How Photo Mechanic Was Born at Super Bowl XXXII in 1998

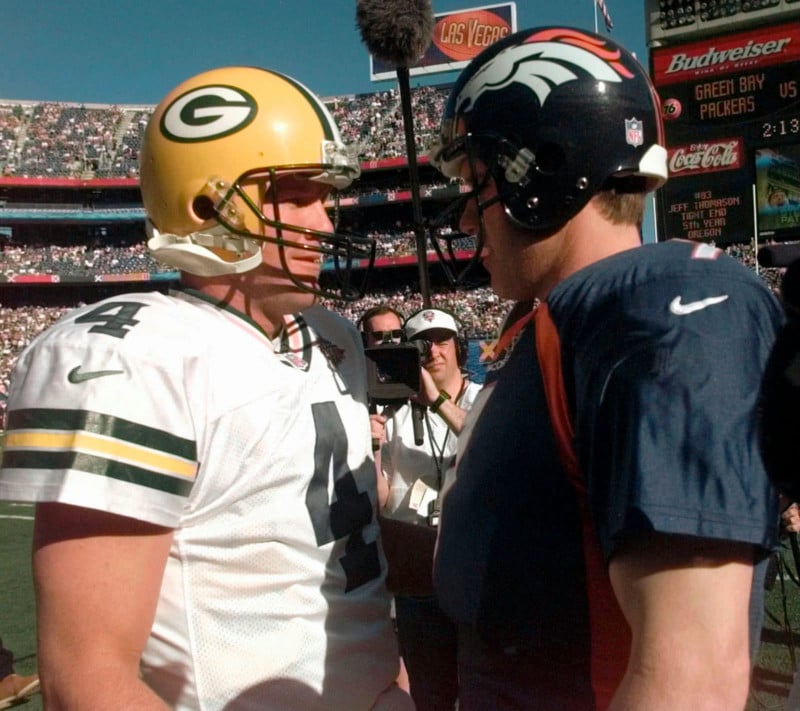

It was Sunday morning January 25th, 1998, and I was in The Associated Press’s trailer in the parking lot at Qualcomm Stadium, San Diego. Last-minute preparations were underway for coverage of Super Bowl XXXII between the Green Bay Packers and the Denver Broncos – Favre vs Elway. Perfect!

So I was a bit surprised when Jim Dietz, my technology contact at AP, asked me to make just one last minute change to PM. I laughed at him because this is definitely not standard protocol. Normally everything is all set up and locked down by Saturday, and Sunday is to just get the job done. Making a new build of PM on game day sounded crazy to me, but Jim explained why it wasn’t such a big deal, and that he had faith in me.

Back then it was important for AP to include the words “DIGITAL PHOTO” in some IPTC field (I can’t remember which one) if the photo was taken by a digital camera versus film. I frankly think it was a “be prepared” warning to AP’s members (newspapers) because the images from the 1.3MP NC2000e camera were a bit low resolution, especially when the editors did a tight crop. But since AP’s Super Bowl coverage was all digital by then, Jim asked me to just “rubber stamp” every photo that PM processed with this IPTC field indicating a digital source.

It was an easy enough fix (what we nerds call a “one-liner”), so I agreed and made a new build in the trailer on my laptop. Jim proceeded to test this build, but I had to give it a new version number and I was at 0.99. So I jokingly called it the “Elway Release” because I was rooting for Denver.

