The Economic Realities of Editorial Photography

![]()

There are as many career paths in photography as there are food pictures on Instagram. The difference is that on Instagram, the pictures are posted for fun. When it comes to a career though, pictures are produced for profit. At least that’s how it’s supposed to be.

There is no denying that the business of photography has changed recently and so has the landscape of the clients that need pictures. From the dramatically slashed budgets at national magazines to the recent layoff of the entire photo staff at the Chicago Sun-Times, editorial photographers in particular are finding themselves questioning a marketplace that has devalued photography to the point where it has often become unprofitable to work in the editorial market — particularly if you’re a freelancer.

For example, if you were to shoot three days per week — one day for the New York Times, one day for Sports Illustrated and one day for the AP — you’d make around $1,050 for that week. If you could do that every week, a 50-week income would be around $52,500 per year before taxes, retirement funding, health insurance costs, equipment acquisition and marketing expenses.

![]()

But, if you instead work the same three days a week for the $100 per assignment offered by some photo agencies, your annual gross pay would be around $15,000. Once you deduct all of the above expenses, your income would actually place you below the federal poverty line. And, since the agencies that pay at this level often take ownership of the images as well, there is no resale rights retained by the photographer and no residual income to make up for the low creative fee.

Another reality of editorial work is the time required on the front and back end of every assignment. Research, emails, phone calls, packing, travel, image processing, and even uploading digital files all consume time and those cumulative hours are often unpaid because the work is considered to be included in the fee. Sometimes, those hours can stretch into days in the case of portraits that require arranging for a studio or location, obtaining permits, hiring a make-up artist and wardrobe stylist, finding a trusted assistant, and sometimes making travel arrangements to another city. Some editorial clients will compensate you for both the pre-production work as well as the post-production processing, while some will see that time as just part of the job.

Does all this mean that it’s not profitable to shoot editorial work? Absolutely not. It simply means that in order to remain profitable, you should consider two critical factors: The clients you’re working for and the subjects that you shoot.

For example, an assignment to shoot Bruins defenseman Zdeno Chára for a national magazine will have a budget that pales in comparison to the same shoot done for someone like Reebok. The work involved might be similar, but the magazine shoot might have a budget that’s just a fraction of the Reebok shoot.

![]() While the editorial shoot might offer you lots of creative freedom and the opportunity to have your work displayed in a national publication, the Reebok shoot will offer you a paycheck that will likely be equivalent to more than a week of shooting for a national magazine. It’s a tradeoff for certain, but it’s one that photographers willingly make for the creative freedom of editorial work.

While the editorial shoot might offer you lots of creative freedom and the opportunity to have your work displayed in a national publication, the Reebok shoot will offer you a paycheck that will likely be equivalent to more than a week of shooting for a national magazine. It’s a tradeoff for certain, but it’s one that photographers willingly make for the creative freedom of editorial work.

Who you’re shooting is also important. If you make a wonderful portrait of some guy named Steve James, you’ll be paid a nice creative fee and that will likely be that. But, if you make a portrait of some guy named LeBron James, you’ll be paid the creative fee and you will likely make many times the creative fee by relicensing that portrait around the world.

Simply stated, LeBron James is valuable, and Steve James isn’t.

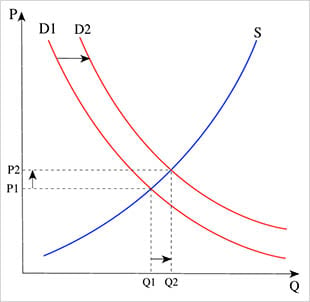

This is fundamental supply and demand and nowhere is it more evident than in the secondary market for images. For example, if you have a great picture of Dodger sensation Yasiel Puig swinging a bat, you’ll have what dozens of other photographers already have (large supply) which reduces the value everyone’s pictures in the secondary market (low demand). But, if you have a lit portrait of him and that portrait is really good, suddenly you might be one of the few who has something rare (low supply) that everyone wants and is willing to pay a lot of money to use (high demand).

The last economic reality is that every photographer has the chance to differentiate himself or herself in the way they provide images to their clients. As an example, many people can shoot game action, but how many of them are willing to mount multiple remote cameras in addition to the camera they hold in their hands?

How many solve all of their own problems and deliver fine images without ever telling the client about the many obstacles they faced on the road to getting those images? How may are grateful for the assignment and mindful of the needs of the editor, rather than just shooting whatever comes into frame?

These are opportunities to make yourself the photographer that editors have on speed dial when they need someone that they know will deliver the goods.

The editorial market is certainly more competitive than ever. But, by choosing your subjects and clients wisely, retaining the resale rights to your images, and being the kind of photographer who is a pleasure to work with, the market can easily be a very profitable one.

About the author: Joey Terrill is an advertising and editorial photographer with clients that include American Express, Coca-Cola, The Walt Disney Company, ESPN, Golf Digest, Major League Baseball and Sports Illustrated. Visit his website here. This article originally appeared on SportsShooter.

Image credits: Photographs by Joey Terrill