Interview with Rock & Roll Photographer Oliver Monroe

Oliver Monroe is a Los Angeles-based photographer who has photographed some of the world’s most famous bands and music artists in concert. Visit his website here.

![]()

PetaPixel: Can you tell us a little about yourself and your background?

Oliver Monroe: I grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, where my dad worked for the Department of Defense. In 1979, I moved to Los Angeles to further my career as a photographer. After nearly 10 years in the music/entertainment business, I hung up my camera bag and became a commercial film editor for the next 5 years. Wanting to see daylight again, I left editing and started a multimedia development company. I currently own a video encoding company, which caters to the entertainment industry.

OM: My dad had a 35mm Yashica rangefinder camera. I was curious, and started to take pictures with it.

I loved the process right away, and got myself a job when I was 17 in a local camera store. There I learned the ins and outs of all the different gear. I convinced my dad to lend me the money to buy my first SLR, a Nikon FM with a 50mm f/1.8 lens.

Having access to lenses from the camera shop — and a nice discount on film — I would spend the next few months experimenting as much as possible, and building a small portfolio of my pictures.

Several months later, I met a guy who owned a stock photo agency around the corner from my work, and I ask him to check out my pictures.

He said I had potential, and suggested that I build a portfolio and return to see him in a year or two. I was impatient and wanted to learn as much as possible about photography. I started hanging around his stock agency, working for free, sorting 35mm transparencies, and doing general office work. I learned a lot by looking at the style and techniques of their professional photographer clients.

After a while they gave me small local assignments. They did not pay much, but it it was gratifying getting paid to shoot.

One Friday morning in the dead of winter, the owner of the stock agency told me they received a rush request from a international magazine for interior photos of a church in Washington. He said his local pros were out of town or not available on short notice, and asked me if I wanted to give it a try. He said the film had to be developed and ready to ship by Monday at 10AM.

I ran to my apartment, grabbed my camera bag and hopped on a bus for a trip across town. It was snowing non-stop all day. This was no church I had ever seen. There was a sign to leave your shoes in the front room. I took off my shoes, went into the main area where I found 30-40 people kneeling on the floor. At this point I felt a bit uncomfortable, but did not want to leave empty handed.

The magazine wanted pictures of the celling, I quickly realized this was not possible without a tripod since it was dark inside.

I pulled my camera out, attached a flash and kneeled down and started to shoot.The flash bounced off the gold dome roof and created a sun-like effect.

The next thing I saw was a group of men yelling at me and coming towards me with what looked like small letter openers.

I turned around, ran to the door, grabbed my shoes, and started running in the snow away from the building. After about 10 minutes, I realized they were not letter openers, but miniature daggers. Then the light went off in my head regarding why no pro shooter from the agency was available for this assignment. They knew better than to risk their lives.

I went home and processed the black & white film in my makeshift darkroom in my bathroom, and delivered the film to the agency.

The magazine purchased 2 of the pictures, and I got paid $400 per picture.

A few weeks later, I met 2 guys who were in the process of setting up their own media company. Their office was a renovated warehouse. They built a large screening room, which could seat about 100 people. One of their services was to screen first-run Hollywood films for the super rich and for political figures. At the time, some of the Hollywood studios would make 16mm prints available for rent for large sums of money. I had no clue how film projectors worked, but Harry & Neal showed me the ropes and let me hang out and learn from them. Although I was more interested in photography than being a projectionist, it was all new and mechanical and cool to be around.

The other part of their business was shooting local D.C. functions and news events (on 16mm pre-portable film video cameras) for Black Star picture agency in NYC. The agency, I was told, had clients in the Middle East who requested the news footage.

Harry & Neal had 3 freelance shooters working with them regularly. One day, one of them could not make it so I was told to rush home and get dressed for something fancy. Before I went, Neal ask me for my Social Security Number. I thought this was weird, but he said, “you will see soon why I ask for it”. When I got back, he hailed a cab, filled the trunk with all the gear, and told the cabbie go to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

It did not register with me at the time, so when we pulled up to the White House, I got real nervous. Neal said the Secret Service needed my Social Security Number to run a criminal background check on me. We went to an adjacent building where the press corps was waiting.

After the Secret Service looked through all the gear, they took us through a underground tunnel to The White House where minutes later we would be standing behind a rope in the Oval Office, with President Jimmy Carter behind his desk. The Secret Service controlled the lighting rigs, and no one was allowed to shoot till they turned them on. Neal was shooting 16mm film stock, and he told me to shoot as much as possible with the still camera. It was a fantastic day for a 17-year-old kid. And as it turned out, I got to go back about 10 more times over the next few months.

