Fujifilm Opens Up About AI, 8K Video, Entry-Level Cameras, and More

![]()

While attending the CP+ 2023 show in Yokohama earlier this year, I met with representatives of Fujifilm and had a chance to ask them about the reasons behind some camera features, the details of a recent firmware update, specifics about some of their future plans, and some more philosophical questions about 8K video and whether there’s still a place for “entry-level” models in the industry these days.

I’ve tried to identify each of the speakers in the interview below based on their voices and notes I made at the time, but apologies in advance for any misattribution I might have made.

Let’s dive in, and let me know any questions or added thoughts you might have in the comments at the end. As usual, comments or editorial notes I made in transcribing the conversation are set in italics.

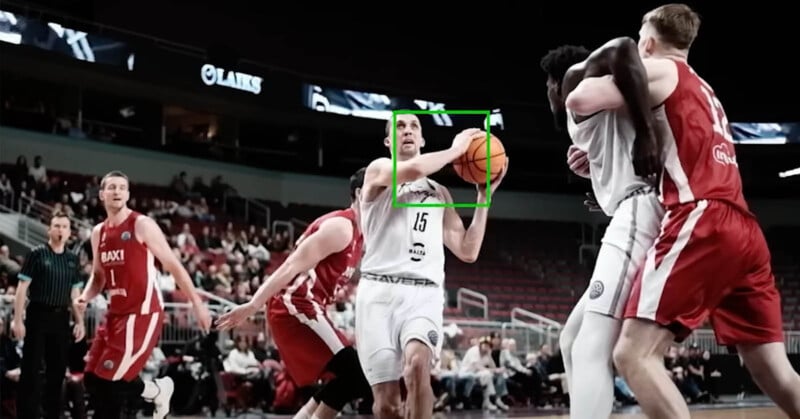

What Does It Take to Update AI Subject Recognition Algorithms?

David Etchells: One thing that’s great about Fujifilm is you continue to develop the firmware and support existing products over the long term. Just recently, firmware 3.0 for the X-H2S also improved recognition for subjects under difficult lighting and for subjects that are facing sideways or small in the frame as well. What’s the process like for expanding the coverage and accuracy of deep-learning subject recognition algorithms like this? Does it require gathering thousands more images to create a larger training set, or are there ways you can modify existing training images to make the job easier?

Jun Watanabe: We keep running the training, and in some areas we replaced the dictionary and in some areas we added to it.

DE: So some of it you can modify, and some of it you have to add. I’d imagine that things like a smaller subject in the frame are just a modification, but sideways-facing requires a new image entirely.

JW: Yes, we have iterated it higher than the previous version.

DE: That seems like such a large task to me; to assemble the training set, you need *so* many images. Is that kind of a continuous process then, that whoever is the engineer working on that, they just constantly add new elements to the training database?

JW: Yes, it’s continuous.

The whole process of training an AI system to consistently recognize photographic subjects and precisely locate them within the frame seems like a massive undertaking to me.

First, you have to come up with many thousands of images of each kind of subject you want to train for, including all manner of likely variations between individual subjects, as well as lighting, color balance, etc, etc. You can make your image database work a little harder for you by creating different versions of the base images with the key subjects larger or smaller in the frame, and in different locations within it.

But then a human has to go through all the images and tag the critical elements within them. (As in “Here’s a human, here’s the body, here’s the face, here are the eyes. Here’s another human in the same image.” On and on for thousands of images.

Then you have to evaluate how well the system is working by running it on thousands of *other* images, with a human checking the results to see if it correctly identified and located all the subjects. If it didn’t work as hoped, you need to go out and find yet more images to fill in the gaps you think you’ve found in its knowledge base. Do you want it to be able to recognize humans when they’re turned partially away from the camera? Go find a few thousand examples of that sort of photo, have humans tag them, and then re-train the model. Rinse and repeat.

From Watanabe-san’s answers above, it seems that sometimes they can just add images to the database and update the neural-net weights, but other times they have to throw out the existing model and feed everything back into the AI all over again.

I have to say that I’m impressed that camera manufacturers have been able to keep up with cell phone makers in this critical area as well as they have. Companies like Apple and Samsung have R&D budgets in the billions of dollars, and while those budgets are spread across every aspect of smartphone technology, just the portion they devote to imaging must dwarf the resources of any camera maker out there.

