What Does Nikon Excel At?

![]()

With Photokina coming up later this month, we’ll soon have a good chance to see whether Nikon is playing to their competencies or incompetencies with their next round of announcements. Every company has some core competencies that can’t be denied. What are Nikon’s?

With lenses, Nikon’s best efforts seem to be in optical VR, glass consistency, glass attributes, coatings, and lately an interesting twist where the optical design is to targets that don’t always conform with the old MTF, CA, aberration assumptions.

These are all deep R&D projects that eventually bubble up into features in products.

Yet there are core incompetencies evident at Nikon, too: consistency in product line management, lackadaisical marketing, poor customer support, terrible user software, poor communications with other devices, total lack of ecosystem management and enhancement, an insular and bloated upper management scheme that’s perpetuated the worst of Japan management practices, and a huge dose of NIH (not invented here).

The deeper in a product something is developed, the better Nikon is at it, it seems. They’re an engineering company with some remarkable designers that are great at looking at very low level problems and finding solutions to them. If I had any electronics or optical hardware product and needed to iterate it into something better, I could do far worse than having Nikon’s best R&D teams work on that problem. In fact, I might not be able to do better.

But somewhere between that low level work and the final product we often see the incompetencies start to mask or modify the competences. Nowhere was that more obvious than the Nikon 1.

![]()

The original Nikon 1 models had fewer total parts than any sophisticated camera I’ve seen (less than 300), and a manufacturing build program that anyone reading this could learn quickly and completely. Yet somehow the resulting cameras were more expensive than most of Nikon’s consumer DSLRs. Those Nikon 1’s had focus performance that other mirrorless cameras took years to even approach, yet Nikon managed to design the UI so that your ability to actually control and manage the focus was terrible. Despite being a post-iPhone designed device and targeted through advertising at the “in young connected crowd” (remember the Ashton Kutcher ads?), the first Nikon 1’s had virtually nothing in them that would help you share, something that was already quite an evident need in that target market.

This isn’t the first time that Nikon has thought themselves a consumer company with consumer competencies (and been wrong). And I believe that the fundamental issue here is that Nikon simply doesn’t see, understand, or relate much to actual consumers. All of the things we love about our Nikon products come from deep within engineering programs at Nikon, and these somehow survive the process of making it into a usable product. Virtually nothing that Nikon excels at is rooted in solving customer problems. Everything they excel at comes from iterating and solving engineering problems.

I’d argue that you need to be good at both things—solving customer problems and breaking engineering constraints—to be fully successful in today’s tech world. Moreover, you have to move at innovation speed, not iteration speed. You can’t wait to see what proved to be popular (e.g. Facebook, et.al.) and eventually address that; you need to pick up trends as they happen and lock your products onto them like leeches.

None of this is easy. Products, companies, and even industries fail from time to time, and it’s often because they get the balances all wrong in their customer versus engineering problem solving. As good as the D500’s autofocus system is, one of the key things that holds back the D500 is the SnapBridge component, which is flakey, incomplete, and still doesn’t solve some of the workflow steps of the actual user problem it tries to address.

The good news, of course, is that the D500 isn’t targeted at Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, SnapChat, and other similar mass market users (though SnapBridge is, and it is going to be part of truly consumer cameras soon). The other user problem that the D500 addresses—focusing—is something that even the core serious enthusiast/pro appreciates being addressed. And thus the D500 does well among that group.

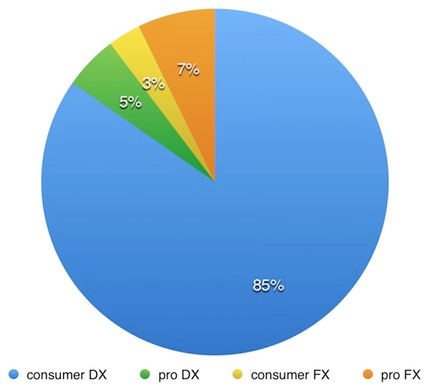

Here’s the trouble. I shared the following chart earlier this year:

The D500 is the only current product in the green portion of the pie. That big blue piece is where you absolutely have to solve customer problems in order to sell product efficiently. And that’s exactly where Nikon is struggling to maintain its grip at the moment. It’s where SnapBridge has to make a difference, not the number of focus points. Indeed, it’s where all of Nikon’s incompetencies come most into play, and where their core competencies help them the least.

What that tells me is this: Nikon can continue to struggle to grow—or worse, start to significantly shrink—by trying the same things they’ve done in the past and thinking that their engineering team will win the day for them. Or they have to address and fix their incompetencies. Simple as that.

For those of us who use the prosumer and pro DSLR bodies, we’re mostly happy with what Nikon has been feeding us. Yes, we can niggle and nag at little things, but the D500, D810, and D5 represent some of the finest tools we photographers have ever had. Hard to complain about that. Yet for Nikon to continue to be able to make those great tools we love, we need to see them protect the Imaging business with products that appeal to the far bigger consumer group. To do that, Nikon is going to add some competencies to their list. A lot of competencies.

About the author: Thom Hogan is a photographer and author of over three dozen books that combined have sold over a million copies worldwide. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of his work and words on his website. This article was also published here.