This 1940s Photo Was Made to Defy Hollywood Self-Censorship Rules

The Motion Picture Production Code, more commonly referred to as the Hays Code, was one of the most influential forces shaping Hollywood’s Golden Age. Created to uphold moral standards in cinema, the Code governed what could and could not be shown on screen for over three decades. Yet, as restrictive as it was, resistance to its rules surfaced even from within the industry itself.

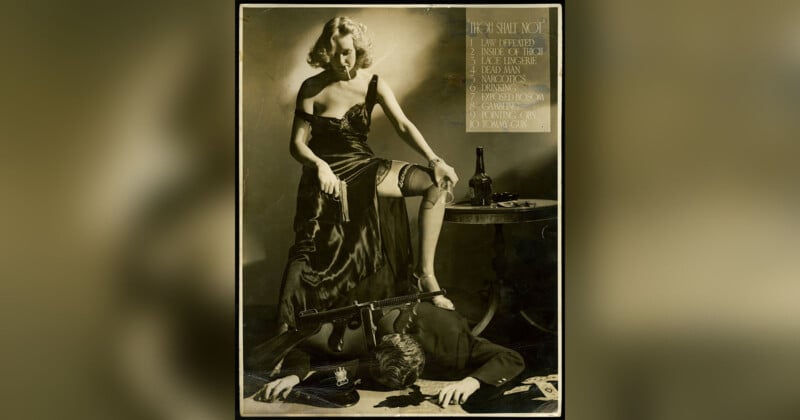

One striking example of this defiance came in the form of Thou Shalt Not, a 1940 photograph by Whitey Schafer that playfully but provocatively mocked Hollywood’s strict censorship guidelines. This act of subversion encapsulated the growing frustrations of filmmakers and artists who felt stifled by the rigid moral framework imposed upon them.

The Origins of the Hays Code

In the early 20th century, as cinema evolved into a major cultural force, its increasing influence alarmed conservative segments of American society. Silent films such as The Birth of a Nation (1915) and The Sheik (1921) demonstrated the medium’s power to shape public attitudes, while the growing popularity of talkies (films with dialogue) in the late 1920s further expanded Hollywood’s reach. However, the industry’s rapid growth was not without controversy.

Hollywood stars became icons of the Roaring Twenties, but their offscreen lives sometimes drew more attention than their films. The scandals of the 1920s, such as the trial of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle for manslaughter and allegations of murder surrounding the death of director William Desmond Taylor, tarnished the industry’s reputation. At the same time, films began pushing moral boundaries, featuring provocative themes such as infidelity, crime, and sexual liberation. These developments provoked a backlash from religious groups, women’s organizations, and politicians, who accused Hollywood of corrupting public morals and demanded stricter oversight of its content.

Fearing government intervention, the film industry moved to regulate itself. In 1922, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) was established under the leadership of Will H. Hays, a former Postmaster General with ties to the Presbyterian Church. Tasked with cleaning up Hollywood’s image, Hays sought to preempt censorship by creating a set of moral guidelines for filmmakers. The result was the Motion Picture Production Code — also known as the Hays Code — drafted in 1930 by Catholic layman Martin Quigley and Jesuit priest Father Daniel Lord.

The Code outlined specific rules about what could and could not appear in films, emphasizing upholding Christian values and promoting positive messages. Among its prohibitions were depictions of profanity, nudity, sexual relationships outside of marriage, drug use, and criminal behavior that went unpunished. However, during its first few years, the Code was largely ignored. Hollywood studios continued producing films with provocative or risqué content, resulting in what is now called the “pre-Code era.”

The Pre-Code Era and the Turning Point of 1934

From 1930 to 1934, Hollywood operated with minimal enforcement of the Production Code. This period saw the release of some of the most daring films of the early sound era. Movies like Red-Headed Woman (1932), starring Jean Harlow as a cunning seductress, and Baby Face (1933), in which Barbara Stanwyck’s character manipulates men through her sexuality, challenged traditional notions of morality. Filmmakers explored taboo subjects such as adultery, abortion, and the exploitation of women, often portraying these themes with startling frankness.

However, the permissiveness of the pre-Code era was short-lived. Religious groups, particularly the Catholic Church, became increasingly vocal in their condemnation of Hollywood. In 1934, the National Legion of Decency (also known as the Catholic League of Decency) was formed, organizing boycotts against films deemed morally objectionable. These boycotts proved to be highly effective, threatening the studios’ profits at a time when they were still recovering from the Great Depression.