Camera manufacturers like Fujifilm do have the advantage of decades of history addressing the needs of photographers. The issue of figuring out what’s the subject and what’s not is actually one that camera makers have been dealing with for years now, just not with AI. These days the challenge is figuring out where the subject is and focusing on it, but in times past they had to solve the same problem not only for setting focus but for the sake of determining the proper exposure as well. Camera makers have for decades maintained enormous libraries of photos that they used to develop their exposure algorithms with. Now, I suspect many of those same database images are being used for training subject recognition AI systems.

What Did You Do to Speed Up AF Tracking in Firmware 3.0?

DE: A third improvement in Firmware 3.0 was to improve AF tracking of fast-moving subjects. What did that development process look like? That is, what sort of changes did you need to make to implement this, and what were the challenges that had to be overcome that prevented the camera from having that capability from the beginning?

JW: We have two new major improvements. The first is strictly matching the subject detection result and the AF area. This supported the focusing even when the subject moves very fast. The second one is that we increased the AF frequency during continuous shooting. Those two major things were what improved the performance. And the photographers have well-accepted the performance we achieved.

DE: It’s interesting you’ve increased the focus cycle frequency. Is it a matter of taking the data off the sensor faster or just that you can complete the processing more quickly?

JW: It’s the processing.

DE: So you just made the algorithms more efficient so they could complete their work faster.

JW: Roughly double the speed.

This was very surprising to me, that they could DOUBLE the AF processing speed just by tweaking the algorithms. I’d have thought such speed improvements would need faster hardware.

AI Subject Detection and PDAF Together for the First Time

DE: It’s very interesting that you’ve coupled the subject detection with the phase-detect AF system. I think that’s been a challenge; with some companies I know they’re entirely separate things, so if you’re using subject detection, you lose your tracking speed. That’s really significant. Fujifilm has always really … focused

This was an observation I made during the discussion rather than a question, so it didn’t lead to a direct answer. I wanted to highlight it here though, because I think it’s a very significant development. As I mentioned, subject detection is an entirely separate process from normal autofocus, relying solely on 2D image information to find and focus on the subject. When the AI algorithm locates a subject within the frame, it then tells the phase-detect AF system which focus point(s) to use, the AF system determines the subject distance and commands the lens to move, the lens makes the focus adjustment, and the shutter fires. Each frame is like an entirely separate shot, made without any knowledge of the subject’s motion.

By comparison, conventional AF uses the continuously-updated distance information from the phase-detect AF points to find and track the subject. This lets it predict where the subject will be in the next frame and keep the focus moving in the right direction, even while its view of the subject is interrupted when a picture is taken. When the AF system can see the subject once again, chances are that the lens will already be very close to the correct focus, so the shutter can fire as soon as it’s ready, without waiting for the lens to catch up.

The big advancement in the X-H2S’s version 3.0 firmware update is to tightly couple the AI and conventional parts of the AF system, getting the best of both worlds. The AI system makes sure the phase-detect system knows exactly where in the frame the subject is located, but the latter can still use its continuously updated distance information to follow the subject’s motion.

Subject Detection and AF Improvements Coming to the X-H2?

DE: To what extent will the firmware improvements seen in the X-H2S become available to older or lower-end models, or do they exclusively require the high-speed sensor readout of the X-H2S? Will the X-H2 get the improved subject recognition algorithms in a forthcoming firmware update? Does the X-T5 already have those algorithms implemented in it?

JW: This algorithm isn’t limited to the X-H2S, so we can technically apply it to the other fifth-generation products. So we would like to consider expanding its higher performance to other models.

DE: So other models may not be able to be quite as fast as the X-H2S, but you’ll be able to make similar improvements relative to their current performance.

JW: In terms of the algorithms, yes.

DE: Does the X-T5 already have the algorithms in it that were in Firmware 3 for the X-H2S?

JW: No.

DE: Ah, so that might come at some point then.

This is clearly very good news for X-H2 and possibly X-T5 owners as well. While sensor readout in the X-H2S is much faster than in the X-H2, the new tracking algorithms are twice as efficient once the data is in the processor. This means that a firmware update to the X-H2 could bring a similar relative increase in tracking speed for that model as we’ve just seen in the X-H2S. Fujifilm has an excellent history of continuing to support their cameras after initial releases, with many models receiving multiple firmware updates.

