Planetary ‘Photobombers’ Complicate the Search for Another Earth

![]()

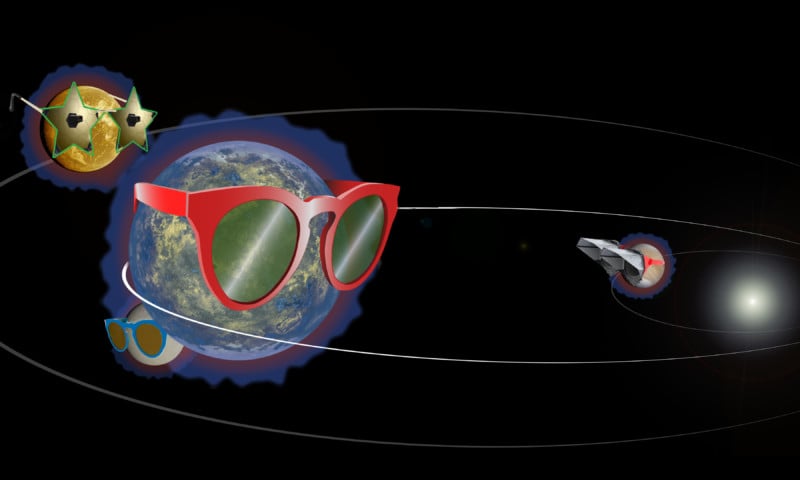

Scientists say that their attempts to find exoplanets that could host life — basically, another Earth — could be obscured by what they refer to as planetary “photobombers,” which could dramatically alter results.

According to a new NASA study, scientists believe that their efforts to search for habitable exoplanets is being inhibited by the light case by other planets in the same star system. These “photobombers” is inhibiting even the most advanced space telescopes’ ability to properly search for habitable planets, and scientists are looking into ways to overcome this problem.

“If you looked at Earth sitting next to Mars or Venus from a distant vantage point, then depending on when you observed them, you might think they’re both the same object,” explains Dr. Prabal Saxena, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

“For example, depending on the observation, an exo-Earth could be hiding in [light from] what we mistakenly believe is a large exo-Venus.”

Saxena led a research project, which was published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters earlier this month, which modeled how this “photobombing” effect would impact their ability to observe exoplanets and suggests ways to overcome the issue.

NASA explains that astronomers use telescopes to analyze light from distant worlds in order to see if they could support life. But as big as the universe is, it’s also very crowded: within a 30-light-year distance of Earth, there are about 30 stars that are similar to the Sun that house planets that could support life.

Given the distances that are being discussed, light diffraction could likely cause two exoplanets to visually merge with each other from the vantage point of telescopes that are used to observe them. As Space explains, this can cause some issues with analyzing the data from these observations as cross-contamination of two objects can significantly confuse the results.

“This photobombing phenomenon, in which observations of one planet are contaminated by light from other planets in a system, stems from the ‘point-spread function’ (PSF) of the target planet,” NASA says. “The size of the PSF of an object depends on the size of the telescope aperture (the light-collecting area) and wavelength at which the observation is taken. For worlds around a distant star, a PSF may resolve in such a way that two nearby planets or a planet and a moon could seem to morph into one.”

If this happens, data that scientists gather could be skewed significantly and it is very possible that a habitable world would not appear as such because of the cross-contamination. Saxena looked at a situation where scientists might use a telescope recommended in the 2020 Astrophysical Decadal Survey to look at Earth from 30 light-years away.

“We found that such a telescope would sometimes see potential exo-Earths beyond 30 light-years distance blended with additional planets in their systems, including those that are outside of the habitable zone, for a range of different wavelengths of interest,” Saxena says.

The study suggests a few ways to deal with this “photobombing” problem, including developing new methods of data processing, studying systems over time in the hope that the planets that would interfere with each other would move enough to be visible across multiple studies, or even increasing the size of a telescope to reduce the effect.

For now, no single solution was determined, but at least scientists are aware of the issue and can take it into consideration in the future.

Image credits: Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, an Earth-size exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star in the constellation Cygnus, by NASA/Tim Pyle