PP: How did you end up in the music and entertainment business?

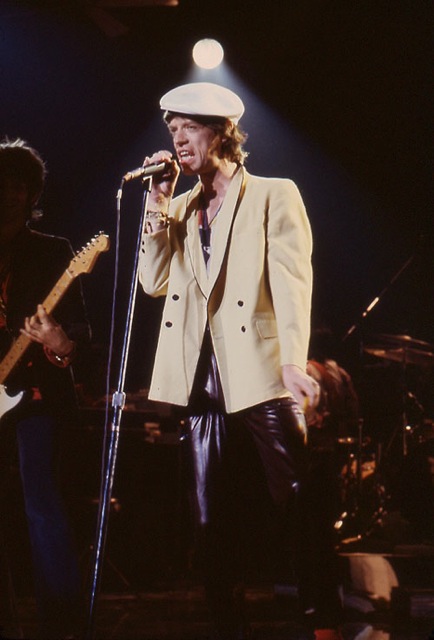

OM: When I was 10 years old, my best friend and I played Rolling Stones records all day long. We were so into the music, and I told my friend that I would meet the band someday — I just did not know how that would come together.

One day, I told the owner of the stock photo agency that I wanted to shoot rock & roll concerts.

The agency specialized in sports and political photography, not entertainment, and they were not that interested. After a few weeks of nagging them, they issued me a very official-looking press pass with my picture and the agency stamp on it. They made it clear they could not get me any assignments, but if I could come up with great rock & roll photos they would try to sell them. The owner gave me three pieces of advice: (1) Do not make us look bad (2) Dress professionally (3) Project confidence.

It was 1977, and The Ramones were in town for a few shows. I went down to the club where they were performing and showed my press pass at the box office. They got the tour manager, who asked me where the pictures would be published. I told him the agency would send them to all the major entertainment publications.

He said, “Come meet the band backstage,” opened the dressing room door, and yelled, “Hey guys, meet Oliver, he is a photographer.” I was scared, but walked in and started shaking all their hands to steady my nerves. I then dove right in, took a few pictures of the band getting ready backstage, and then shot the show from in front of the stage.

It was a major adrenaline rush.

Afterward, I took the slides to the agency. They loved them, started to pitch magazines, and ended up selling 10 images.

At this point I recognized that music photography was in my DNA, and I wanted to do it full-time.

One morning, in June of 1978, I heard on the radio that the Rolling Stones were playing a one-night gig at an intimate DC venue: the 1800 seat Warner Theatre. I raced down there at 8am, to find 20-30 photographers, reporters, and news crews trying to get access to the band. After a couple of hours I finally got to speak to the Stones publicist, who said it would be a slim to no chance of getting in to shoot, as there were only 2 photographers allowed. Period.

He told me to wait, and that he would see what he could do. After another couple of hours, most of the other photographers had left. He kept coming out front every couple of hours, telling me he was trying his best for me. This went on for 11 hours. I was sunburnt and beat from standing most of the day with my all my gear. At 8PM, I heard The Stones start to play. Thinking the shoot was not to be, I gathered my gear to pack up and head home…

At that moment, the publicist came rushing through the front door, grabbed my arm, said, “Lets go kid,” and pulled me through a maze of security guards. While we were moving through the lobby, he put a black garter belt on my arm in lieu of a photo pass. As we were making our way down the aisle towards the stage he said, “You have 3 songs to shoot in front of the stage, and then you have to move to the side.” He walked me right to the front. The stage was 3-feet-tall and I was touching-distance from Mick Jagger.

My heart was beating so fast. Finally, the band I loved so much was right there in front of me. I just kept shooting throughout the first 3 songs almost non-stop. When I had to move to the side, I looked over and saw the other photographer. It was Annie Leibovitz.

It was an incredible day. The agency loved the photos, and sold them domestically and internationally.

A few months later, I moved to Los Angeles in pursuit of becoming an entertainment photographer. This proved to be a bit more difficult than I had envisioned. I quickly realized that I needed to learn the skill of selling myself. To support myself, I got a job in L.A ‘s largest camera store where I got access to a lot of gear and made some good connections.

I also began to cold call all the record companies publicity departments. It took a while, but I landed some interviews. They liked the photos in my portfolio and gave me some assignments. With a few ups and downs, I quit the day job and started ringing the phones off the hook for everyone I could find in the music business. Rejection comes with this job, so I had to grow some tougher skin and forge ahead. After a few months, I had some steady record company clients, which was great.