Why No Battery Grip for the X-T5?

DE: I’ve heard some complaints about the X-T5 not having a battery grip option. The X-T4 had one, why not the X-T5?

JW: The concept was to go back to the origin, and that concept was to be small and lightweight with high image quality. Within this concept, we were able to achieve a battery life of 740 frames, which is more than X-T1 with the grip. So this time, we focused on the original concept, and because [we didn’t design it to accept] a battery grip we could achieve a smaller size.

DE: Ah, I see. So the basic frame would have to be bigger just to allow the attachment of a grip?

JW: Yes, especially the height. Another 3 millimeters taller. So since you can shoot more images with just the internal battery, we didn’t see a need for the grip. If the user wants to use a battery grip, we point them to the X-H2, the more professional model we have.

DE: Ah, so basically if you want the larger form factor that a battery grip would require, look to the X-H2 models. You’ve separated the markets a little bit, and the X-T5 is as you say, going back more to the original concept and is more compact.

This is something that hadn’t occurred to me, namely that the body of a camera has to be designed to be able to couple to and support a battery grip, and that doing so may increase its size. The original concept of the X-T[x] series was for them to be powerful, compact cameras, with “compact” being a key goal. The X-T5’s battery life is so good that very few people would need to extend it with a battery grip, so the designers chose to forego it and trim about 3mm off the body’s height.

![]()

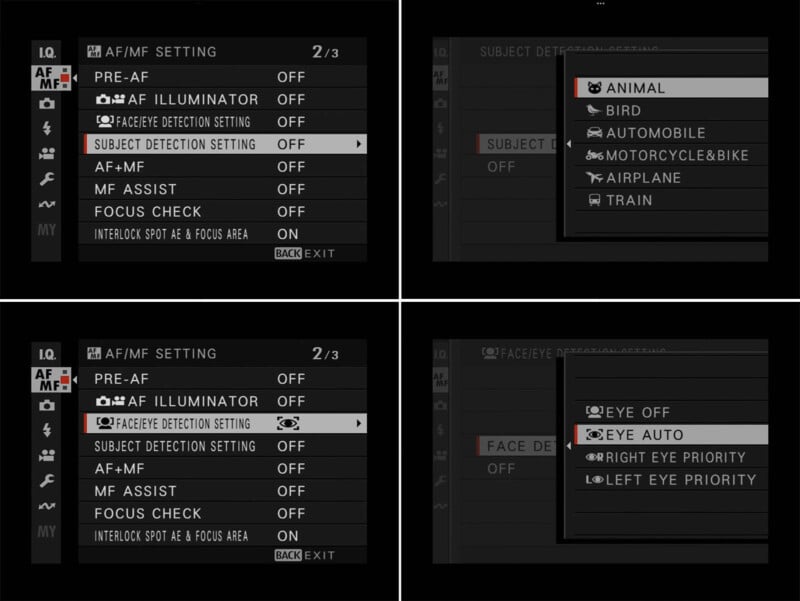

Why the Change in the X-T5’s Autofocus UI?

DE: This is a user interface question that I’ve picked up from discussions online. Some people feel that there’s a bit of a disconnect in the X-T5’s autofocus system, in that the face- and eye-detect modes are now separated in the user interface from the AI-based subject detection modes. Why is that, and could all the subject-related AF modes be brought together in the interface in the future?

JW: We focused on providing the same operation of face and eye detection, so we separated them from subject detection.

Yujiro “Yuji” Igarashi: Meaning compared to the previous models.

JW: Yeah, compared to the X-T4, etc. But since we launched the X-H2S, we’ve gotten so much feedback from the users that we are now considering how to improve the usability based on what we’ve heard from the users.

DE: So you’re studying the possibility of a UI change via the firmware? I think people will be happy to hear that, and again it’s great that you take the feedback from users and respond to it. You’d think that all the manufacturers would do that, but somehow it’s not necessarily common – at least to the extent that Fujifilm seems to do it.

I’m sure all manufacturers listen to user feedback, but Fujifilm seems to take it to heart more than most. I don’t know whether the X-T5’s user interface will change in some future firmware update, but you can see the impact of user feedback in the long history of prior firmware updates across their whole product line.

Where Does 8K Video Fit In?