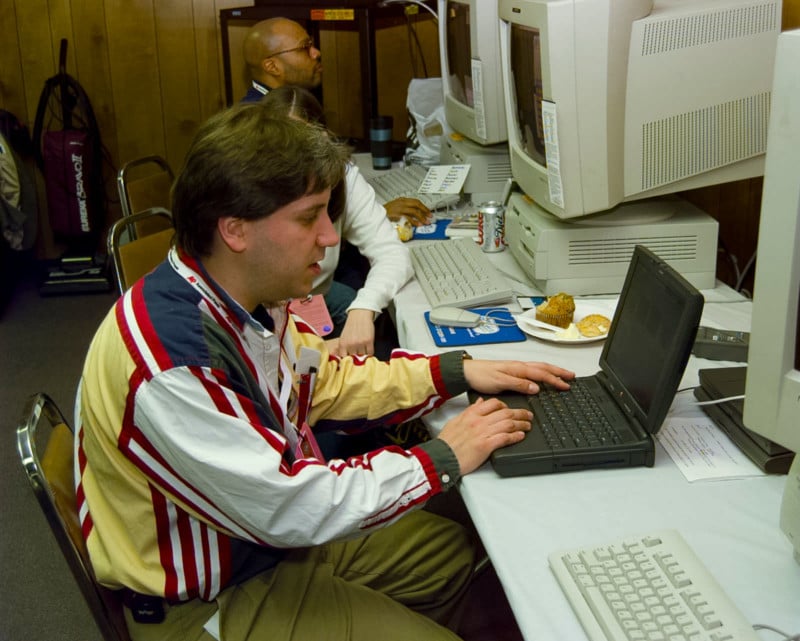

Project Manager Howard Gros was not too happy to have to install the Elway Release on all of the computers in the trailer, and especially the laptops that were ready to leave for the stadium seats and end-zone to accompany the fixed-position photographers.

Howard wasn’t upset that I called it the Elway Release (even though he was rooting for Green Bay), it was the last-minute changes. But you have to get it right, and this would eliminate the chance of any NC2000e photo slipping into the system claiming to be “film” quality. These were definitely “digital quality,” which had a bad reputation back then. Good enough for the newspaper rag apparently.

Fortunately, everything went well as far as I could tell. Photographers on the field would have their 105 MB (my guess) PCMCIA hard disks rushed very carefully to the parking lot trailer by (“film”) runners in envelopes with a pre-printed name of the photographer and their quick note of what happened (e.g. “forced fumble on 20”).

These photos would get ingested on one of the four AP “Piranha” servers (Windows NT boxes with 3 PCMCIA card readers each), the disks erased and sent back to the photographers like clockwork. And sometimes the runners would have to swap out a freshly charged camera as well because the NC2000 (and all Kodak DCS 4xx cameras) had a fixed battery.

Considering the cost of these cameras ($17,950, but discounted to $16,950 for AP members), I thought it was strange to see several just sitting on a shelf in the trailer – until I realized they were all being charged.

The Piranha servers would “ingest” the photos into folders onto the new AP Server (“Audrey”) with the last name of the photographer (e.g. “Martin”), and a unique number based on a “twin check” sticker. The twin check stickers came from a roll that had pairs of sequential 4-digit numbers that are used when developing film to maintain provenance.

I thought it was funny that AP was still using film “technology” for digital, but it was all very well organized and efficient. The notes on the envelopes would help to find high-priority moments, and the combo photographer / twin check number would give the editors the folder name (e.g. Martin-1234).

The photos from the fixed-position photographers (e.g. seated in the endzone) took a very different trip to the trailer. Their trip was relatively immediate because it was wireless and no runners were needed (other than a camera swap of course). This was a first for AP to have wireless transmission from the field.

Each photographer in the seats had a “laptop operator” sitting next to them with a Mac laptop zip-tied to an upside-down milk crate. The crate held a battery (UPS), a BreezeCOM wireless link, and radio gear for voice communication between the laptop operator and an assigned photo editor in the trailer. I recall two photo editors assigned to the four fixed photographers, each editor covering two photographers.

I know there were 6 wireless links using BreezeCOM technology (early 802.11), and the signals were bounced off repeaters from a light ring above the stadium. Howard recalls that during NFL’s “smoke test” on Saturday they discovered that AP was using the same frequency as the blimps and AP knocked out their video feed. AP changed to some Australian frequency to stop the interference. Funny now but not at the time for sure.

Although Photo Mechanic was running on these stadium seat laptops, the laptop operator was not in control of Photo Mechanic, or the actual operation of macOS for that matter. Those in control of the laptops were the editors in the trailer, using a remote control software called Timbuktu. Each of the two editors was managing three instances of Photo Mechanic: one on their own computer in the trailer, and the other two being Timbuktu views of the laptops in the stadium seats. Confused yet?

When an important event happened, or just during breaks, the photographers would eject their PCMCIA hard drive from their NC2000 camera and hand it to the laptop operator, who would radio their editor that a new disk was being mounted into the PCMCIA slot of the laptop. The editor would see this happen in their Timbuktu view of that laptop and would open up that folder in PM, then browse the photos.

