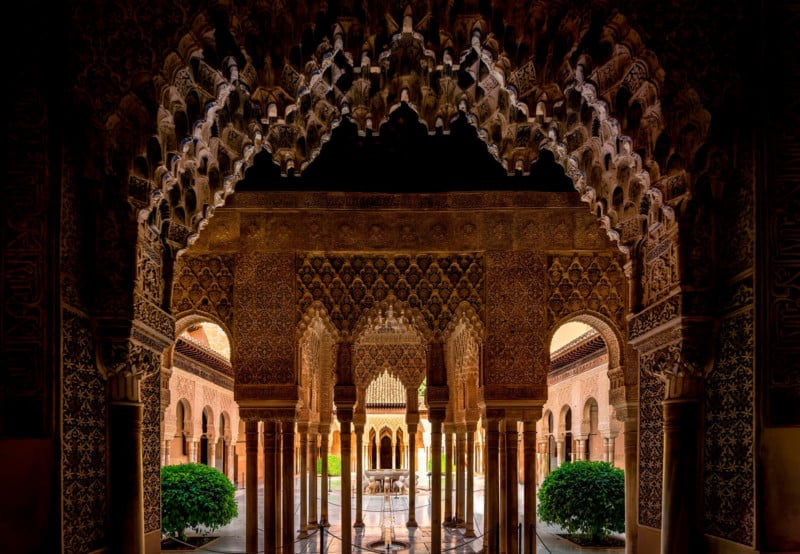

Red Castle: A Photographer’s View of the Iconic Alhambra in Spain

Transcendental. Whether seen on its perch on Granada’s Sabika hill against a backdrop of the Sierra Nevada or from the inside, where 13th- and 14th-century Muslim artisans, using the most advanced techniques of their time, fashioned an interior so surreal, it leaves the mind disoriented.

In the 12th century, with Muslim power in al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) in decline, a minor but ambitious local strongman by the name of Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr ibn al-Ahmar founded an emirate in Granada that became the last Muslim bastion in Spain and set off a golden age that lasted for three centuries. It was his descendants – the Nasrid sultans – who took it upon themselves to build a fortified palace complex that was then, and now, one of the finest buildings in all of Europe.

The elegant and graceful ‘Generalife’ garden complex – part of the sultan’s summer estate – was meant to evoke heaven on Earth. ‘Generalife’ is from the Arabic jannat al- ‘arif meaning ‘the Master’s paradise’.

Forbidden by Islam to depict the human form, Muslim architects and craftsmen perfected the art of doing more with less, relying instead on geometry, symmetry, and play of light and shadow to signal the presence of Divine Order in their creations. And nowhere is this more evident than in the Alhambra.

The Alhambra was not just a summer estate – it served an important function as a fort, as evidenced by the presence of the Alcazaba (Arabic ‘al-qasaba’ or ‘fortification’) on its western tip.

Granada’s Muslim era ended in 1492, decline set in, and the Alhambra was forgotten. It wasn’t until the 19th century that it returned to the public imagination, mostly through the efforts of American writer Washington Irving.

(The Sabika was) the crown on the forehead of Granada, and the Alhambra (May God safeguard it!), the ruby at the peak of the crown. –14th century poet, Ibn Zarmak

About the author: Talha Najeeb is a self-taught landscape, travel, and street photographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Najeeb’s work on his website, Flickr, and Twitter. This article was also published here.