Then one day, I met the L.A. bureau chief of a leading European entertainment magazine. She was a tough, demanding, and always on the job — a real workaholic. This worked well for me, because all I wanted was to shoot. She would give me a lot of great assignments. The deal I struck with her was that the magazine would get me the access in the form of a photo pass and pay for expenses including film and processing. In turn, she would get first look at what I shot. She bought the best shots for the European market. It was a win win and exposed my work to a wider audience. I could sell the other images to stateside publications.

It all started to snowball for me after that. I would shoot concerts for record companies in the evenings, and during the day I would shoot interviews the European magazine was doing with film & TV celebrities. After a few years, I was too busy to shoot and sell at the same time, so I signed with a entertainment photo agency in NYC. Once again, this worked out well, as they had so many contacts that it quadrupled what I could earn from my work.

When I was not shooting music, I was fascinated with the “new” technology of the time: the Polaroid SX-70. I loved the square format.

Polaroid came out with a SX-70 SE model with a higher-quality lens and a promo where Polaroid would replace any 10 pictures you did not like with a free pack of film. I shot thousands of pix with that camera, and Polaroid noticed it. Their marketing rep called me one day asking if I be interested in showcasing my photos in exchange for unlimited film. I did the deal. One day, they offered to purchase 100 images for their new marking campaign.

The offer was $35,000. I was ecstatic, as that was a lot of money for a 22-year-old kid. When they sent the contract, it stated that they were buying the images, not licensing them from me and there would be no photo credit. I could not do it. It felt wrong to me.

I ended up framing them, and hung them on my walls. Over the years I gifted them to friends who loved them as much as I did.

Before I knew it, 6 years had gone by and I had logged a lot of miles, photographed many bands, and wore out a few cameras.

PP: What are some of the most famous bands and artists you’ve photographed?

