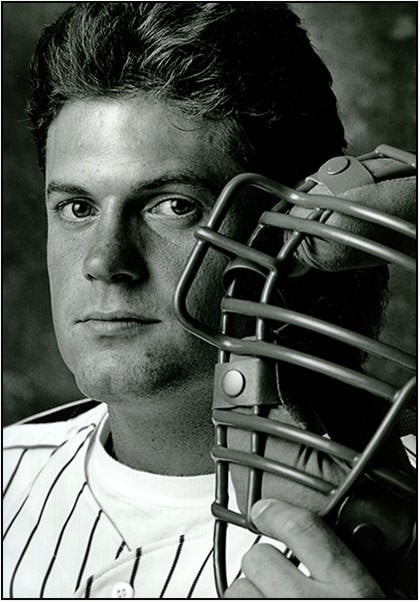

The Epitome of Cool: My Photos of the Late Baseball Star Darren Daulton

![]()

The past few hours of digging up and scanning my old files of MLB baseball star Darren Daulton have only made the pit in my stomach tighter. Sometimes looking through old pictures after someone’s passing is cathartic, but not now.

We weren’t friends; we were workplace acquaintances. But in the skewed world of photographer-athlete relationships, there were few that required fewer words or involved as many knowing looks.

Photographer-athlete relationships are complicated. We don’t talk to them every day like writers do. We work on the periphery basically unnoticed shooting the games, yet we are physically closer to the game than anyone but the teams and the umps. We literally rub elbows while we work. We make personal connections in portrait situations where they evaluate you individually; our deference to their schedule, our tolerance for their complete disrespect for our time, and the resulting picture.

Team photographers (as I was for the Phillies from 1987-94) have more access to players and let’s face it: a star player is a better connection than the backup catcher, but the backup catcher is likely more willing to talk to you.

Ideally, trust develops over time when either mutual respect or the simple resignation that you work in the same city, takes over.

