Photographing the Demise of Martin Tower

![]()

For those not from a certain area of Pennsylvania, you likely have never heard of Martin Tower or knew that it was imploded in a spectacular way earlier this year. But for those in the Lehigh Valley, the third-largest metropolitan area in PA, Martin Tower served as a symbol of many meanings, from the fall of one of the greatest steel companies in the world to a landmark whose relief stood out in stark contrast to the surrounding landscape.

The 332’ building, shaped in a unique cruciform configuration, once housed the headquarters for Bethlehem Steel, once the second-largest steelmaker in the world. While dwarfed by the likes of the U.S. Steel Tower in Pittsburgh and many other buildings both there and in Philadelphia, Martin Tower was the largest building in the Lehigh Valley and was visible from miles away across the area. The groundbreaking to construct the tower was in 1969 and by 1972 the building was completed and occupied. Named after Bethlehem Steel’s former chairman Edmund F. Martin, the building utilized 32 million pounds of steel and housed nearly 1,200 employees across several different departments. Reams have been written and college courses taught about the downfall of Bethlehem Steel, and to this day the answer to the question of “why did Bethlehem Steel go bankrupt?” will be dependent on who you’re asking.

While Bethlehem Steel fully went bankrupt in 2001 and the last steel employees left the tower in 2003, a few companies retained residency in the tower until 2007, when it became fully vacant. A testament to its notability, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010 and efforts to save it continued up until its demolition.

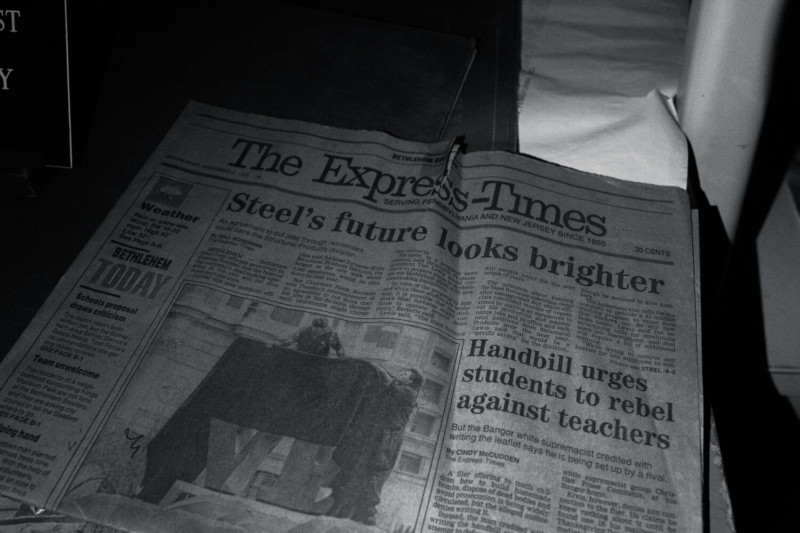

My fascination with Martin Tower began several years ago when I became enamored with combining a budding interest in urban exploration with my already solidified bug for photography. The building, being the largest in the area was a constant muse and appeared in my work several times whether by intention or happenstance. Luckily, in 2014, the owners and the site manager allowed for a day of public exploration of the first floor of the tower and the grounds around it, which housed a variety of annex buildings including a power house and a print shop. The building itself was still immaculate, from the Mad Men-esque wallpaper in the women’s bathrooms to the computers and notepads still left at the front desk reminding me more of a time capsule than a building that had been abandoned for seven years.

Martin Tower Instameet, 2014

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This limited visit at the Instameet only solidified my interest in fully exploring every nook and cranny of the tower and I spent the next several years on and off writing and calling the owners and property management trying to obtain access to document the inside. That came in a roundabout way, after I started working at the National Museum of Industrial History (NMIH) in Bethlehem, just three miles from the tower’s site and on the scenic campus of the former steel mill.

The museum houses a significant archive of Bethlehem Steel materials, including 35mm, medium format, and large format negatives that were shot throughout the company’s history. With these stunning images, many of which likely haven’t seen the light of day since they were developed, the museum held several events where the public was able to see the building come to life through the lenses of company photographers in black and white and color film.