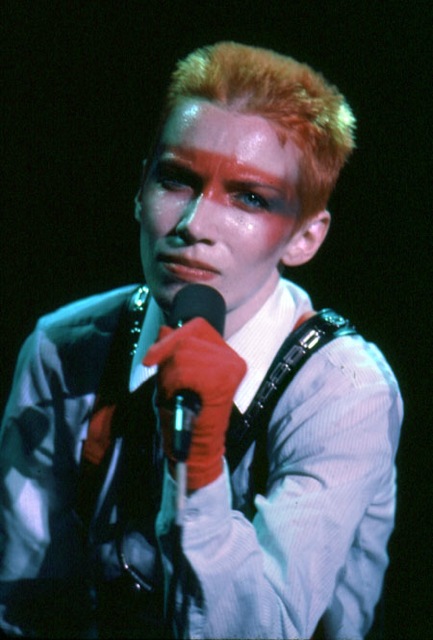

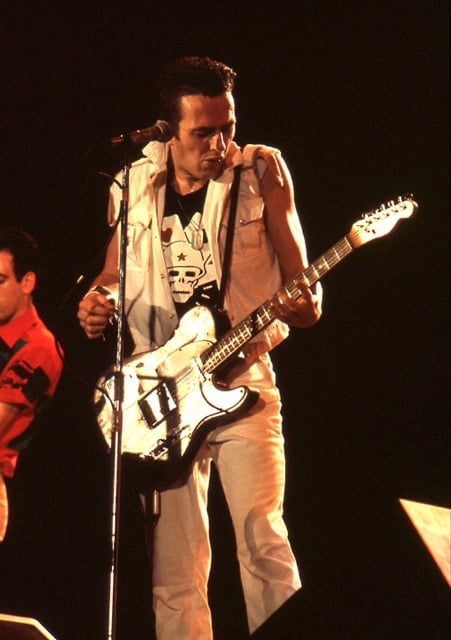

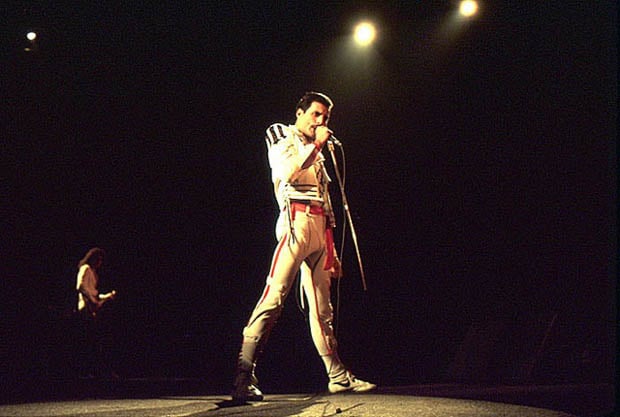

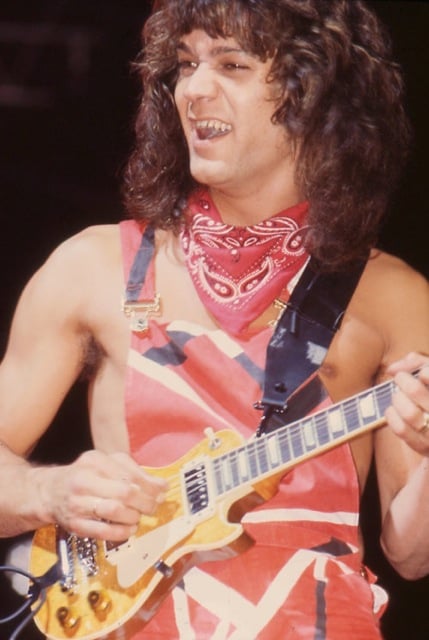

OM: As I mentioned above, I started with The Ramones, then The Rolling Stones, and then others came over the years to come. Bands like U2, The Clash, Queen, Van Halen, Annie Lennox, Scorpions, Peter Gabriel, David Bowie, The Police, Ozzy Osbourne, The Pretenders, Talking Heads, Fleetwood Mac, INXS, Joe Walsh, Rush, AC/DC, Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers, The Cars, and The B52’s.

PP: Any interesting stories from your time shooting famous rock stars?

OM: A popular hang out for rock & rollers back then, and still is today, is The Rainbow Bar & Grill on Sunset Blvd. When I was not shooting concerts, I would hang out there and mingle with PR folks from record labels. One rainy night I was leaving the Rainbow, and next door is The Roxy Theatre (a wonderful, small club to see a band perform). I heard Reggae music coming from it, and as I was standing there listing, the door opened up and Keith Richards stumbled out. We made eye contact, and started chatting. After a few minutes, the door swung open again, and out came Mick Jagger. They were there for the Peter Tosh concert, who was on Rolling Stones Records at the time.

Mick and Keith started to argue, and it looked like a fist fight was about to begin. Then, I did a stupid thing: I got in-between the two to try and mellow the situation… That did not work, as I ended up on the sidewalk a few seconds later. The Roxy’s bouncers finally came out, pulled them apart, and shoved them into separate limos.