Under mounting pressure, the MPPDA established the Production Code Administration (PCA) to enforce the Code with greater rigor. The PCA, led by devout Catholic Joseph Breen, could approve or reject films based on their adherence to the Code’s rules. Studios quickly fell in line, as releasing a film without PCA approval risked alienating theaters and audiences. The era of strict censorship had begun.

The Strictures of the Hays Code

Under Breen’s watchful eye, the Hays Code became a rigid system of moral oversight that governed nearly every aspect of Hollywood storytelling. The Code was revised numerous times over the years, but it rigidly adhered to three general principles:

- “No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime, wrongdoing, evil, or sin.”

- “Correct standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented.”

- “Law, natural or human, shall not be ridiculed, nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.”

The Code also included lists of words that could never be uttered in dialogue and carefully outlined how filmmakers could depict certain subjects. For example, “excessive and lustful kissing” and “sex relationships between the white and black races” were strictly forbidden. In some cases, the Code did allow the depiction of immoral behavior, but only if the film clearly condemned it.

Filmmakers often found these restrictions suffocating. Stories had to be carefully constructed to avoid explicit violations of the Code, leading to sanitized depictions of human relationships and morality. In some cases, pre-Code films were even remade in order to abide by the new rules. The now-classic John Huston (who would find himself clashing with Hollywood throughout his career) masterpiece The Maltese Falcon starring Humphrey Bogart — based on the 1931 film of the same name — was one such film.

At the same time, these limitations inspired a new kind of creativity, as directors found ingenious ways to suggest adult themes without directly portraying them. Double entendres, visual metaphors, and subtext became tools of the trade, allowing filmmakers to slip controversial ideas past the studio censors.

Thou Shalt Not: A Bold Act of Satire

By 1940, the Hays Code was firmly entrenched, and Hollywood’s artists were keenly aware of its impact on their work. While some found ways to thrive within its confines, others expressed their frustration in more overt ways. One such figure was Whitey Schafer, a Hollywood portrait photographer known for his playful and innovative style.

![]()

Schafer’s Thou Shalt Not emerged as a bold statement of resistance in an industry defined by censorship. The photograph, staged with a cast of actors and actresses, presented a humorous yet biting critique of the Hays Code’s moral policing. In the image, Schafer depicted a scene that flagrantly violated the Code’s guidelines — a sex worker smoking a cigarette while holding a gun, a dead police officer, and alcohol. The photo’s title is a playful jab at religiosity, and the plaque lists ten objects banned by the Hays Code — again, an obviously implicit dig at the Code’s deeply religious underpinnings.

While Thou Shalt Not was created as a satire, its subtext carried a deeper message about the creative constraints faced by Hollywood artists. Schafer’s photograph encapsulated the tension between art and censorship, calling attention to the absurdity of a system that sought to sanitize the human experience for the sake of public morality.

Cultural Impact and Early Resistance

The Hays Code was a reflection of the conservative social climate of its time, but it also helped shape that climate by reinforcing traditional values through cinema. By sanitizing films, the Code erased much of the complexity and diversity of human experiences. Topics such as racial inequality, LGBTQ+ relationships, and women’s autonomy were largely absent from mainstream Hollywood during the Code era, with only rare exceptions.

Yet resistance to the Code existed even in its early years. While Schafer’s Thou Shalt Not offered a humorous critique, filmmakers like Ernst Lubitsch and Alfred Hitchcock developed subtler ways to work around the restrictions. Lubitsch’s romantic comedies, such as Ninotchka (1939), relied on innuendo to explore adult relationships, while Hitchcock used visual tension and implication to hint at taboo subjects in films like Rebecca (1940).

![]()

These acts of defiance, whether overt or subtle, demonstrated the resilience of artists in the face of censorship. Though the Hays Code had succeeded in stifling many forms of creative expression, it could not wholly suppress the human impulse to question, challenge, and push boundaries.

The Cracks Begin to Show: The Decline of the Hays Code

By the late 1940s, Hollywood was facing a rapidly changing cultural landscape. World War II had left the world shaken, and the postwar era brought with it a desire for realism and stories that reflected the complexities of modern life. As the United States entered the 1950s, societal norms were evolving, and the rigid framework of the Hays Code began to feel increasingly outdated.

