F**k Photojournalism: It’s Time for the Industry to Change Before It Dies

![]()

If you were to ask me whether or not I was surprised that there is another scandal in the photojournalism community, I would reply with a resounding and exasperated, “Hell no.” It seems that we can’t go a year without a new photo manipulation scandal. The Souvid Datta scandal is no different.

There is, however, one big difference I am seeing to a similar scandal from last year, Datta is being put through the ringer (which he well should be), because he got caught too early in his career and as a result, he is finished. This man will probably never work again. But others have done the same and lived to work another day.

Let me take you back to 2016, when it was revealed that Steve McCurry had been manipulating images for an astoundingly long time. And these were no small manipulations; entire people were being removed from photos. Like Datta, McCurry was outright manipulating the information present in his photographs, violating the very photojournalistic ethics that he had led his audience to believe he followed.

Here are a few examples from PetaPixel’s article published last year:

![]()

![]()

There was outrage; there was a call for an explanation, and for a long time Steve McCurry was silent. He later came out as saying that he “define[d] [his] work as visual storytelling,” swiftly blamed his staff, and then went silent again, and that seemed to be the end of it. I never heard about this issue again. Even more enraging was that just a few months later during a trip to Brussels, I saw a massive Steve McCurry exhibition on display in one of the city’s biggest museums.

“F**k Photojournalism!” I thought.

With the current Datta scandal at hand there are two major issues I think need to be addressed. The first one being why some photojournalist and documentary photographers can get away with gross violations of photo ethics, while others can not. I think the answer lies in what I mentioned above. When you get to a certain level of prestige you are untouchable. Steve McCurry is one example; Robert Capa is another.

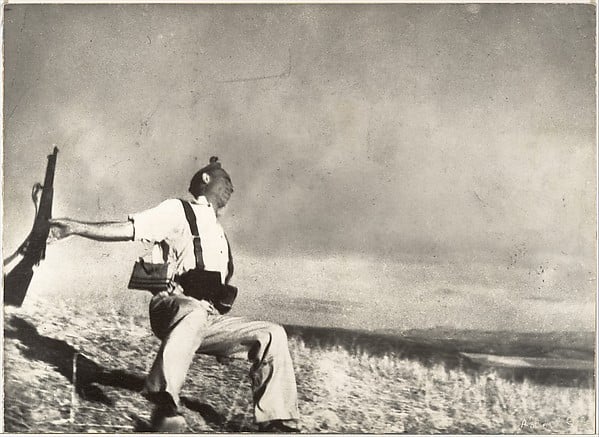

Many of us know Robert Capa from this photo,

What some of us may not know is that there is also this photo,

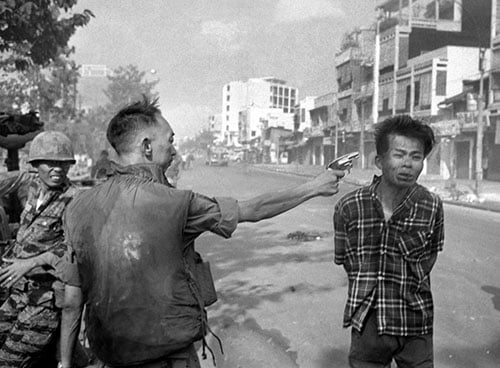

Catching the moment of death for a soldier once; astounding! Catching it twice; extreme probable cause for manipulation and fabrication. How many other instances can you think of where a photographer catches the moment of death in combat? Aside from the Eddie Adams execution photo, let me tell you, they are few and far between.

There is now the belief in parts of the photojournalism community that Robert Capa most probably fabricated these images, setting up scenes with soldiers and making them reenact them again and again and again. The scandal was raised in the New York Times when they reported how José Manuel Susperregui asserts in his piece, “Shadows of Photography” that the location of the photographs was not close the front lines as previously asserted, but rather 35 miles away and that the previous belief that the soldiers were being cut down by a sniper was impossible given the landscape of the region the photos were shot in.

This gave probable doubt to the legitimacy of the photographs and thus, as with all forgers, when you can’t trust one photograph, you can’t trust any of them.

But what is the most frustrating aspect of this scandal? Robert Capa is a founding member of Magnum Photos, the most prestigious photo agency in the world, and therefore, like McCurry (who is also part of the agency), he is untouchable. The Capa scandal has disappeared and we photographers keep repeating his annoyingly poignant quote, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough.” To which I say, “F**k you, Robert Capa!”

If some photojournalist can get away with this, then the industry is dead. Why should we ever trust it or even ourselves?