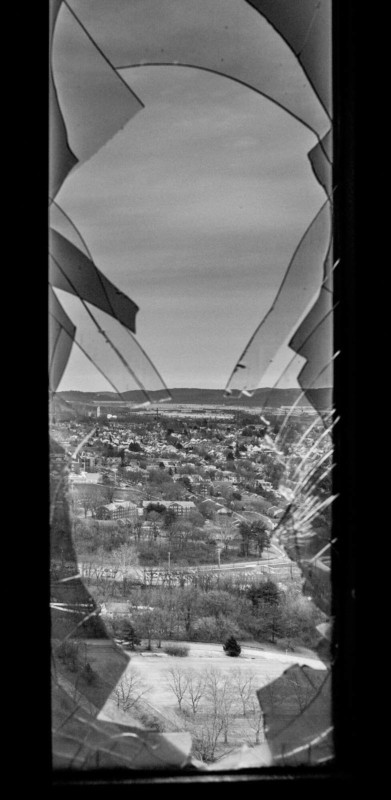

Through my work with the museum I was able to visit the tower several times, once in 2017 as mosaics from the former printery building were removed prior to its razing, and several more times earlier this year as the building was being prepared for demolition and museum volunteers were removing paperwork and artifacts left in the building. While the building was unfortunately gutted before we were able to visit, I was able to photograph the entire site as well as much of the building’s first floor, basement and sub-basement, and the unparalleled view from its rooftop.

A 2017 Visit to the Tower

In 2017 the printery is razed and work began on the other annex buildings in the tower. These views show the printery building being demolished and a view of a patrol office inside the main tower.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A Final Look: Inside the Last Days of Martin Tower

These images, taken in March of 2019, provide a final look documenting the inside of the building prior to its preparation for implosion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A Week Prior to the Implosion, May 2019

As the building’s implosion drew nearer, I was intent on locating a unique view to witness this historic event. Thousands of onlookers would be inundating every public viewing area around town, so my first inclination was to try to get a helicopter for the day. I assumed this wouldn’t be an easy feat, but a friend of a friend, Ted Rosenberger of Vertivue Air Charters quickly agreed to turn down paying customers that day to fly me and document the implosion for NMIH archives. Prior to the implosion day, we took a test run – seeing where the no-fly zone was and where we ideally would like to be for the actual demolition. With us was Gardner Raymond of Consequence Video Designs, who operated the helicopter’s nosecam and provided the local news station, WFMZ, with live footage and NMIH with the video for its archives. Both have my eternal thanks for providing not only the museum with an amazing video but also giving me a platform to witness history and photograph one of the most memorable days I’ve had in some time.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Implosion, May 19, 7:03AM

The building, which took three years and an unbelievable amount of steel and concrete to construct, came tumbling down in 16 seconds. If you’ve never seen a large building implode, especially one that holds a sentimental place in many people’s lives, it’s both shocking and stunning. From the air, it almost looked like a video game, and it wasn’t until we were back on the ground and friends were sending me their videos that it began to look real. Following the implosion, we circled the site until the dust cleared to get some footage for the news station and so I could get some shots of the rubble before we headed back to the airport. I went over to the site later in the day to get some shots of the rubble and was able to return the next day and get access to the site to take some closer photos. The demolition team did an astounding job, with nearly all of the rubble falling in on the building itself and minimal debris surrounding the site.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The Aftermath

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Work at the implosion site is still ongoing and crews are still working to remove, sort, and process the I-beams, concrete, and other rubble from the implosion.

I also want to thank all of the workers and site management personnel who escorted me around the tower and gave me ample time to work, as well as my team at NMIH who let me spend time working on this project.

For those wondering about gear, I was shooting with two Canon 5D Mark IIIs, one outfitted with a Sigma 120-300mm f/2.8 and the other with a Sigma 50mm ART f/1.4. Figuring out which focal length to use was tricky. In hindsight, I wish I would have shot the actual implosion with the longer lens, but a delay in the implosion coupled with a very short notice before the explosives went off meant I was shooting with the 50mm to ensure I was getting the full implosion. There were many others who got equally good, if not better, shots from the ground, but I was satisfied with my work due to the unique angle.

About the author: Glenn Koehler is a photographer and writer based in the Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Koehler’s work spans photojournalism during fires and Hurricane Katrina to fine art displayed in galleries and museums. He is currently working towards an A.S. at Northampton Community College and plans to continue his studies at Moravian College. His work has been featured in regional publications such as The Morning Call and in national publications such as The Washington Post and the Associated Press. You can find more of his work on his website. This article was also published here.