Photographer Exposed for Using Film Set Shots as ‘Documentary’ Photos

![]()

When Mehrdad Oskouei, a well known Iranian filmmaker, was planning to produce his last film Starless Dreams he asked one of his former students, Sadegh Souri, a photographer and a cinematographer to join his crew as a camera operator.

It took Oskouei over six months to work through the bureaucracy of the Islamic Republic and obtain a rare permit with extraordinary access to make the film at the all-female facility. He attributes the permit to his previous two films in the same genre, and his long relationship with the authorities who had granted past access.

Three days into filming, Oskouei realized that Souri may not have had the technical competence to execute his project. “I wanted to create a cinematic vision with shallow depth of field, but Souri’s skills are suitable for other types of production,” he says.

Instead of firing Souri, Oskouei allowed him to stay on and work as a behind-the-scenes and crew photographer. Souri had traveled to Tehran from Zahedan, a southern city over 15 hours of drive from the capital, to work on the film. The director felt that this would be a fair resolution for his former student. However, seven days later Souri left the production for another project.

As Oskouei completed his film and entered it into international festivals, Souri wrapped his photo essay Waiting Girls (Persian: دختران انتظار), a series of black and white images from the correctional facility. In all international publications and contests, Souri’s photo series has a more provocative title, Waiting for Capital Punishment. Souri never informed the director nor asked for his permission to publish his pictures.

A recent article published in Akkasee, a photography magazine in Iran, reveals Souri’s unethical practices and questions his access to his subjects among other concerns. The article is authored by Farhad Motaee, a photography master student and a photography teacher. Motaee first came across Souri’s pictures during a workshop in the summer of 2017. Shortly after he connected Souri’s images to Starless Dreams, and discovered that some of the photos were exact copies of Oskouei’s film.

When I spoke to Souri over the phone, he criticised Motaee and his motivations, and refused to answer any questions directly. “I know for sure that Mr. Motaee is doing this because of other people who are jealous of my work,” says Souri. When pressed about this accusations, he didn’t provide anything to substantiate his claims. He feels that he is being victimized by those who are envious of his success.

False Narrative – Captions and Statements

Souri’s narrative in Waiting for Capital Punishment differs with the girl’s own words in Oskouei’s film. When I questioned Souri about the provocative title of his photo essay, he claims that someone at The Guardian newspaper made that up for an article. The Guardian published his photo essay with the headline “Waiting to die: the Iranian child inmates facing execution” in January of 2016. Clearly Souri had provided the information to the newspaper and never tried to correct the headline if he felt it was misleading. The Guardian article is one of many articles with the same title.

Souri’s captions and statements suggest that the girls are waiting for their final sentencing and capital punishment, but the movie is shot in a correctional and rehabilitation center (Persian: کانون اصلاح و تربیت ). The film shows that the girls live in a dormitory, with daily activities and classes, and access to an enclosed yard.

Souri insists that some of the girls could still face capital punishment even at this center. Conceivably, this is the narrative that he would like you to believe. However, the Iranian judicial system is based on the Islamic Sharia law, with convoluted nuances where a victim’s family can override or change the court’s sentencing in cases of capital crime. This Sharia system is fused into a set of legal codes, that require Islamic law and civil law experts to discern.

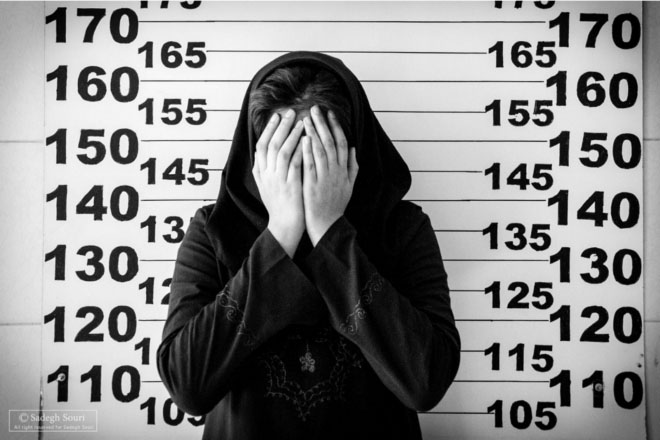

Souri’s opening photo is the portrait of a girl covering her face standing in front of a height chart. His caption reads “Mahsa is 17. She fell in love with a boy and intended to marry him, but her father was against the marriage. One day she had an argument with her father, got angry, and killed him with a kitchen knife. Mahsa’s brothers are requesting the death penalty for her.”

In various interviews, Souri explains that Mahsa initially did not give permission to be photographed, but after three days, she allowed him to make this picture. He explains that Mahsa began crying while telling her story, and as she covered her face, he made the picture. Oskouei firmly asserts that Souri’s story is made up.