DE: I have kind of a general question about 8K video and where it really fits. I can see professionals shooting on 8K for re-cropping or downsampling to 4K. But even high-end or enthusiast consumers – I don’t see that being a market at all. Who do you see as being the users for 8K? Production values on YouTube have gone way up in recent years, so are high-level YouTube creators using 8K in similar ways to pro videographers? Or maybe professionals outside of video production companies, perhaps wedding photographers are shooting 8K? Where do you see the market for 8K video capture, and how large a segment do you think it is?

YI: Maybe in the future. I think it’s still early-stage, but we do see some 8K usage. But it’s an aspect of future-proofing.

DE: Ah, there’s some usage now, but it’s more about future-proofing your line against what will be coming.

(Notably, as far as I know, the X-H2 was the first APS-C camera with 8K capture.)

This matches what I heard from other manufacturers. I came into these interviews not understanding why 8K seemed to be such a big checkbox on feature lists. Who really needs it these days? Sure, I guess people wanting to crop into the frame and still end up with 4K output might care about it, but *dang*, 8K video files are enormous, and how many people really care about maintaining full 4K resolution even after cropping their footage by 50%?

As Igarashi-san noted though, it’s ultimately about future-proofing. 8K files are a pain to edit (although considerably less so now, thanks to Apple’s M1 and M2 chips and AMD’s EPYC series of CPUs), but technology marches on, and 8K won’t be much hassle to work with in just another year or two. So it makes sense to look for 8K capability in a camera that you want to last you for a few years.

(For what it’s worth, while 8K source footage is certainly useful if you want to crop down to 4K resolution, I don’t think 8K will ever make much sense for final output. People with perfect 20/20 vision can resolve 7,680 x 4,320 pixels (33 megapixels) if the subject is moving and they’re at a close enough viewing distance, but for the vast majority of people sitting at typical TV viewing distances, there’s virtually no difference between 4K and 8K content. Interestingly, even people with perfect 20/20 vision can only resolve about 4K for still images. Even the sharpest eyes can only see 8K or higher detail if their gaze is moving.)

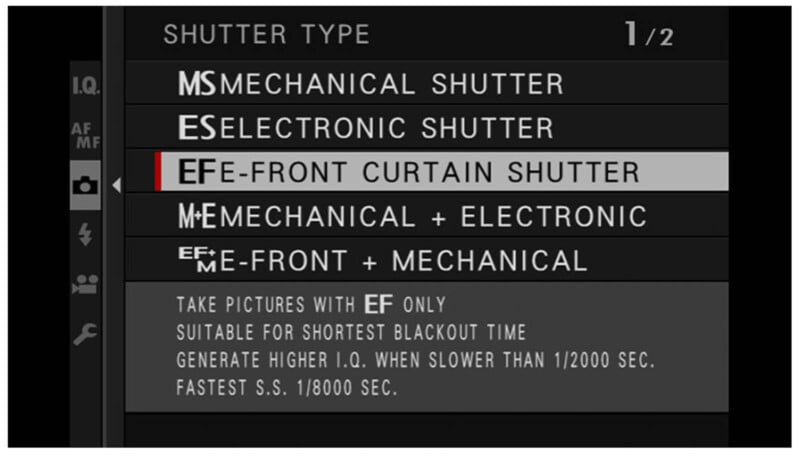

A Tweaky Technical Question About Mechanical Vs Electronic Shutter

DE: This is another of the minor technical points I tend to ask about, but I don’t think I’ve inquired about it before. I notice that the X-H2 can shoot full-frame images continuously faster when using its mechanical shutter than with the e-shutter. That seems a little counter-intuitive, and I’m wondering why this is the case.

JW: This is because with electronic shutter shooting, continuous shooting must be carried out at the same time as the real-time view is being displayed. So at 40 megapixels, the rate is 13fps. But with the mechanical shutter, the highest speed is 15 fps, because when you’re shooting with the mechanical shutter blackout, the post-view image is displayed. That’s the difference.

In the beginning, “post-view display” is how all mirrorless cameras worked. It means that the viewfinder shows the image that was just shot, rather than what’s happening in front of the lens in real-time. This “viewfinder lag” made tracking fast-moving subjects difficult with early mirrorless models. Current Fujifilm cameras like the X-H2 update the viewfinder with almost zero lag and no blackout, but that means they have to maintain two completely separate streams of data off of the sensor. Shooting with the mechanical shutter only needs a single data stream, so the camera can hit 15fps in that mode.

