Gordon Parks, Flavio, and Me: The Evolution of a Photo Story

![]()

Do you ever wonder why one person gets chosen over another, or how a story comes to be told in a certain way? Well here’s something that happened to me recently that gave me new insights about how choices are sometimes made and what it tells us about the people who make them.

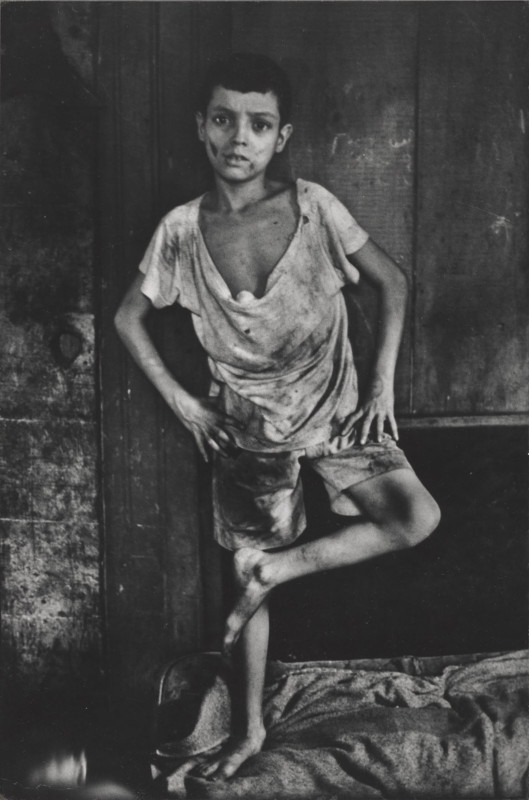

Through the Life office in Rio, Parks was connected to a family, and he began working on the story. But the more he shot, the more he found himself concentrating on a different family member, a young boy named Flavio, the eldest of eight children. Flavio, then twelve, was painfully thin and suffered from severe asthma, but something in him connected with Parks and Parks began to concentrate his pictures heavily on the boy.

When the Life office heard about it, they tried to get the story back on track. But Parks worked hard to convince them that he was right to concentrate on Flavio, and ultimately they agreed. For twenty days, he focused his camera on the boy, and in the end, he brought home a rich trove of beautifully humanistic images that showed the poverty of the Favelas but also the humanity there.

The story was published in June of 1961, a 12-page spread that became a subject of conversation across America, while Flavio became a touchstone for millions. Life magazine brought him to the states, where he received medical treatment for his asthma, then lived with a family in Colorado for two years. He learned to speak and read English and saw life as an American for that time, but then he was returned to Brazil against his wishes, and he lived his life there, never returning to America… until this year.

The story follows several threads from there. The Brazilian press was incensed, convinced that Brazil had been unfairly singled out for its poor. O Cruzeiro, a popular Brazilian publication sent Henri Ballot, one of their staff photographers to New York to find and shoot a story about a poor child living in the slums of the Lower East Side. Of course, he did.

The pictures of poverty he made in NY were published on his return, and they sparked a lot of heated conversation, not unlike the photographs of Baltimore we are seeing right now.

Eventually, that story died down, but the story of Flavio continued to be told. Over the years, Parks occasionally visited him and took pictures, and others contributed to the story as well. Many of these pictures have now become part of a show called Gordon Parks: The Flavio Story, which is currently at the Getty Center. They can also be seen in the book The Flavio Story. The Getty, working with the Ryerson Image Center of Toronto, Canada, and Instituto Moreira Salles of Brazil, crafted a show that offers a rich collection of images which bring this complicated story to life.

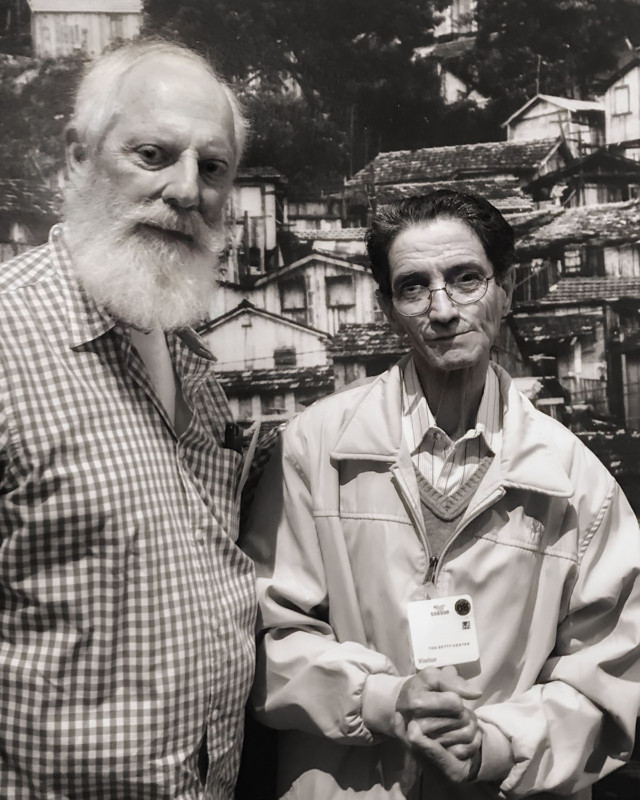

I was invited to the curatorial walkthrough, and one of the highlights was that Flavio would be present, his first visit to America since 1962. I was curious about him, what the long-ago exposure had done to him, and what his take on the story would be. The tour began with introductions by the curator, after which Flavio spoke briefly, welcoming everyone. Then we walked through the rooms of the exhibition to listen and learn about the pictures and the stories behind them.

I was walking in pain, an extruded disc sending fire down my leg. When it got to be too much, I slipped away from the group and found a bench in the next room to rest on. I sat there listening to scraps of the curator’s talk floating into the room, my head down. And then I heard a voice say, “Are you ok, you look like you are in pain.” It was Flavio! He had noticed me hurting and walked away from the group to make sure I was ok. And at that moment I understood why Gordon Parks had pushed Life magazine to let him tell Flavio’s story all those years ago.

This was Flavio’s big day, his first time back in America in fifty years, his chance to be seen and to tell his story, and instead of focusing on that he had walked away to offer comfort to another human being. In that instant, I saw the quality that made Flavio special and knew that quality was what Parks had seen as well.

I hope you get to see this show or read the book. Gordon Parks’ photos are warm and wonderful, and seeing his pictures next to the more pointed work of Henri Ballot lets you experience how differently two people can approach the same story. Both men tell their version, but the difference between Parks’ pictures, made to show the suffering of the poor in hopes of making a difference, and Ballot’s made to only prove poverty exists everywhere result in pictures which stir very different feelings. I know which ones I like.

Regardless though, don’t miss the pictures of Flavio. See what a special human being looks like, even at twelve.

About the author: Andy Romanoff is a writer, photographer, photojournalist, and a few other things besides. The opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author. To see or read more of Andy’s work, visit his website or give him a follow on Instagram and Medium. This piece was also published here.