According to the director, the girl in the picture is not Mahsa. Her name is Khatereh, and Souri’s caption about Mahsa is not even factual. There is a girl name Mahsa, but “she didn’t kill her father because he wouldn’t give consent to marriage” stresses Oskouei and continues “… she was never sentenced to death penalty either.” Oskouei explains that Mahsa was not present when they shot this scene. They had asked Khatereh to stand in front of the chart for a sequence that was planned in pre-production. “The caption of this photo is the figment of Souri’s imagination” says Oskouei.

Oskouei points out that the crew was always accompanied by a government minder during the entire production. Aside from the director, the authorities did not allow any individuals on the crew to speak directly with the girls.

This is not the first time that Souri has worked on a film as a cinematographer and copied the film idea and storyline almost frame by frame — some with false or entirely made up captions. Several other Iranian filmmakers have come forward with identical grievances.

Director: Mohammad-Amin Shahnavazi — Film: “Fuel Smuggler”

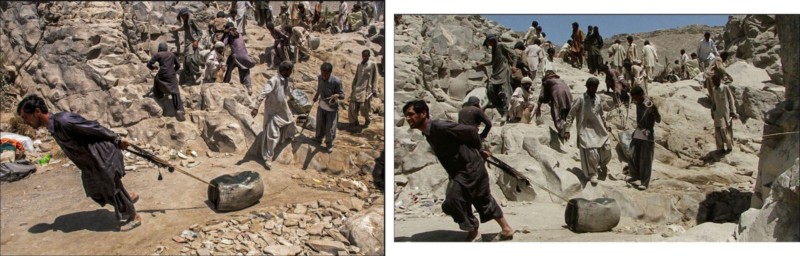

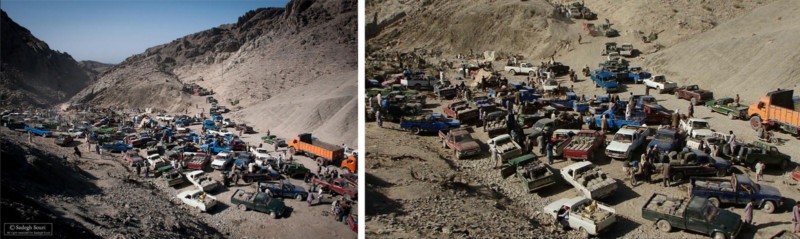

Four years ago, Mohammad-Amin Shahnavazi, a filmmaker from Zahedan, began working on a project about smugglers in his home province of Sistan and Baluchestan. Souri worked as a cinematographer for Shahnavazi for five days, and took photographs between the takes, and sometimes even during the takes. Taking photos during the takes aggravated the director as the sound of the camera shutter was being picked up on the film’s audio. Shahnavazi’s film Fuel Smuggler is yet to be completed.

Shortly after they concluded production, Souri produced a photo essay with virtually the same title, Fuel Smuggling, and presented it to international publications and photo contests. Similar to Oskouei’s film, there are exact frames from both Souri’s photos and Shahnavazi’s film.

Shahnavazi complains that he never received any of the photographs that Souri took during the filming. The director had hired Souri as a cinematographer, but when Souri began taking pictures, he promised Shahnavazi that he will be able to use them as well.

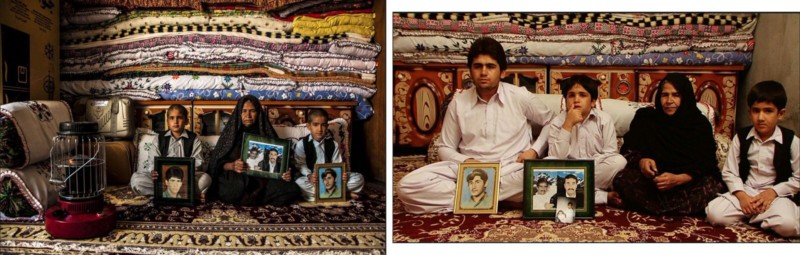

Shahnavazi gripes about one of Souri’s captions as entirely made up. The caption for the picture below reads “Maryam lost her husband and two sons in the fuel smuggling. Her husband was carrying more than 1,800 liters of diesel to Pakistan border when the police shot him to death…”

According to Shahnavazi, the main subject’s name is not Maryam, but Zarkhaton Kourdi-Tamadani. She is the grandmother of the two boys by her sides, and her son (not her husband) was killed in a car accident. “The family’s story is very intriguing, I am surprised that Souri has tried to make it more dramatic by making up such lies,” says Shahnavazi.

Souri goes as far as recreating the above scene after the production was completed earlier, without the director’s knowledge. In the photo, you can see that the two younger boys have normal length haircut during the filming, but when Souri photographed them months later, the boys have the required buzz cut for their school.

The film takes place in a turbulent area of the region, where smugglers with connections to tribal cartels and extremist Sunni groups, transport everything from fuel and drugs to electronic goods. The publication of the photos has complicated Shamnavazi’s relationship with his subjects, some of whom are his own relatives. “Souri ruined my film and his reputation” reads a quotation by Shamnavazi in an article in Nooriato, a photography magazine.