At the same time, Hollywood faced growing competition from international cinema. European filmmakers were not bound by the same restrictions, and their films often depicted sexuality, violence, and moral ambiguity with far greater frankness. Directors like Federico Fellini, Ingmar Bergman, and François Truffaut began to attract American audiences eager for something different, something that felt closer to their own lives and struggles. These films, which often explored themes deemed taboo by the Hays Code, exposed the limitations of Hollywood’s self-censorship.

![]()

Domestically, resistance to the Code grew stronger. Filmmakers began to test the boundaries of what could be shown on screen, often releasing films without the PCA’s approval. Otto Preminger was among the first to openly defy the Code, releasing films like The Moon Is Blue (1953) and The Man with the Golden Arm (1955) despite their rejection by the PCA. Both films were commercially successful, proving audiences were willing to embrace more provocative content.

The Supreme Court Steps In

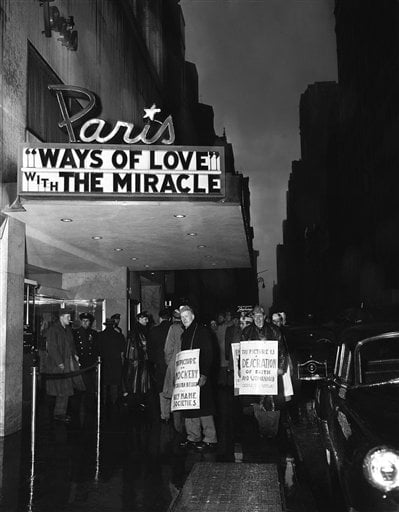

The final death knell for the Hays Code came from a series of legal battles. In 1952, distributor Joseph Burstyn released — or attempted to release — Robert Rosselini’s “anti-Catholic” short film The Miracle (the second episode of a collaboration between Fellini and Rosselini titled L’amore) in New York City. Protests worldwide condemned the film as blasphemy, and the New York State Board of Regents declared it “sacrilege” and revoked its license. Burstyn took the issue to court, eventually appealing to the Supreme Court, where he argued that film is an artistic medium protected by the First Amendment.

In the landmark 1952 case Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Hollywood’s censorship was a “restraint on freedom of speech.” This decision overturned earlier rulings that had excluded films from free speech protections, effectively undermining the legitimacy of the Hays Code as a tool for regulating content.

The Court — under Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson — declared that the “Miracle Case” was “the first to present squarely to [them] the question whether motion pictures are within the ambit of protection which the First Amendment, through the Fourteenth, secures to any form of ‘speech’ or ‘the press.’’’ The Court further held “It cannot be doubted that motion pictures are a significant medium for the communication of ideas’’ and movies ‘‘may affect public attitudes and behavior in a variety of ways, ranging from direct espousal of a political or social doctrine to the subtle shaping of thought which characterizes all artistic expression. The Court further recognized movies “as an organ of public opinion is not lessened by the fact that they are designed to entertain as well as to inform.” Motion pictures, the Court decreed, are “a form of expression whose liberty is safeguarded by the First Amendment.”

As the 1960s progressed, the social upheavals of the Civil Rights Movement, the feminist movement, and the sexual revolution further eroded the cultural foundations upon which the Hays Code was built. The countercultural ethos of the decade celebrated rebellion, authenticity, and the breaking of taboos — values that were fundamentally at odds with the sanitized moral universe of Code-era Hollywood.

By 1968, the Hays Code had become irrelevant. The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), recognizing the need for a new system, introduced the modern film rating system (though that, too, would undergo some adjustments over time). This system, which categorized films based on their suitability for different age groups, allowed filmmakers far greater creative freedom while giving audiences the ability to make informed viewing choices.

The Legacy of Thou Shalt Not

In retrospect, Whitey Schafer’s Thou Shalt Not feels like a prophecy, a playful yet pointed critique of a system that would ultimately collapse under its own weight. While the photograph was not a widely publicized act of rebellion, it has since gained recognition as a symbol of resistance to censorship in Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Thou Shalt Not holds a unique place in the history of Hollywood’s struggle with self-censorship. Schafer’s satire captured the absurdity of the Hays Code in a way that words alone could not. By exaggerating the Code’s restrictions and turning them into a visual checklist of “immoral” behaviors, the photograph laid bare the contradictions and hypocrisies of a system that sought to dictate morality through art.

But beyond its critique of the Hays Code, Thou Shalt Not also serves as a broader commentary on the relationship between art and authority. In any medium, the imposition of strict rules inevitably creates friction as artists push back against constraints that stifle their creativity. Schafer’s photograph reminds us that art thrives on freedom and that attempts to control it often inspire acts of rebellion as powerful as the rules they defy.