The Great Light Hype: You Don’t Need to Drop Big Bucks for Great Photos

![]()

“But, what about gear?” It’s a question I hear a lot. Broncolor or Profoto? Fender or Gibson? Lamborghini or Ferrari? Which toy/software/high-end piece of gear is the best so that I can do exactly what that photographer is able to do?

I’ve been asked why I opt for such a minimal or even anti-gear approach to photography, while other photographers laud gear upgrades. Well, it’s not a choice made on principle or even moral reasons; it’s one of preference. I like traveling light and working alone. A big gear kit requires help to haul it, room to store it, and money to fund it. No thank you. This was not a decision that I came to overnight, but one that was forged through years of working with the only gear I could afford.

When I first launched my business in 2007, all I had in terms of gear was a Canon 20D, one 430EX flashgun (which didn’t have a port for a transmitter, so I couldn’t use it off-camera), a piece of junk 18–55mm f/3.5–5.6 kit lens and a Sigma 70–200mm f/2.8 lens (without image stabilization).

![]()

Let’s say, for example, that I wanted to get an off-camera flash shot. I would put my camera on a tripod and do a long exposure, walking over to the subject and manually popping the flash (think light painting). It was far from ideal, but I sure learned the limitations of my gear. It also gave me plenty of time to think about what piece of gear I needed next.

If your eyes don’t work well, everything that you look at will appear out of focus or hazy. So it goes with camera lenses. Upgrading my glass, I decided, would need to come first. I shelved my kit lens in favor of a (used) 24–70mm L. Now I was in business. My image quality improved considerably.

The next step was getting a couple (affordable) flashguns with triggers, so I wasn’t running around, flash in hand, hoping it would be dark enough for me to do a long exposure. I opted for the LumoPro LP160 flash unit, purchasing two, along with three PocketWizard wireless remote triggers. The whole transaction set me back $600, which was a big number for me at the time.

![]()

Getting reliable light and a quality image enabled me to realize that my camera sensor—a cropped 8mp sensor—just wasn’t giving me what I needed. Even with good light and good glass my camera wasn’t up to snuff with other, more current bodies on the market. However, I still couldn’t afford the Canon 5D Mark II, which had just hit the scene. I got a 40D instead. Although the sensor was still cropped, the quality was a bit better, and because I was taking on more paid photo gigs, I needed more reliable gear—not to mention a second camera body, so I’d have a backup if one failed.

Seven years later, I now have the ideal gear setup, but it’s not identical to the setup of any other photographer. It’s completely mine, unique to my needs. If I had simply used a $10,000 credit card when I first launched my business and bought a bunch of gear that other people said were “must haves,” I would’ve cheated myself of the learning process.

My shooting and lighting process is now different from any other photographer’s because it had time to evolve and grow. Through this learning process, I have found that I need only two (prime) lenses and I prefer to use flashguns to studio strobes. In the rare occasion that I am shooting tight interiors, I’ll rent a 16–35mm lens, or if I am shooting jewelry, I’ll rent a 100mm macro lens, and add the rental costs to the client’s bill.

Don’t get me wrong. Studio strobe systems, such as Profoto, are fantastic—a luxury but not, I dare say, a necessity. They provide a consistent (high) output and color temperature. If I were strictly shooting in the studio, a Profoto system would be perfect—I even owned one for about a year.

Once I was making enough money in my business to afford one, I bought a used Acute2 pack with two heads, excited about the increase in power I would have. I was excited to shoot portraits in full daylight, eclipsing the sun with my output. The problem was not only did I need a 10-pound battery pack to accompany the already 25-pound light kit, but my lights were also tethered to the pack. The farthest each light could be moved from the pack was about 10 feet on either side, without getting extensions, which was more money and more weight.

Add to that, there were cords running everywhere and I needed an assistant to help lug the massive gear kit, which with light stands and sand bags was well over 100 pounds (before adding in the weight of my camera and lenses). This meant booking an assistant, which meant more money and planning and less spontanaity—no more running and gunning, which is how I prefer to roll.

After realizing this large light system was actually handicapping me, I sold the gear and bought some used Canon 430Ex Speedlites with RadioPopper wireless triggers, which allowed me to use high-speed sync (HSS). This was the mobile answer to eclipsing full sunlight, and now I was running and gunning again. Having flashguns rather than studio strobes allowed me to place them anywhere and easily reposition them so I could quickly dial in the lighting for a shot.

In the time that’s passed since I last owned a Profoto system, the company has released the more portable B1 and B2 systems. The B1, a 500-watt head, has the battery right in the head, while the B2, a 250-watt light, has a smaller, flash-sized head with a battery pack attached by a cord. For the sake of better knowing my options when it comes to portable light, I did a comparison between the Profoto B1 and the Cactus RF60 flash.