Director: Mohammad-Sadegh Dehghani — Film: “Companion”

Iranian film director, Mohammad-Sadegh Dehghani, had hired Souri for several of his projects as a cinematographer. When Dehghani was commissioned to make a film for a non-profit foundation in Iran called Hamdam, he asked Souri to join his crew as a cinematographer. The foundation works with mentally ill girls and the film showcases their accomplishments. The film is titled Companion.

Dehghani considers Souri a friend and until recently he had remained silent, but as more filmmakers have come forward he has been speaking up. In an interview with the Iranian Students News Agency (ISNA), Dehghani laments that Souri should have asked for permission before distributing any photographs. Given the vulnerability of the mentally ill girls, Dehghani wanted to give his subjects the sensitivity they deserve. The director feels that Souri’s behavior has betrayed his subjects for personal gain.

Since the film was done on a pro bono basis for a foundation, Dehghani wishes that everything about the project had been worked out in the same spirit. He emphasis that on his films, the director has the ultimate say on every aspect of production, including use and distribution of photography.

Director: Mohammad-Ali Hashemizadeh — Film: “Ak Ap As”

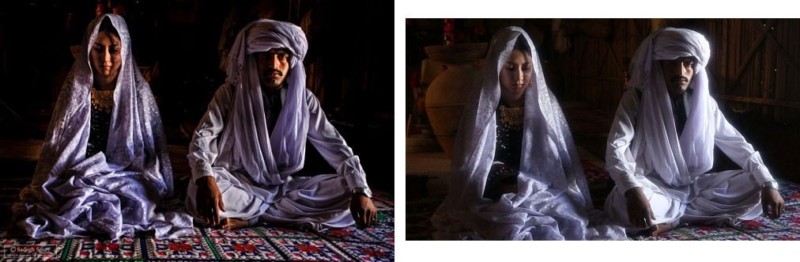

Souri worked on another documentary project in Sistan and Baluchestan province, under the director Mohammad-Ali Hashemizadeh. The film Ak Ap As is spoken in Baluchi dialect with Persian subtitle. It is an ethnographic story about the tribal traditions in the southeastern region of Iran. The title translates to soil, water, and fire (Baluchi: آک، آپ، آس – Persian خاک، آب، آتش). From his time working on Hashemizadeh’s film, Souri created his own photo story titled Wedding in Baluchestan.

In his statements and interviews, Souri does not acknowledge the films nor the directors whose stories, research, access, and frames he has reproduced. In one interview he passively explains “alongside of a film crew I gained access to the subjects…,” suggesting his independence from the directors. When I tried to quiz Souri about Oskouei’s film, and the identical frames, he pushed back by saying “I did Mr. Oskouei a favor by giving him some of my photographs.”

The documentation against Souri is overwhelming and indisputable, yet he remains defiant. In an article, he insists that these findings are “totally false and without any evidence.”

Souri’s pictures have been published in numerous magazines and have been awarded prestigious prizes. Last December, Oskouei began contacting some of the publications and organizations, such as LensCulture (Holland) and Photoville (US) to stop promoting Souri’s work and to remove his pictures from their sites. Iran’s own Sheed Award, the country’s only independent photo prize, has suspended Souri from participating for one year.

Shahnavazi, whose project has been most affected by Souri’s photographs, has compiled a long list of awards he has received. Souri has amassed an impressive number of accolades for his pictures. By all indications, he has also made a considerable amount of money, but the director is not looking for restitution, he wants redemption.

As Iran continues to grab daily headlines, Western media’s appetite for unconventional visual stories continue to fall into deep rabbit holes, where there is no proper vetting. In some cases these stories are pushed by well-known picture agencies. Documentary photography and photojournalism is supposed to inform and shape public opinion, but certain narratives tends to reinforce stereotypes and an exaggeration of everyday life in places like Iran. Souri’s made up captions and photo essays fit perfectly into that mold.

Souri has managed to navigate his way to success by following a familiar pattern — make pictures by any means, particularly of women and girls, embellish captions, create alternative facts, give it a seductive title, then enter it into international festivals and awards.

Winning awards and prizes whitewashes facts and launders the truth. While successful in short-term, facts don’t change and always rise to the surface. As John Adams once said, “facts are stubborn things…” For Souri it took a few years, but his days of playing fast and loose with truth, with little regards for vulnerable subjects, and the directors who had brought him close to sensitive stories have come to haunt him with his own images.

According to Oskouei, the Iranian judiciary has summoned both Oskouei and Souri for an inquiry over the publication of Souri’s photographs from the correctional facility. Shahnavazi has also filed a legal complaint against Souri.

About the author: Ramin Talaie is a photographer, filmmaker, and producer based in Brooklyn, NY and sometimes San Francisco, CA. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. He teaches digital media as a part-time adjunct at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and makes short documentaries. He is also the creative director of Halcyon Studio, a video and filmmaking studio producing short documentaries and commercial videos. You can find his work on his website. This article was also published here.