This also brings me to the second issue at hand. There is a very specific reason people are faking their work: to get awards. And when people are faking their work to get awards, it is not just because people have lost sight of why photojournalism is important and necessary, it is because the awards have become predictable; they have become a paint-by-numbers game.

I have noticed some trends in photography awards and grants lately. First, these organizations tend to surround around the same issues as each other from year to year; I feel like I can pretty much place a solid bet on what photograph or story will win what award these days. Second, there is an unspoken right and wrong story/photo to make; photos are starting to look the same and stories are starting to look the same as well. And three, the people and news outlets who win these awards tend to be the same people and news outlets from year to year.

Many awards are reserved only for ‘reputable’ news outlets, which tend, in my opinion, to be old news outlets. Thus, if you can crack the code to image making, choosing the right theme, know the right people, and don’t mind exploiting that very system, then you too can become a ‘great photographer’.

I’d like to focus more on the issue of the right and wrong theme in photojournalism in this article with one example in particular. Recently, I have noticed that the lucrative and popular theme at the moment overwhelmingly seems to be guns. Burhan Ozbilici won the World Press Photo Award for his truly astounding images of the assassination of Andrey Karlov, the Russian ambassador to Turkey. This was a controversial photo but not a surprising win.

Sarah Blesener has won both the Alexia and the Catchlight grant for her story “Toy Soldiers” about the growing nationalism among youth in the U.S. i.e. kids with guns.

Tomas van Houtryve also won a Catchlight grant to document developments along the U.S.-Mexico border using surveillance imaging technologies and further exploring the “weaponization” of photography; the camera as a gun.

Johnny Milano and Joao Pina, runners up to a prize Datta won with Visura, were acknowledged for their works “White Power Worldwide” and “Gangland” respectively which, you guessed it, also feature guns.

Just to name a few.

The only organization that bucked the gun trend this year to any notable degree was Photo of the Year International.

But if you don’t want do a story on guns, don’t worry, there are a number of other themes out there that will work; extreme poverty, drug use, border issues, immigration, and human trafficking (Datta won for this theme) are all particularly lucrative at the moment. Like it or not, even in the photo ghetto, the “if it bleeds it leads” rule is still all too present.

Now before I start sounding too bitter let me just say that I do believe that these stories are important and need to be told, but when they dominate the media landscape then equally important, but smaller, quieter stories fall by the wayside. We as an audience and industry develop tunnel vision.

News organizations and foundations have to remember that photojournalism is not a competition but a conversation. It is very hard to watch an industry at it becomes more and more closed off. The same photographers and news outlets can’t monopolize the awards scene if we want to survive. We need new stories. We need new photographs. We need a new visual language. And we know we need this. We are seeing the fruits of our complacent, “if it bleeds it leads” tunnel vision in society today and I don’t think I need to hint to (at least the western) public how those fruits have come to bear.

I do not feel incorrect in stating that organizations are very much be part of the problem. One example of this is the allegation against World Press Photos on their award to Hossein Fatemi, written by Ramin Talaie, which I highly recommend you check out. World Press has defended their award and yet, when I read the investigation by Talaie compared to the response from World Press, I can’t help but feel that World Press’ defence falls flat.

Similarly, the “International Center of Photography in Manhattan, where Capa’s archive is stored, said they found some aspects of Mr. Susperregui’s investigation intriguing or even convincing. But they continue to believe that the image seen in ‘Falling Soldier’ is genuine, and caution against jumping to conclusions,” as stated in the New York Times article mentioned earlier.

The fact that a highly respected photojournalism organization can state that allegations against the legitimacy of an archive are simultaneously, “intriguing or even convincing” while still believing the work is “genuine” astounds me.

The epidemic we are facing now goes in both directions; too many photographers want to be famous and win awards, and too many photojournalism organizations have fallen into the trap of always awarding photographers for the same types of stories. And every year when this happens photojournalism organizations “mourn the loss of trust” and denounce the photographer as they are expected. That is not to say that their feelings are disingenuous, but it is time for everyone to take a long hard look in the mirror and start taking responsibility for their role in this industry we are trying to live and work in.

It is time for the industry to change before it dies completely. Or maybe it is even time for the industry to die so something better can come in its place. Not enough photographers are getting credit for quiet, subtle and heartfelt stories and not enough photojournalism organizations are brave enough to shake up their view of what a profound photojournalism story looks like.

We created this monster. If we don’t act now we will soon be saying “Photojournalism is dead! We killed it!” And if that is the case then I say, “good riddance and f**k photojournalism!”

About the author: Clary Estes is a photographer based in Moldova. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can connect with her through her Facebook and Twitter. This article was also published here.