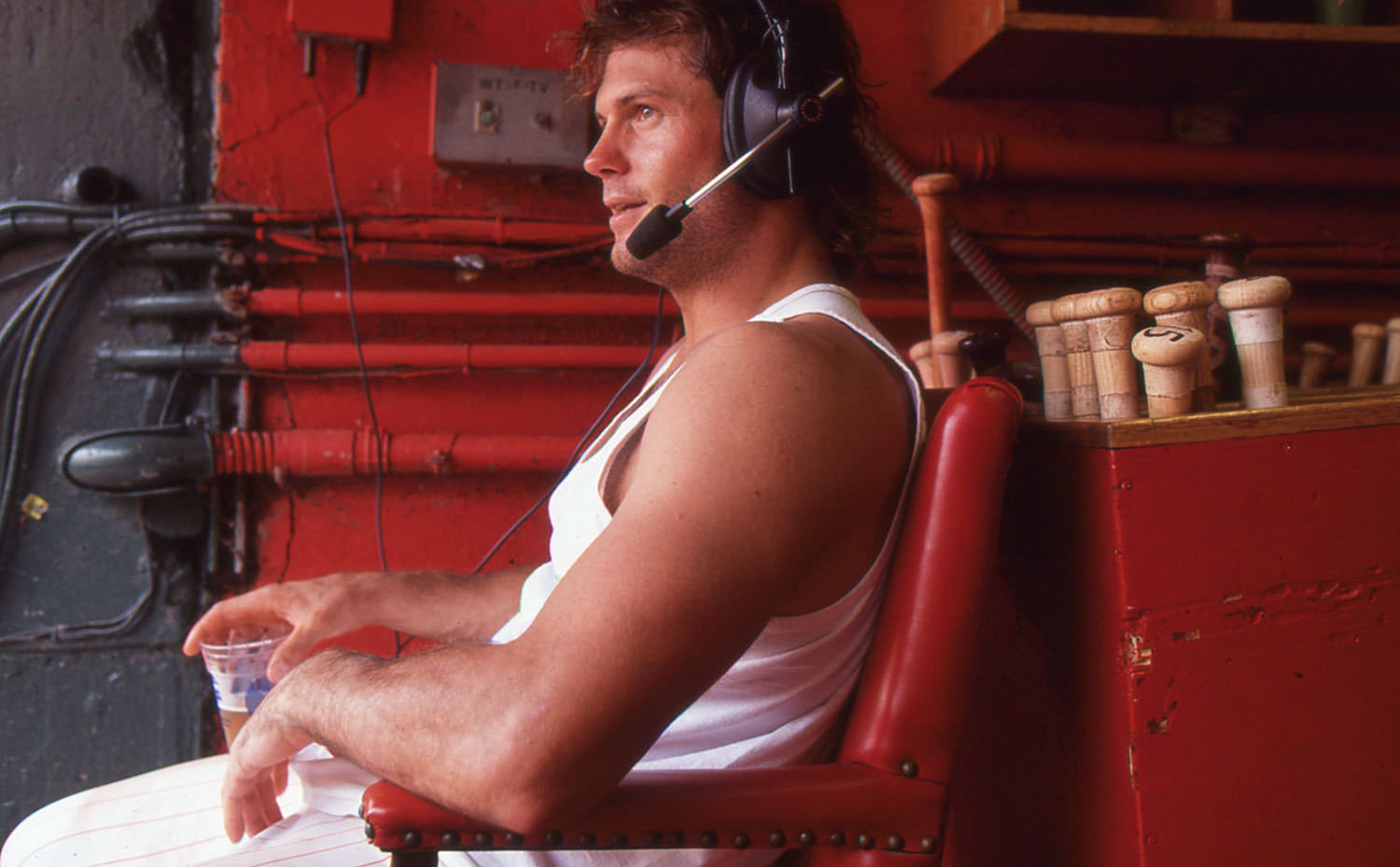

There’s a deeper mutual-use relationship team photographers and their star players have. Whether it’s an internal production or an outside assignment, the two end up in the same room more often than the other 24 guys. The advantage is obvious; the player doesn’t have to pose for a stranger and the photographer knows his subject’s quirks and attention span. It’s a matter of efficiency.

I was so green as a photographer in 1987 (I was 24) that I still considered myself a failed baseball player. I got over that quickly when I realized I was roughly the age of the players, but about the size of the batboy. However, my HS baseball coach played in the Phillies Minor league system, and I soon realized I literally spoke their language.

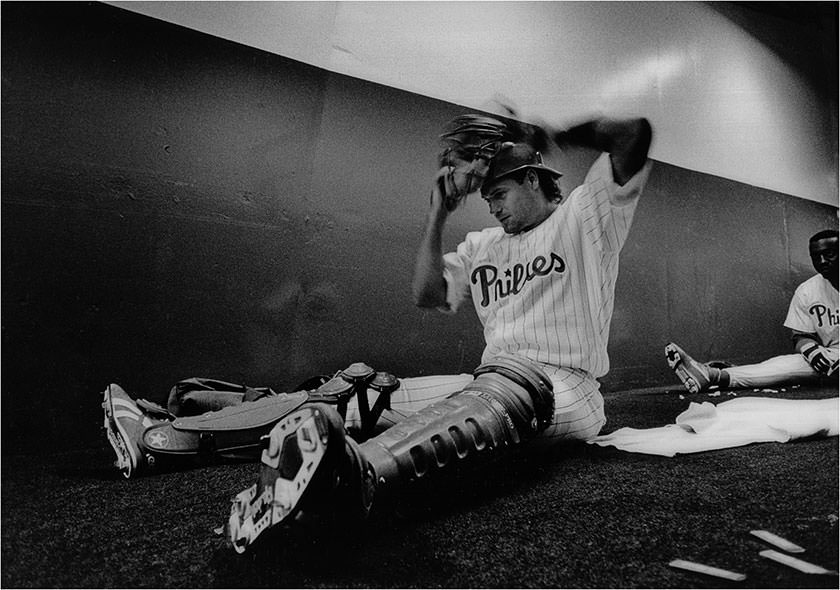

My first season with the Phillies saw Darren bumped into a backup role by the free agent signing of Lance Parrish. The mild-mannered Parrish underperformed for two years and Darren took over in ’89.

I was a catcher, so I gravitated to Parrish and Daulton with baseball questions and caught Darren by surprise a few times to the sweet sound of, “Al, now how did you notice that?” Early one spring training I asked why he’d changed his elbow position at the plate, and then we chatted about the different way he, and then-backup John Russell, tailed their throws into second base. I immediately noticed a change in our relationship after that.

What made Darren special was that he changed very little as lead actor in a high school musical (the ’89-’92 Phillies) to the sexiest man alive on the hottest freak show on earth (’93). The strut was always there, but his voice didn’t get louder, the barely discernible drawl no deeper, and the respect for others actually seemed to grow well beyond the MLB standard.

Darren Daulton was the epitome of cool. He kept his head down and persevered.He knew when it was HIS time and took over. He survived the worst the Philly fans could dish out to earn their outright adoration. And he gave Philadelphia the greatest gift: an unforgettable summer.

As I looked through my archives, almost every meaningful picture was made that year; eight brilliant months when the rest of the world could not avert their gaze from the supernova that was Darren Daulton’s 1993 Phillies.

In 1997 Darren was traded to the Marlins and a few months later, on a cool October night, we were face to face again. Surrounded by the chaos of his team celebrating a World Series Championship, he stopped pumping his fists, I lowered my camera, and both smiling, we silently shook hands.

About the author: Al Tielemans is an editorial, corporate, stock, and advertising photographer based in Pennsylvania. A long time Sports Illustrated contributor, Tielemans has over 100 SI covers to his credit. He has covered 13 Olympic games, 25 Super Bowls, 23 World Series, and countless feature stories with the great athletes of our time. You can find more of his work on his website. This article was also published here.