I Was One of the Lucky Few to Win an Epson R-D1s Digital Rangefinder

![]()

In 2010, when I started working as a journalist in Tokyo, layoffs of newspaper photographers had reached the stage where reporters couldn’t expect a decent layout unless they provided their own story art. I couldn’t afford a camera, but I also couldn’t afford to see my stories published without illustration, so I bought a DSLR and soon learned to hate it, or at least to hate the self-conscious way it made the people I was photographing behave.

Editor’s Note: Author and journalist Dreux Richard reported on immigration in Tokyo for eleven years. He reflects on the photographs he took, the Epson R-D1 he used, and his thoughts on receiving a new R-D1s from Epson last month after the company found 30 in a warehouse.

A Camera People Wouldn’t Notice

Every day when I walked to work, I passed a used camera store, of a type you can imagine if you’ve ever had romantic notions about the camera stores of Tokyo. It was a dusty warren of old lenses and darkroom equipment, inhabited by an aging hippie in a grease-stained canvas smock. I met him for the first time when I offered to let him name his price for my DSLR, then asked to buy “a camera that people won’t notice too much.”

He sold me an Epson R-D1, which he thought I’d like. He also had a good, long laugh at what I was asking for: an invisible camera? A camera implanted in my eyeball? The difference between using a bulky DSLR and a small rangefinder, he pointed out, wouldn’t be as dramatic as I hoped.

He was right. At work, I covered Japan’s growing West African communities, which required me to spend my nights in Tokyo’s red-light districts. Some people I wrote about had turned to crime after discovering how difficult it was for immigrants to find jobs in Tokyo. Others were earning honest paychecks. But nearly everyone, whether or not they were involved in illicit work, was uncomfortable being photographed. For years, the organized crime unit of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department had treated the city’s Nigerian community as if it were a criminal entity, harassing innocent people for rumors about their acquaintances.

This wasn’t a history that a discreet camera could solve, so I learned to document the visual nuances of these communities in other ways—in other settings, that is. During my frequent trips to Nigeria, I photographed the homes, families and children of the men I knew in Japan, things they were proud of and felt secure about.

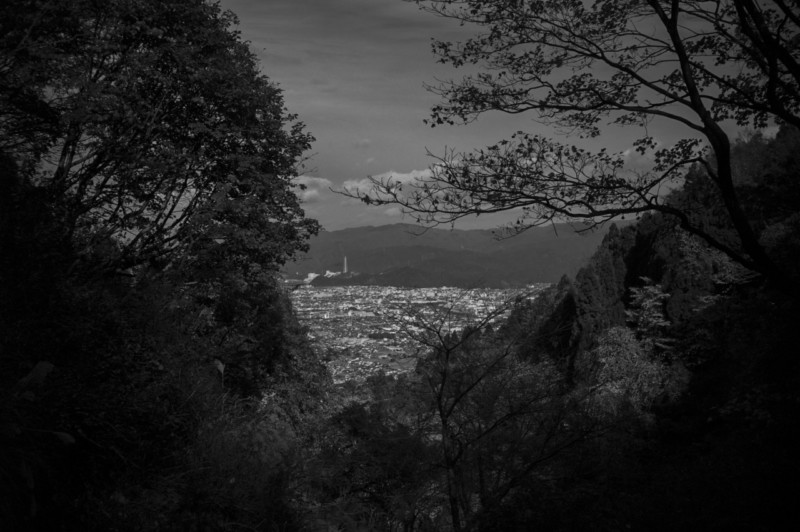

These photographs led me to understand the special quality of the camera I was using. Raising a camera to my eye—any camera—inevitably distracted the people I was observing. But not all cameras distracted me. Because the R-D1’s viewfinder didn’t widen or magnify my viewing perspective, using the camera didn’t remove me from the moment, not nearly to the extent that a DSLR prism or electronic viewfinder would have. I shot using a 40mm-equivalent lens, to match the 1:1 perspective of the R-D1, and found that I was rarely ever surprised by a photo I took when I reviewed it later. I always remembered what I’d seen, even though the camera had separated me from it.

