The Homeless Photojournalist Who Lends His Eyes to the World

![]()

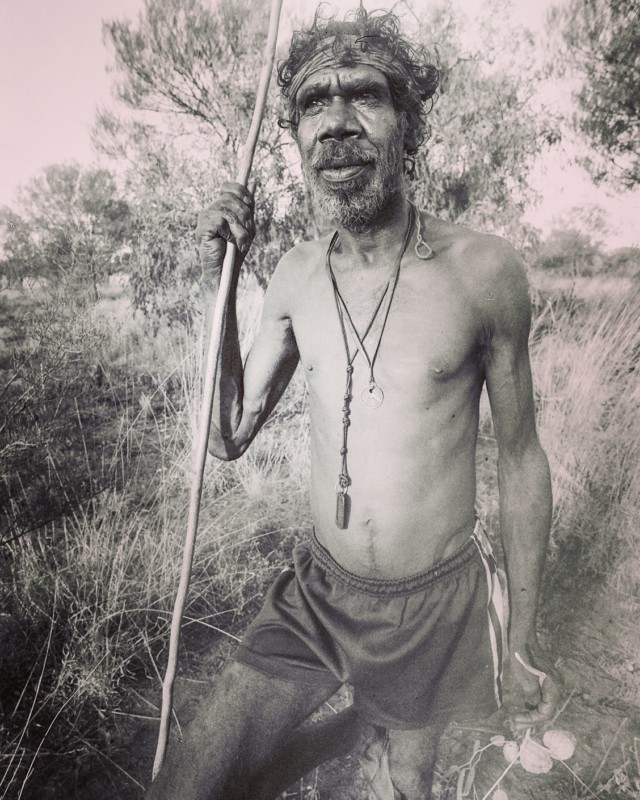

Ed Gold has spent nearly two decades working as a full-time photojournalist. Perhaps best known for documenting some of the world’s most remote people groups, Gold’s photos have regularly been published by the BBC. Despite his apparent “success” in the industry, however, Gold has been homeless for as long as he has been a photographer.

During his graduate studies in 1998, Gold found that he neither afford rent nor work a job due to how much time his studies required, so he fell into homelessness, sleeping on the floors of fellow students’ homes and in underground car parks.

“It was a brutal awakening but since then my passion to be creative has always come first,” Gold tells PetaPixel. “We all need a purpose in life and my vision for what I aim to achieve comes before anything else.”

But after graduating with his master’s, Gold began working laboring and odd jobs to make ends meet and to put a roof over his head. It was during this time that he taught himself photography with a 35mm SLR camera and 50mm lens, and he started documenting people’s lives in the countryside of north Essex, UK.

In 2002, Gold quit his job as a security guard, moved out of his apartment, and jumped into being a full-time photographer. He built his own 3-wheeled motorcycle and road it around the UK, documenting hidden aspects of old-fashioned life. He has since traveled the world to document cultures, often embedding himself among his subjects for years at a time.

“Photojournalism is what I am here on earth to do, it is my calling,” Gold says. “I have been doing it for 16 years now and will never do anything else, so I have to keep going.

“It took 10 years to properly establish myself in this profession and have invested all of my time and sacrificed everything in order to do this. I have forfeited a family and a home and almost all of my personal possessions to do this so cannot ever give up.”

![]()

Hard work, experience, and having work appear in top publications haven’t been enough to overcome the economics of the photojournalism industry.

“Supplying my work to any media organization has never been economically viable, beneficial, or rewarding,” Gold says. “I continuously ask the BBC and others for commissions and always seek to join photo agencies but nobody is interested in taking me on despite my work being more than good enough.”

“The most I can earn from a news piece has so far only ever been $700, and this usually works out to 10% of my overall travel expenses. I never actually manage to earn a wage for myself and on all my projects manage to recoup only my travel expenses by doing manual jobs.”

While in Alaska, he chainsawed birch wood for two weeks in -40°C temperatures simply to repay the pilot that flew him out into the bush. In Australia, he painted the outside of a house to pay for food and shelter.

![]()

Gold has become a traveling photojournalist who doubles as a factotum, or general handyman who is able to do all kinds of work, from welding to arborist to painter to cook.

![]()

“How many other people are doing this?” Gold tells The Guardian. “I’m giving people a voice who don’t normally have a voice, and that’s what’s the most important thing to me.”

Gold believes that there are ways the photojournalism industry could be changed to allow photographers such as himself to make a living from their craft.

“Just like I believe that privatization is wrong and nationalization has always been the way forward I believe that a nationalization or even a globalization of photographers would be a way for them to make a living for their craft,” Gold says. “The industry should pool photographer’s talents and form a hub where jobs are shared out according to what their talents are best at.”

“These days anybody who owns a camera or smartphone is a photographer and can supply media with their images for publication. This has completely devalued the skills base and watered it down to a level that now makes it impossible for the ‘professionals’ to get by.”

“It’s only because I have established a name for myself within the industry after more than a decade of intensive work that my images are used as much as they are. Otherwise, if I were starting out it would be almost impossible.”