Spirit Photography Captured Love, Loss, and Longing

![]()

Photography has always had a relationship to haunting as it shows not what is, but what once was.

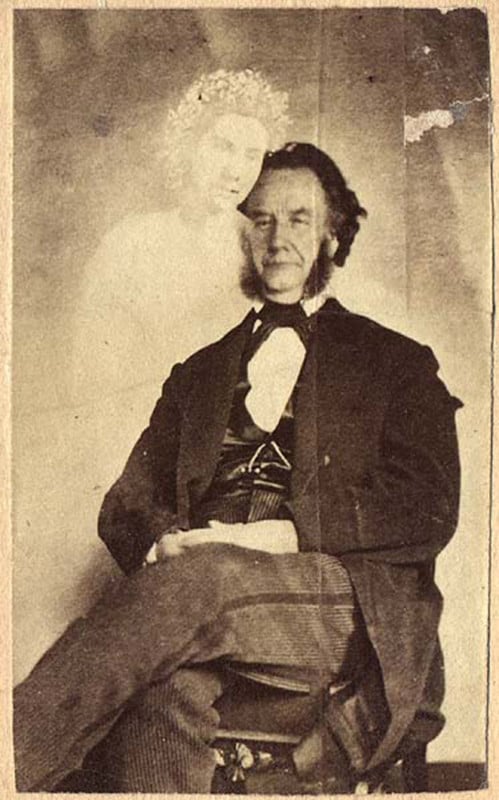

This association is exaggerated by spirit photography, which are portraits that visually reunite the bereaved with their loved ones — a phenomenon I attribute to the creative innovation of a Boston woman in 1861.

Modern readers may be preoccupied by the motives and methods of spirit photographers — their use of double exposure, combination printing or contemporary digital manipulation to produce semi-translucent “apparitions.” But far more interesting is the impact the resulting photographs had on the bereaved who commissioned the portraits. At heart, the Victorian interest in spirit photography is a tale of love, loss and longing.

Spirit of the Age

Spirit photography developed within the context of spiritualism, a 19th-century religious movement. Spiritualists believed in the soul’s persistence after death and of the potential for continued bonds and communication between the dead and the living.

In 1848, when two young women of Hydesville, N.Y., claimed the ability to hear and interpret the knocking of a deceased peddler in their home, spiritualist ideas were already in the air.

Some 19th-century spiritualist artists saw their work as being inspired by an unseen presence. For example, British artist and medium Georgianna Houghton produced abstract watercolours she dubbed her “spirit drawings.” Similarly, about 20 years after photography as a medium emerged, spirit photographers began attributing their work to an external force, a presence that temporarily overcame or possessed them. The spiritual “extra” that appeared alongside the bereaved in spirit photographs — sometimes clearly a face, at other times a shape or object — was meant to be understood as not having been made by humans.

Paired with the longing of the bereaved, spirit photographs had the potential to become intensely personal, enchanted memory objects.

Sustained Bonds

Unlike postmortem photography — the 19th-century practice of photographing the deceased, typically as though sleeping — spirit photographs did not lock the loved one in a moment after separation has occurred through death. Instead, they suggested a moment beyond death and therefore the potential for future moments shared.

Spirit photography encouraged and then mediated the resurgence of the deceased’s animated likeness. At a time when many available technologies — such as the telegraph, telephone and typewriter — were being applied towards communication with the dead, spirit photography offered a visual record of communication.

But in spirit photographs, the beloved seldom appeared at full opacity. Using the technique of semi-translucence, spirit photographers depict spirits as animated and “still with us.” That they are only half there is also indicated. In this way, spirit photographs illustrate the lingering presence of the absent loved one, just as it is felt by the bereaved.

Spirit photographs were not the first photographs to depict ghostly apparitions. But they do mark the first instance wherein these semi-translucent “extras” were marketed as evidence of continued connection to the deceased.

As a service rendered within the bereavement industry, spirit photographs were meant to be understood as the grief of separation, captured by the camera — and not constructed through some form of trickery.

Spirits in the World

Belief in the appearance of miraculous impressions of forms and faces may appear novel in the emerging medium and technology of photography. But a longer tradition of finding meaning and solace in the apparition of faces can be seen in Christian traditions of venerating relics such as The Veil of Veronica which, according to Catholic popular belief and legend, bears the likeness of Christ’s face imprinted on it before his crucifixion.

Even in the 19th century, recognition of the beloved in spirit photographs was occasionally equated with pareidolia — the powerful human tendency to perceive patterns, objects or faces, such as in relics or random objects.

In 1863, physician and poet O.W. Holmes noted in Atlantic Monthly that for the bereaved who commissioned spirit photography, what the resulting photograph showed was inconsequential:

It is enough for the poor mother, whose eyes are blinded with tears, that she sees a print of drapery like an infant’s dress, and a rounded something, like a foggy dumpling, which will stand for a face: she accepts the spirit-portrait as a revelation from the world of shadows.

If the photographer’s methods were exposed, the bereaved still maintained their spirit photograph was authentic. The ambiguity of the figures that appeared seldom deterred the bereaved from seeing what they hoped for. Indeed, it was this very leap of faith that incited the imaginative input required to transform these otherwise unbelievable photographs into potent and intensely personal objects.

In 1962, a woman who had commissioned a photograph of her late husband shared with the spirit photographer: “It is recognized by all that have seen it, who knew him when upon Earth, as a perfect likeness, and I am myself satisfied, that his spirit was present, although invisible to mortals.”

Haunting Refrains

Spirit photographs were often proven to have been produced through double exposure or by way of combination printing. Thus, it would have been equally possible to produce photographs wherein the deceased appeared at full opacity alongside the bereaved — seamlessly reunited. And yet the tendency to present the absent individual at a lesser opacity has persisted — even within contemporary, digitally produced composite portraits.

The use of semi-translucence in depicting the remembered individual, is a deliberate indication of a presence that is felt but not seen, except by those attuned to it.

While spirit photographs were cherished as messages of love from beyond the grave, surely they were also messages of love to the departed.

About the author: Felicity T. C. Hamer is a PhD Candidate and Public Scholar in Communication Studies at Concordia University. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. This article was originally published at The Conversation and is being republished under a Creative Commons license.