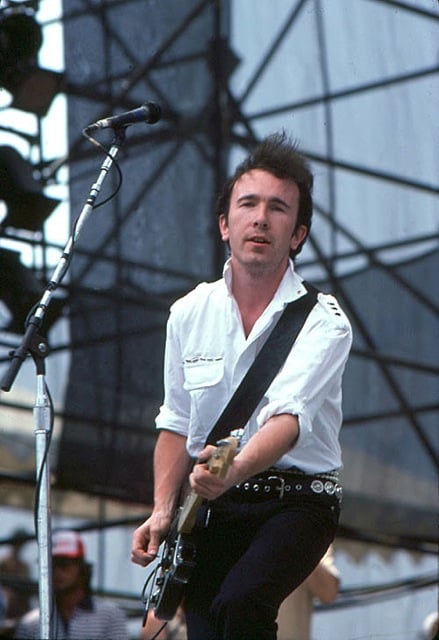

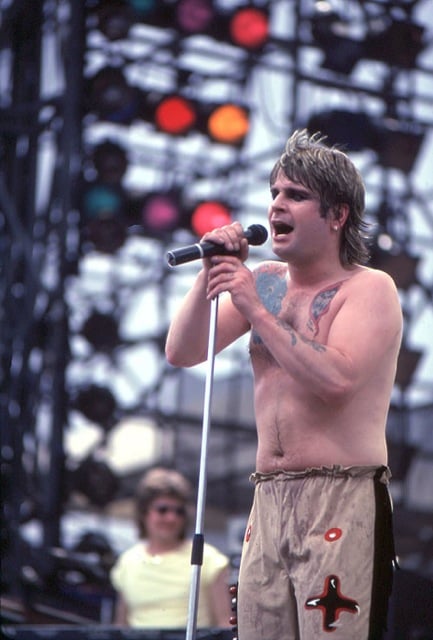

Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak financed the 1982 and 1983 US Festival in Glen Helen, CA, a 3 day rock festival with about 550,000 visitors. I was there for both, and it was a mad house. As I recall, on Sunday, May 29th 1983 (Heavy Metal Day), Van Halen was scheduled to play. About 2 hours before their set, David Lee Roth found out that David Bowie (who was performing the next day) was the highest paid act at the festival. For whatever reason, this irked D.L.R. and he refused to go on stage unless he was the highest paid act. This sounds silly now, but it was a huge problem for the promoters then, as there were hundreds of thousands of people amped up to see Van Halen. I was in the photo pit, and only 20 feet from all these wild fans, and all I thought about was that if VH does not play, I was a dead man… Luckily, the promoters paid up and the show went on with a sigh of relief from all the crew in the front of the stage.

I got a call one day to shoot an interview with the singer of a then super-popular band. I showed up at the managers office where the interviewer was waiting. I knew her; she had a abrasive personality. I had a bad feeling there, and 20 minutes into it, he walked out.

The manager got him to come back, and said no more questions about his family. The interviewer backed off for a while, but towards the end of the interview she came back to the family questions and that pissed the artist off. He grabbed a bottle of Jack Daniels, took a swig from it and then tried to slam it at the wall. As the bottle was leaving his hand, it started to spin and I could see it was coming my way. It missed my head by about an inch, and broke apart on the coffee table and the liquor spilled all over my gear… The manager replaced the gear, it was the last time I worked with an interviewer whose instincts I didn’t trust.

Bravo, a magazine that I worked for a lot back then, ask me to shoot some pictures of an up-and-coming European artist named Falco. I met the magazine reporter at A&M records in Hollywood. We did the interview and pictures, and as we were rapping things up, Falco told the reporter he wanted to escape the endless hours in the record companies office. He wanted to see L.A.

So we kinda kidnapped him, drove around Hollywood, and got great pix of him which ended up as a full page spread in the magazine. The record company was not very pleased that their artist was missing for 6 hours (pre cell phone days). In the early 1980s, the Rock & Roll scene was fully engulfed in excess of alcohol, cocaine, and prescription drugs.

I have many more wild stories, but most won’t see the light of day.

PP: Have any good concert photography tips you can share with us?

OM: The first thing to get is a good pair of ear plugs, especially if you plan on shooting rock & roll concerts. I learned this the hard way, because I was stubborn and did not think I needed them. But I did, as my ears were ringing for days after many of the concerts.

Use a camera that has a good burst rate, as some artists move around a lot on stage. Depending on your access, you may only need a wide-to-medium telephoto zoom lens, cutting down on gear you have to carry. I tried to keep the shutter speed at 1/125th of a seconds or above whenever possible. Most artists hate when a flash is going off in their face, so that is not recommended. I would use lenses that have fast autofocus servos, as the action happens quickly at concerts.

Learning how to frame the shot properly is a big plus. And in rock & roll photography, be on the lookout for guitarist doing guitar sweeps at the edge of the stage — my camera got smacked a couple of times when I was too close to the action.

PP: What’s the biggest lesson you’ve learned so far in your career?

OM: I am on my third career, and the one lesson that has spanned all three is “When life knocks you down, try to get up right away and try again.”

PP: What’s the toughest thing about shooting musicians and their performances?

OM: The toughest thing in the beginning was not having enough time to shoot. I would get a photo pass that allowed me to stand in front of the artist for the first 3 songs. This sounds great, but most artists need to warm up and get into their “Groove” and feel the audiences energy. They don’t loosen up until maybe song #5 or later. So, the pix you get in the first 3 songs can be less energized than those shot later in the show. After doing this for a little while, I would chat up the road managers for a laminate all-access pass that would allow me to shoot the whole show. And a lot of times, the best pix came from the middle of the concert.

PP: What advice do you have for someone interested in pursuing a photography career in the music and entertainment business?

OM: I think, if possible, one avenue would be to hook up with a band. Do their tour photography, and get paid to shoot it. Most likely they will own the pictures. If you negotiate a decent contract, you could use some of the images for your portfolio. The entertainment photography business has changed in a big way (and not for the better for photographers) since the days I was doing it. Unless you have good connections that can get you access, you need to cold call band managers, PR agents, record companies executives, magazine editors until they are sick of listing to your voicemails and will take a meeting with you, just so you can show them your pictures. In person, face-to-face meetings got me 80% of my work. Do not take “No” for an answer.

And remember what Steve Jobs said, “Love What You Do” and “Follow Your Heart” always.