Inside the Lab of an Electron Microscope Photographer

![]()

David Scharf is a basement pioneer in the art of making some of the world’s smallest things appear huge.

Back then, most electron microscope photographers took out-of-focus photos of dead and dusty specimens. Their tiny subjects had to be coated in gold or platinum for the microscope to see them.

Scharf realized that living subjects could be photographed without a coating and pioneered a new technique that allowed him to take photos of the unseen world while it was still breathing.

This technique quickly catapulted him on to the pages of TIME, National Geographic and Newsweek.

Today, Scharf operates out of his Echo Park home where he’s creates images and movies of organisms like jumping spiders and honeybees during his nightly sessions.

Scharf is a perpetual night owl he wakes up around 3 p.m. and works the through the night as his dog Layla lounges nearby.

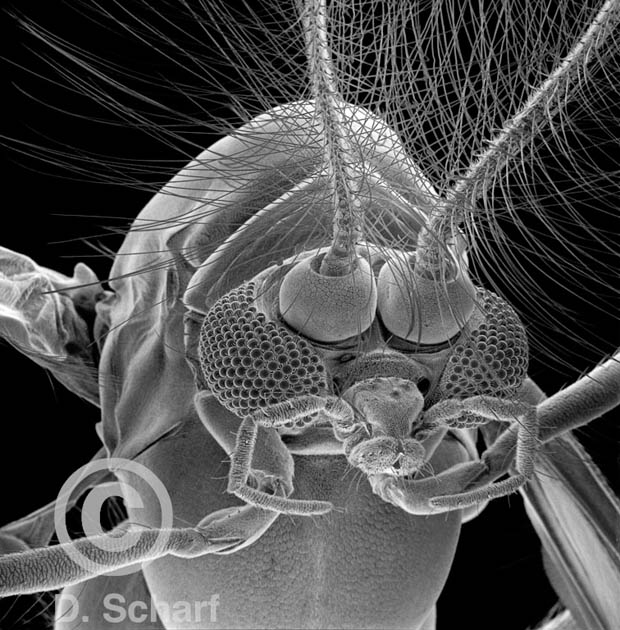

When he peers into the unseen world, sometimes he doesn’t know what to expect. He’ll focus in on a moth fly the size of a speck of dust and uncover whole worlds.

“Each eye looked like a moon out of Jupiter or Saturn. It was like a little garden in there,” Scharf said.

His electron microscope zooms in on the eyes of that one-millimeter moth fly about 1,000 times over.

“When you start looking at the complexity of all these earthlings, it’s absolutely mind boggling. It still blows my mind,” Scharf said.

Scharf invited me and Off-Ramp reporter Kevin Ferguson down to his lab to see how electron microscopy works.

Inside the Lab

Scharf’s lab is located inside his Echo Park home that he’s had since the ’70s.

![]()

![]()

Scharf almost always uses living subjects. When we visited, he had a few leftover Anopheles mosquitos from his a cover story for National Geographic about malaria.

![]()

Scharf often puts the live specimens into the refrigerator or sprays them with carbon dioxide to get them to stay still and mounted to a dish.

“That usually calms them down and then they wake up and their butts are glued down,” Scharf said.

Then, he looks at the samples using a regular light microscope to carefully put them in place for the scan.

![]()

Scharf is always tweaking and refining his own equipment with techniques he learned as an electronics engineer.

![]()

Before he switched to digital photography, Scharf used large-format film attached to a control panel that looks like something out of “Dr. Strangelove” (pictured below).

![]()

![]()

His early images came out black and white. Scharf would spend dozens of hours painstakingly coloring them in. He spent 40 hours on an image of Ragweed pollen (pictured below).

![]()

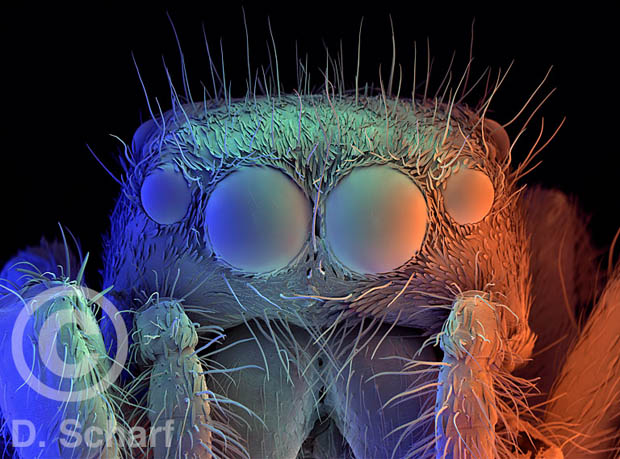

In 1991, Scharf created a new system for colored images that uses three electron detectors at different angles. The individual detectors are calibrated to red, green and blue like older television sets.

The data from the three detectors are combined to make his multi-colored images.

![]()

Today, his system is hooked up to a computer, and the electron information is beamed straight in.

![]()

Here is a selection of the beautiful electronic microscope photos Scharf has created:

After all his years looking at the what nature has to offer, Scharf says now he just lets “the universe do what’s best for me and try to hear the signals and follow.”

About the author: Mae Ryan is a photographer for KPCC, the local NPR station in Los Angeles. KPCC recently launched AudioVision, “public radio for your eyes.” You can also find AudioVision on Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr. This article originally appeared here.

Image credits: Photographs by Mae Ryan/Kevin Ferguson/KPCC and electron microscope photos by David Scharf