Is Subject Recognition Tied to Exposure? Could It Be in the Future?

DE: Does subject recognition tie in at all to exposure determination, and if not, could it be made to do so in the future? I’ve read comments by users struggling with situations where they’re using subject recognition to focus on a white bird standing in the shade, and when it suddenly takes off and flies into the sunlight it becomes grossly overexposed. Would the processor architecture support linking subject recognition with the exposure system? Might we see that happen in the future, via a firmware update?

JW: Currently the subject-detection results are only linked to exposure for human faces. It’s not currently supported with animals though, because of the variety of colors and the difficulty of knowing what the exposure should be. We’ll consider how subject detection should develop in the future though, by listening to users’ comments and feedback.

DE: So there’s a link to exposure with humans,, because you know what humans look like. But with animals, you don’t know ahead of time whether the bird is supposed to be white or gray or whatever. The camera is only aware that there’s a subject that’s separated from the background in a certain way.

This was a very interesting point: Humans’ shape and coloring are consistent. There’s of course a wide range of skin tones, but people don’t have mottled tones or bright colors on their faces, so the camera knows how to set the exposure when it detects a person’s face. With wildlife, though, even if the camera is able to find and focus on the subject’s eyes, it doesn’t have any idea what color the animal’s face is, so it can’t use it to set the exposure the way it can with people.

It might be possible in the future for cameras to figure out what color the subject is by analyzing contrast and tone across the frame, but it’s clearly a much more difficult problem than dealing with humans, where the camera knows what they look like. More to look forward to…

Is There Still a Place for “Entry Level” Cameras?

DE: I’ve been thinking a lot lately about “entry-level” and what that means these days. On the one hand, the market for entry-level cameras is going away because phones do so much, but on the other hand, it’s expensive for someone to be able to get into a camera platform in the first place. Fujifilm has never been about aiming for low-cost/low-value products, but currently the cheapest body for someone to get into your system costs $850 (the X-E4), and you don’t seem to have a product aimed specifically at vloggers/Youtubers. This means it costs at least $200 more for a user to get into the X-system than some of your competitors. Do you see a need for a lower-cost model at some point, to serve as an entry point to your system?

YI: Yeah, I think there’s potential there, but it’s a matter of the performance vs cost, if that makes sense. If we were to introduce such a product, we’d of course need to make sure that the image quality was good enough and the performance was good enough. We have a level of performance that we believe will satisfy customers, and the cost to develop that means that we can’t achieve a very low price point. So there could be some solution, or there could be some demand for a certain level of image quality, etc, but we need to figure that out.

DE: Yeah, that makes sense; you don’t want to just make a cheap camera and give people a bad experience.

YI: Yes, exactly.

DE: The point would be to encourage them to continue on in the line.

YI: Yeah, the last thing we want them to decide is that their smartphone is better.

This is consistent with what I heard from essentially all the manufacturers. Smartphones have basically eliminated the market for entry-level cameras. A $300 interchangeable-lens camera with poor/slow autofocus and mediocre image quality wouldn’t be a bargain for anyone and would likely turn off more users than it would attract.

I think that used cameras are probably serving the same function as entry-level models did in the early days. Digital cameras have been around for decades now, and a 5-year-old model in good condition is actually a very good camera. It might feel a bit more risky for a beginner to buy a used camera vs a brand new one, but there are plenty of reputable used-equipment dealers out there if you’re not willing to take a chance on eBay. I do think it would be good for the industry if there were brand new entry-level models available, but the points that Igarashi-san makes are valid. Smartphones have raised the bar on user expectations for cameras, and cheap models that fell short on image quality or capabilities wouldn’t do anyone any favors.

What’s Next? Some Hints…

DE: So 2022 was an incredibly productive year for the Fujifilm system, especially the X-series, and 2021 was even more so, with several key releases for the GF lineup as well. While I know you can’t comment on any specific product plans, how would you characterize your strategy for 2023 and beyond? What sort of products (both bodies and lenses) do you see being most in demand from your customers?

(Maybe that’s a sneaky way of asking what you’re going to do next.