When they found photos they wanted, they would copy them to a mounted folder on the desktop. This would initiate a lossless compression transfer of the RAW photo from the stadium seat laptop to the editor’s folder on their Mac in the trailer. After all desired photos were copied, the disk was remotely erased by the editor in preparation for more photos to be captured.

Then, most importantly, the editor would warn the laptop operator that the hard disk (aka a spinning magnetic platter) was about to be ejected because sometimes these disks would pop out of the laptop reader “unexpectedly” and with great intent. I have video of this behavior with my PowerBook G3 laptop (which still runs to this day). There’s no way a hard disk would survive landing on concrete stadium steps. The laptop operator (aka laptop “sitter”) would literally catch the hard disk and then carefully hand the PCMCIA disk back to the photographer. This process would merrily repeat and the result was very fast delivery of photos.

All photos selected by the photo editors using Photo Mechanic were then sent to AP Server folders for the “preppers”, aka those who manipulate pixels in Photoshop, to open and process. All the incoming Kodak DCS RAW photos were “developed” using my “DCS Photo” plug-in. This was like an early version of Adobe Camera RAW. Rather than use Kodak’s Photoshop “acquire” plug-in, photos would come into Photoshop via my “file format” plug-in that only handled “.TIF” files that were obviously Kodak DCS RAW files not normal TIFF-formatted files. The beauty of this setup was that the photo editors were freed to edit photos without “living” inside of Photoshop (and Kodak’s plug-in).

Only the “preppers” needed to use Photoshop in order to manipulate pixels and recover an image as best they could due to the fact that these were digital photos. A big part of this “digital restoration” was the use of Quantum Mechanic, my Photoshop noise filter plug-in that greatly reduced high ISO noise. AP actually used a “simplified” version of this filter called AP Filter that only had low, medium, and high settings to choose from. Two years earlier at Super Bowl XXX, AP used a prototype noise filter I made called ColorClean.

After this big game and seeing Photo Mechanic get put to a real test with no problems, I decided to release Photo Mechanic the next week (version 1.0.1 was available for download on February 4th, 1998). The Associated Press distributed Photo Mechanic as AP Viewer for a few years along with AP Filter.

I thought The Associated Press’ setup was impressive but I was just a “photo nerd” software developer – who was I to know how big this event was for AP and digital photography? I really felt like I was a fly on the wall, unknowing I would become a fly in the ointment. This was AP’s first wireless transmission from the field for a Super Bowl, the first time computers in the trailer were even connected by ethernet. The first all-digital Super Bowl coverage for AP was XXX in Tempe two years earlier (which I witnessed and contributed to).

I didn’t work for AP like everyone thought I did. But I took some pride in knowing that all those photos were “seen and developed” by Photo Mechanic before being distributed worldwide by AP. I didn’t imagine it would be the first of 25 years for Photo Mechanic to be a central part of sports photography history. I like to joke that Tom Brady has been to 10 Super Bowls but Photo Mechanic has been to the last 25 of them.

As this was the process 25 years ago, you can imagine how much that has changed. I believe The Associated Press had a large advantage over their competition back then due to the fact they were the distributor of the NC2000 camera. Despite their expense, the ROI on this expensive camera was very quick, and that is why the Vancouver Sun and sister Calgary Herald were smart to be the first all-in newspaper adopters of digital in North America. The Rochester Democrat and Chronicle in Kodak-land followed soon afterward but not because the photo department was eager to go digital – it was a decision made by management.

I would like to thank Brian Horton and Howard Gros for sharing their memories of that day. Thank you to Nick Didlick (then from Vancouver Sun), and Rob Galbraith (then from Calgary Herald) for helping to herald in this new digital era and for providing endless supportive ideas. Special thanks to the late Jim Dietz who worked with me to integrate PM into AP, and to the late Dave Martin who embodied the spirit of photojournalism and inspired me and many others. Both Dave and Jim gave their lives to the pressures of covering big sporting events – I miss them both dearly. I also wish to express my deep thanks to The Associated Press for placing trust in such a small company as myself, and for agreeing to sell Photo Mechanic as AP Viewer.

This was the Super Day that kicked off my career, and the game ain’t over yet!

About the author: Dennis Walker is the founder of Camera Bits, the company behind Photo Mechanic, a popular front-end photo ingesting, tagging, and browsing tool used by photographers around the world. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was also published here.

Credits: Photo captions by Brian Horton and Dennis Walker, unless otherwise noted.