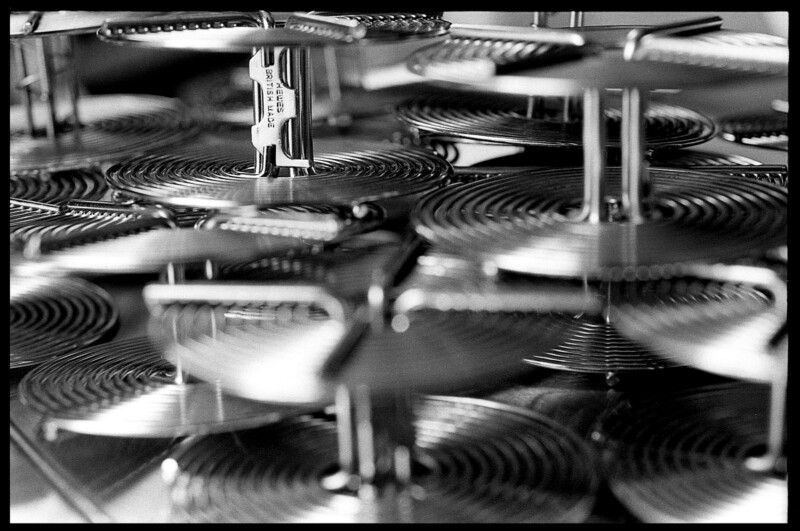

Like all the guys who use metal, Bill went on about why metal tanks and reels are so much better to use than plastic. He demonstrated with his eyes shut how to feel for the beginning of the spiral on which to thread the film. He shared old news photographer tricks like spooling two rolls of film onto a single reel, emulsion sides facing apart. This is the kind of stuff that an old pro will know how to do but today’s hobbyists who shoot a roll or two of 35mm a month would never dream of or have reason for. But, for someone like myself who shoots all his paid work on film, this insider info was great to learn about.

![]()

He had piles of press passes and posterity photos that he riffled through while sharing quick memories of helicopter tours, presidential campaigns, and exciting local ball games.

We came across a massive manual focus Nikkor 300mm f4 lens that only a news photographer would have been crazy enough to use! But Bill hadn’t picked up this special-use lens in years. Like many veteran photographers, he struggles to reliably focus long/fast manual lenses and has moved onto auto. Even with the diminutive Leica M6 hanging off my neck, Bill could see that this huge telephoto from another era piqued my curiosity. He generously passed it onto me like a metaphorical torch. And it’s probably about as large!

![]()

After two trips to Bill’s home, I safely transported everything that wasn’t nailed down. I had a blast sorting through all the do-dads and deciding what I could put back into use immediately, what I’d like to hold onto for future plans, and what equipment could find a better home with another film enthusiast.

It sounds silly but something of Bill’s that I use every time I process and am very grateful for are his vintage stainless steel film drying clips. New drying clips are flimsy affairs that fall apart and barely get the job done. The adage “they don’t make ’em like they used to” perfectly underscores how nice and strong the heavy old drying clips used to be. It’s satisfying every time I lock one onto the tail of my negatives and consider all the important rolls of film that Bill Green probably used them on. Items like these that may seem trivial to most, are the ones that I’m most honored to keep in use.

So look, I know that many of you veteran photographers have gone digital but I hope you know that there are still plenty of us who admire your legacy work and would be happy to hear about your methods and to keep your classic film equipment in service. Find us online and in your local community. Check out our work and what we’re doing to keep film alive. Pass on your old gear if you can bear to part with it. Or maybe consider firing up that old darkroom again and joining us.

Either way, the film community appreciates you!

About the author: Johnny Martyr is an East Coast film photographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. After an adventurous 20-year photographic journey, he now shoots exclusively on B&W 35mm film that he painstakingly hand-processes and digitizes. Choosing to work with only a select few clients per annum, Martyr’s uncommonly personalized process ensures unsurpassed quality as well as stylish, natural & timeless imagery that will endure for decades. You can find more of his work on his website, Flickr, Facebook, and Instagram.