YI: Yes, yes. Like you said, last year was an X-series year, the year before that was GFX. So you know, of course we continue to invest in both. That’s the best strategy to have, to have two strong series.

DE: So you tend to alternate a little bit, so this year might be a bit more GF-focused…

YI: Ah, we can’t comment on that

DE: Yeah, we can observe that there’s been a bit of a pattern, but we can’t draw any direct conclusions from it…

YI: Yeah, we are always looking into what’s lacking in our lineup and where we can enhance for each series. For GFX series, X series, whatever. So we’re always looking into new technologies that are available, and how we can adapt them to our camera systems, how we can bring benefits to our end users.

Makoto Oishi: We want to expand our photographic field further and further.

DE: So broadening the range of use cases or opportunities. Ah, interesting. Now I need to figure out what that means…

This was interesting, as it’s the closest I’ve heard a manufacturer come to actually saying what’s coming next. (I never get a solid answer to questions like this, but have to keep asking them for the sake of our readers.) Without QUITE saying it directly, it seems that 2023 is going to see more action in the GFX line than the X-series.

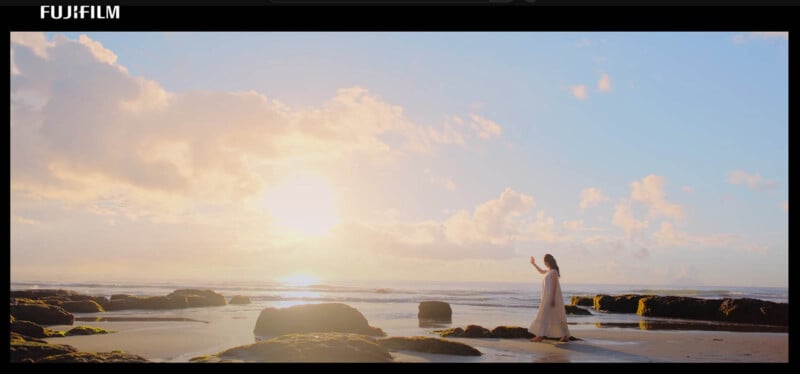

Why Not AI for Image Adjustment, vs Just Subject Recognition?

DE: This is a question I’m asking all the manufacturers: In the camera market, we’re seeing AI-based algorithms used for subject recognition, and to some extent scene recognition, but not for influencing the actual content or character of the images themselves. I’d characterize all these as “capture aids”, in that they more or less assist the photographer with the mechanics of getting the images they want, but don’t affect the images themselves. (HDR capture being an exception.) In contrast, smartphone makers have used extensive machine learning-based image manipulation, strongly adjusting image tone, color, and even focus in applications like night shots, portraits (adjusting skin tones in particular), and general white balance. I think it’s going to be critical for traditional camera makers to meet the image quality (or perhaps more accurately “image appeal”) offered by the phone makers. This feels like a distinct disadvantage for the camera manufacturers in the competition with smartphones. What can you say about Fujifilm’s strategy and work in this area?

YI: Yes, so this is a very interesting question, and you know, we’ve always discussed it internally as well. What do people want from cameras? Why do they buy cameras vs smartphones? I think you’re right that maybe some people want that kind of feature on their camera, but I think at the same time it’s important for us that we have an image that is very clean. Because of course for editing in post-production, you can do anything, right? As long as the original image is very clean and has the best image quality. So I think that’s fundamental for the digital camera, what’s important. And I think that although the trend is changing and we have to look toward the future, I think you’re right about that trend. But for us, we don’t think cell phone users want to buy our cameras to do the same thing in the camera as in their phones. So for us, the clean image, the basic image quality is at the core. Then we have the film simulations and we believe the reason that feature has been popular is because it’s been consistent and it has a history from the film days. This is the Velvia look, or this is the Provia look. And that still continues in our digital cameras. So when people use our color, it’s more tangible or real, something that’s not fake. That’s what people think, it’s more emotional. I think that’s very important in terms of our direction with regard to color. So that’s the base we have, and then of course we will also have to think about what is the future, what else we can add. But that’s basically our thinking.

DE: Yeah. With the film simulations, the camera is creating a different version or different rendering of the original, but it’s consistent, you’ll always know how it’s going to behave, as opposed to… you point a phone at something and you’re not quite sure what it’s going to do. I mean, if the phone creators did a good job, it’s going to make a pleasing image, but you don’t know exactly how it’s going to get there.