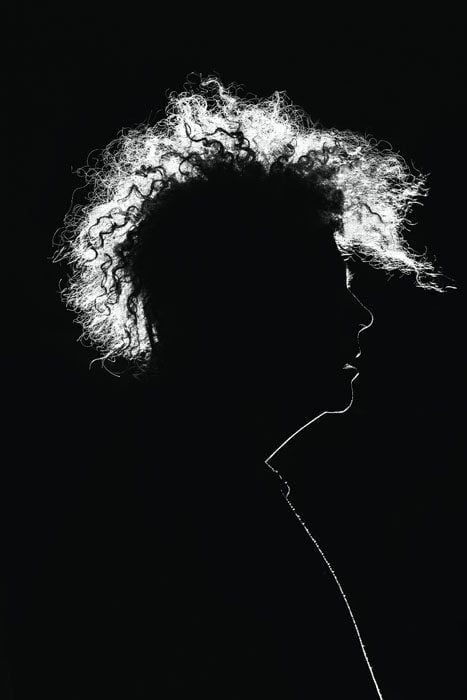

Although the Profoto lights have a higher output and a longer lasting battery, I still prefer the Cactus flashes, for several reasons. First, the size. For every B1 I put in a camera case, I could take four Cactus flashes. Second, the light and shadow quality. In the first portrait above you can see the straight out of the camera (SOOC) file from the Profoto—nice light but soft shadows. Compare it with the cold, crisp shadows in the second portrait, which was lit with the Cactus flashes. If hard light is what I’m going for, the victor is clear.

The one thing I’ll point out is that the light spread of the Cactus flashes isn’t as broad as the Profoto—even at 24mm. Also, when the Cactus is at full power, it’s equivalent to the Profoto firing at 8.4, approximately. As you can likely guess, especially if you’ve shot with flashes much, you can’t shoot with them at full power much at all without getting a ton of misfires. I prefer to keep my output at 1/4 power or lower to keep a fast refresh time.

This isn’t a big deal typically, especially when shooting indoors, because I can bump up my ISO a bit to allow for a smaller aperture without losing image quality. It only becomes an issue when you have a lot of ambient light that you need to overpower. That’s when having the more powerful Profotos would make your job much easier.

Let’s imagine that you are doing a shoot indoors with flashes and need a good amount of depth of field, meaning you need a smaller aperture. For example, I was recently shooting glass products on a white sweep, as you can see in the image above. I had three flashguns (two on the background and one into an umbrella on the product) all set to 1/4 power. By bumping up my ISO to 320 I was able to set my aperture at f/13, which allowed a deep depth of field. If I had needed an even smaller aperture, I would have felt comfortable going up to ISO 640 or even 800 with the 5D Mk III without losing image quality.

More often than needing more power when shooting product, I find myself needing smaller outputs, such as when I’m shooting with a large aperture in order to have a shallow depth of field in my shot. With flashes, I can easily dial down the power to 1/64 or even 1/128 in order to shoot at f/1.8, for example. If I were using studio strobes and wanted that large of an aperture, it’d be far more difficult. Even with the power pack dialed all the way down, I’d need to use a bleed light, which means plugging in an extra, unused light into my pack in order to pull additional power away from my light. My only other option would be to use a neutral density filter, which can result in a loss of image clarity.

Occasionally, using this minimal setup on larger shoots has bit me in the butt. Earlier this year I was doing a two-day commercial shoot for a national ad campaign for a big client. It was one of those situations where the client knew just enough to be dangerous but not enough to trust me. My contact looked at my minimal rig and said, “The last photographer had more lights. Tomorrow can you bring more lights?” I should’ve said, “But these go up to 11!”

The problem was not sufficient firepower, but rather proper client-photographer communication. I was shooting based on my typical workflow, which the client was unfamiliar with. Part of my workflow was to supply straight-out-of-the camera, small-resolution proofs immediately following the shoot, in order for the client to make selections for retouching. My contact for the client at the shoot was extremely happy with the images that first day, but when he forwarded the proofs to his boss in the evening, the response was less enthusiastic. The images were far too small and dark for print was the complaint.

This was when my contact asked me to bring more lights to the second day of the shoot, as the previous photographer had done. He went on to explain that the previous photographer shot everything for $1,000 and just gave them the raw files to edit. I did my best to not balk at this idea. I attempted to explain that I could light the images any way they liked and that these were just the preliminary, unedited proofs. They still weren’t convinced.

Finally, I color graded one image from each scenario and sent them, side by side with the original, to show how the final image would look. After seeing that the polished, final images weren’t, in fact, 800 pixels long and underexposed, they relaxed a bit. Needless to say, at the end of day two, I made sure to throw a quick preset on all the proofs to brighten them up, before sending them over to the client.

At that point, the industry stories I’d been hearing started to make sense: photographers bringing a whole van worth of lighting gear on high-budget shoots, knowing full well that they wouldn’t use most of it. Appearance, the theory goes, is everything. If the client is paying you big bucks, the client expects to see a big production.

I find this charade to be as cumbersome as it is deceptive, but I suppose that some people aren’t yet ready for change. Times are changing, nonetheless, whether the dinosaurs like it or not. It won’t be long before whole campaigns are shot with nothing more than a smartphone. But until then, on larger-budget shoots, I now play the part, renting out a large studio with large strobes to more effectively cater to clients’ large expectations.

If you enjoyed this post, check out Studio Anywhere 2, a new book that guides photographers in the art of shaping light using minimal gear.

About the author: Nick Fancher is a Columbus, Ohio-based portrait and commerce photographer. You can connect with him on Facebook here. You can also find more of his work and writing on his website and Instagram.