I recognize this quality when I revisit the photos I took with the R-D1. I see it in the photo I chose to exhibit at Epson’s gallery last month, of a friend’s daughter sitting in his chair, waiting out the last few days before his return to Nigeria—his first visit home in over a year.

I recognize it in a photo of my wife, taken after she recovered from a near-fatal car accident, as she became reacquainted with living at home.

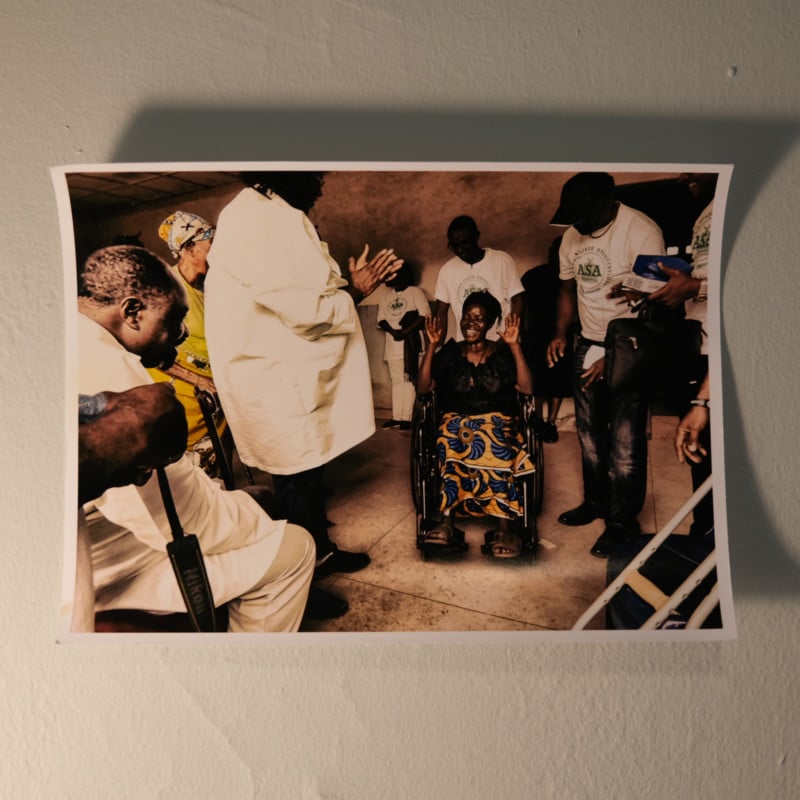

I recognize it in a photo I keep on the wall of my office, of a disabled woman in rural Nigeria receiving a wheelchair during a fundraising event. Her family contacted me after her death, through a Nigerian civic organization in Japan, to express how important it was that someone had captured, “one of the last joyful experiences of her life.”

The moments in these photos don’t feel as if they were severed from the flow of events that came before and after. They feel like moments that were consciously elongated, in response to the desire to linger in periods of anticipation and possibility.

Made to Meaningfully Experience the World

They’re photos from particular types of experiences, taken by a person who was drawn to them. But they’re also photos from a particular kind of camera, one that softened the boundary between experiencing the world and taking a picture of it. I’m not aware of any other camera that allows its users to view the world through a flat piece of glass, rather than through a lens or an electronic screen. It’s a small distinction, but one that strikes me as increasingly meaningful.

It’s my impression that Epson sees these cameras as historical objects. I never developed that specific feeling of reverence toward my camera. It was purchased cheaply, at a time when the online collecting market hadn’t consumed all the rangefinder cameras in the world. I intend to treat my new camera in the way I was advised by that second-hand camera salesman in Tokyo twelve years ago.

“The most natural photos come from a little impatience,” he said. “As if you wish it were not necessary to take pictures at all.”

About the author: For six years, Dreux Richard covered Japan’s African communities for a daily newspaper in Tokyo. His first book, Every Human Intention: Japan in the New Century, was published by Pantheon in 2021. It is available wherever books are sold. Watch his video portraits of West African immigrants living in Japan: here, here, and here.