I think some of this question comes out of my own frustration, in that sometimes … I mean I’m a photographer (albeit not a very good one), and I like to use cameras and take pictures with them. But sometimes it’s more effort with a camera. I mean I can do whatever I want in Photoshop, but sometimes I’d like the camera to help a little with whatever – you know, with the exposure or tonal range or perhaps the white balance. It’s interesting, in that I tend to think of it more in terms of exposure within the scene as opposed to the overall color rendering. – Because as you say, I think your guys’ color is the best in the business.

YI: Yeah, so we don’t want people to think of our color as “fake color” in any way. It’s more than that, with all the color science we have. I think it’s a fine line between that and if we, you know, fiddle around with the color vs how we scientifically analyze the color.

DE: Yeah, I guess my pain point has more to do with the exposure within the frame rather than the color issue. But of course the cellphone manufacturers are manipulating everything. It’s kind of interesting because I see people asking, well “do you want the Apple look or the Samsung look”. – But also the Apple or Samsung look could change significantly from one generation to the next. I guess my ideal would be if the camera could even save, say an “undisturbed” JPEG (it’s kind of funny thinking of a JPEG as some sort of a RAW format), and then one that the camera had some influence over. And if I could just dial it up or down, you know like I want the camera to do its thing, but maybe -2 or +1 or something like that.

YI: Yeah, I agree about the GUI and how easy you know you can manipulate it. I think there are things there we can learn from.

DE: I guess I can sum up your comments by saying that it’s a moving target, with constant change in people’s use cases and expectations, and you’re obviously looking at the whole question of how to deliver what the customer is looking for.

Fujifilm’s response here generally falls in line with what I heard from most other manufacturers: They view their job to be delivering a “clean” image that the photographer can then manipulate however they like, rather than having the camera do a lot of manipulation or adjustment. In some ways, I can understand this more with Fujifilm, because color and color rendering are such an integral part of what their camera systems are about.

Good color rendering is of course something that every camera manufacturer cares about, but Fujifilm is in a bit of a unique position, thanks to their very successful film simulations. The “looks” of various classic films are complex combinations of contrast, tone, and color. Any AI-driven manipulation of the image content could easily destroy that. Even a little AI-based tweaking would result in a Velvia, Provia, or ACROS simulation that didn’t look anything like the original film emulsion.

Overall, it’s a delicate balancing act, to let AI “help out” with difficult subjects and lighting without taking control away from the photographer. I do think we’ll see some implementation of AI-based image enhancement in cameras going forward, as it could potentially save a lot of post-capture time in Photoshop if it’s done well. – But this conversation more than others made me realize just how tricky it will be for camera makers to on the one hand make it easier for photographers to deal with difficult subjects, while at the same time not take away the very reason people want to use a camera vs a smartphone.

Is There Any Crossover Between Instax and Your Digital Cameras?

DE: For my last question, among all the camera manufacturers, you’re kind of unique in that you have a connection to the analog world, with your Instax (instant-photo) lineup, which has been wildly popular. Do you view Instax users as likely prospects to eventually become X-series users as well, or are the two markets fundamentally separate?

YI: [There was a bit of back and forth here, so the following is a summary of Igarashi-san’s comments.] Perhaps. The mini Evo Instax model has almost an X-series look, so maybe there’s some attraction from that design. Then there are also the film simulations which we just talked about – there’s a resurgence of film and that look is very popular and so there could be something there as well. You know, we always look at our imaging customers and the potential for each customer to be interested in other product offerings as well. So generally I do think that there’s potential, as long as they’re interested in imaging.

DE: Yeah, so much of the instant photo market is about almost “disposable” images, which is kind of contrary to the camera user’s motivation. But it just struck me that that’s a very unique aspect of Fujifilm, that you have a very strong analog connection – and of course with your film stock too. It’s interesting to me the extent to which film seems to be growing again. The film business… Ricoh doesn’t have a presence at this show but I’ll be meeting with them next week, and it’s interesting that they’re actually looking at bringing out new film cameras again. (I guess in that case it would be great if Ricoh could bring out a new camera and Fujifilm could make money from it.

I admit that I wasn’t actually expecting there to be a lot of crossover between INSTAX and Fujifilm’s digital camera products; instant prints and digital cameras have very different user bases and use cases. I did still wonder though, if there might be some cross-interest between the markets, given that no other camera maker has such strong footing in both the analog and digital worlds.

It does seem like it’s a bit of a stretch, but the surprise for me was that Fujifilm’s Evo Mini INSTAX camera actually offers film simulations as well. They’re named differently because classic film names would have little meaning for the typical INSTAX user. But the basic functionality is there, and I can see the aesthetic appeal, even for users who have no idea what Provia or Velvia might be.

DE: That’s actually all my questions, we went through them very quickly this time. Thanks so much for your time!

All: Thank you!

A Summary of the Interview

Phew, that covered a lot of ground! Here are some quick bullet points to summarize it:

- Fujifilm’s engineers are more or less continuously updating their AI-based subject recognition. A lot of times they can just train the AI on new images incrementally, but other times they need to rerun training for the entire database. In any case, adding new images to the database is very labor-intensive, because at some point a human has to manually tag the relevant subject(s) in every image.

- Firmware version 3.0 for the X-H2S speeded up AF tracking by almost 2x and did so simply by making the algorithms more efficient. This same relative increase in efficiency could come to the X-H2 and X-T5 at some point, in future firmware updates for those cameras.

- In what I think might be a first among camera makers, Fujifilm’s latest firmware now tightly couples AI subject recognition with conventional phase-detect-based AF tracking. This is significant because AI subject recognition and conventional AF tracking are two fundamentally different processes. Getting the two to work together in close coordination is a big breakthrough.

- The X-T5 didn’t get a battery grip because its battery life was so good without it. The original concept for the X-T series was for them to be compact, powerful bodies. The greatly improved battery life resulting from its next-generation processor means that the vast majority of users won’t need the accessory grip to get the battery life they’d like, and importantly, eliminating the battery grip option lets the engineers shave 3mm off the camera’s height. For users who want a grip for ergonomic reasons, the X-H2/H2S provide that option.

- Some users have complained about the change in how face- and eye-detect AF have been separated in the X-T5’s user interface from the AI-based subject detection modes (as was also the case with the X-H2S). Fujifilm’s heard these concerns, and are studying the possibility of changing the firmware to accommodate these user requests.

- I asked a number of manufacturers about 8K video, and whether there was really a strong use case for it presently. Fujifilm’s answer matched others, saying that it was important future-proofing for their customers.

- I was puzzled by the fact that the X-H2 can shoot faster with a mechanical shutter than with an electronic one. It turns out that’s because it doesn’t have to maintain a no-blackout live view display when using the mechanical shutter, so it doesn’t have as much processing to do for each shot in that case.

- I asked if exposure could be tied to subject recognition, so a white bird flying from shadow into sunlight would be properly exposed. It turns out this would be difficult because the camera doesn’t know ahead of time what color the subject is – as opposed to human faces, which have a consistent tonal range.

- As with other manufacturers this trip, I also asked Fujifilm if there’s still a place for true “entry-level” cameras. The bottom line is that stripping out features and performance just to hit a price point would produce a disappointing user experience. This would defeat the purpose of convincing new camera users to adopt the Fujifilm platform.

- What’s coming next, in 2023? It wasn’t an unequivocal answer, but they did note that there’s something of an every-other-year cadence between the X series and the GFX models. The number of significant X-series announcements we saw in 2022 naturally suggests that we’ll likely see more activity on the GFX front in 2023. (Note: Fuji recently quietly cut the price of the original GFX100 body by $3,500. It’s a safe bet that there’s a new GFX model about to drop…)

- I also asked Fujifilm the same question as I did other manufacturers about using AI for image adjustment, not just subject recognition. I got much the same answer as from other companies (it doesn’t fit what they see as their mandate as a camera maker), but in the case of Fuji, the fact that people look to them so strongly for specific color and tonal renderings (in the form of their film simulations) makes AI-based image manipulation even more antithetical to the reason people are attracted to their brand in the first place.

- I wondered if there might be some user crossover between Fujifilm’s INSTAX instant-print camera line and their digital cameras. It seems like the two customer bases are fairly distinct, but the fact that their Mini Evo model supports a consumer-level version of their film simulations perhaps suggests some crossover interest.

As always, it was an interesting and illuminating discussion; many thanks to the participants for sharing their time so generously with me!