20 Years Digital: A Migrant’s Story

![]()

It occurred to me last night that 2015 marks my twentieth year as a digital photographer. I suspect that many of you geezers reading this (i.e. those of you over 40) are approaching or have already passed a similar milestone. You’ll probably agree with me that it’s been quite a roller coaster ride, one that my younger readers might not fully appreciate. So like any other two bit amusement of questionable soundness, I feel it’s my responsibility to post the following notice right up front:

YOU MUST BE AT LEAST THIS TALL TO ENTER!

I know many of you roll your eyes whenever codgers like me start heading down memory lane. I know we sound like the old pooperoos you’ve read about in history books (sorry, I mean on Wikipedia)– the ones who voted for Nixon and think that on-camera flash was so much simpler back before all this TTL crapola. In many ways, I am one of those guys, at least when it comes to TTL. Nixon was a crook.

But I also like to think of us as having something in common with the farm laborers who lived through the dustbowl and the Great Depression of the 1930’s– we were forced by economic necessity to migrate to where the work was. Even as the “Y2K-alypse” approached, the shining land of opportunity was once again California. This time, however, it was the fruits of Silicon Valley that held the promise of prosperity, not fruit picking in the Central Valley. And this time, the grapes of wrath were being squeezed out of little yellow boxes back home.

You young bucks are known as “digital natives”– you were born binary, and may have even live-tweeted your passage through the birth canal. You take today’s technological horn o’ plenty for granted, because digital photography is the status quo for you, the same way that traditional photography was once the status quo for us. It’s part of the fabric of the world you were born into, it’s what you learned early and know well.

![]()

And you have so many choices! Full frame or half frame, mirrorless or reflex, zoom or prime, Rockwell or SnapChick, pork pie or fedora, and yes, even digital or film, at least for the time being. All that choice may even cause you to skip to the next article at this point. Be my guest, it’s probably about drones.

But the choice that so many professional shooters faced in the 90’s was much more simple and stark: grow or die. I was one of them, and this piece is about that.

When I was freelancing twenty years ago, I was hired to shoot a rush catalog project for Filenes, a large New England department store chain and the flagship of a much larger national department store conglomerate. I perked right up when I heard that they had been beta testing early Phase One camera backs for a couple of years. I was in my late thirties, and while I wasn’t crazy about the mysterious new technology, it was hard to deny that change was on the near horizon. With no desire to look for a new career, I showed up at their vast Boston studio on the first day of the shoot, intrigued.

I peeked thru an opaque black curtain surrounding one of the sets, and was nearly blinded by three 2000 watt HMI hot lights positioned very close together behind scrims at one end of a white plexi shooting table. Once my eyes adjusted, I walked in for a closer look.

The photographer, Larry, was sitting on an apple box with his arms and head squeezed inside the scrim tent. A 4×5 Sinar P2, accordioned out with about two feet of bellows extension, was hanging directly over his head from a 12 foot Foba camera stand. A large PhaseOne back was in place behind the camera’s groundglass, tethered with a heavy SCSI cable to a teal and gray PowerMac tower and 19” CRT monitor.

![]()

Sweating profusely and swearing occasionally, Larry had stripped down to a “wife-beater” undershirt and was wearing a pair of ProPhoto-branded sunglasses that apparently shipped with the lights. He had taped a homemade cardboard visor across the top. He was trying to get a diamond ring to stand up using a tiny wad of sticky wax, but the intense heat from the HMI’s melted the wax, and the ring kept falling over.

That was high end digital photography in 1995, and that was what I was going to have to get used to.

I successfully shot the rush catalog project on film that weekend, which led to a lot of freelance work with Filenes over the next year. They provided on the job digital training, and when the studio manager offered to create a new full time position for me a year later, I thought it over for about 30 seconds, then held my nose and jumped in. Just like that, I became a digital photographer.

The performance of the Phase One backs improved markedly with the next generation, and we happily offloaded the HMIs to a local video production company. Larry kept the sunglasses for the beach. We replaced them with much more user-friendly Arri hot lights and Kino Flo fluorescent banks. Because the Phase One backs were essentially small scanners and could take as long as three or four minutes to capture an image at full 100mb resolution, studio strobe was out of the question.

While our fashion shooters stuck with film for a few more years, the product studio went fully digital shortly after I was hired. I adapted to the new normal pretty quickly, but the guy who ran our in-house E6 lab initially denied the inevitability of progress. Just like when Henry Ford opened up his first shiny dealership with balloons and babes next door to the village smithy, he seemed to be literally whistling past the graveyard when he came to work. There were fewer and fewer sheets and rolls of film to run every day. But in the age old tradition of enlightened self interest, instead of following his beloved processing line into the dumpster, he taught himself Photoshop and evolved into a fastidious digital retoucher in Filenes’ imaging department.

One big hurdle we all had to get over was how we shot complex arrangements of objects. Even with the creative potential of Photoshop and our state of the art digital camera backs, I seemed to be the only guy in the studio who questioned why we were still hot gluing artful stacks of wristwatches together, or stringing up “dancing” pairs of shoes with lead weights and monofilament fishing line. Or worse yet, handing off multiple shots to be assembled by someone else later. With film, there was no other way to do it. But it no longer had to be done that way with digital, and all the grand masters of digital photography at the time seemed to agree with me. I set out to become the studio’s composite guy, and eventually got pretty good with Photoshop’s pen tool and layer masks.

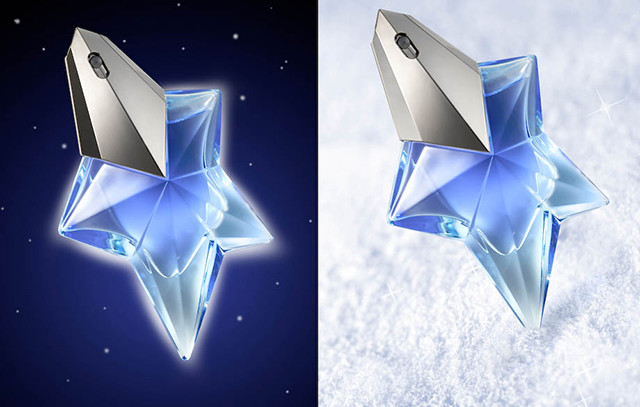

With some careful previsualization and planning, gravity became an ally instead of an enemy whenever I had to make a playful shoe shot. By cobbling together hunks of plexiglass, cardboard and Rosco Toughspun, I built custom lighting rigs that provided perfect illumination for difficult transmissive and reflective objects like fragrance bottles, watches and jewelry. Backgrounds were almost always shot separately or created digitally.

After awhile, my colleagues in the studio embraced and expanded on these techniques, and our art directors and designers began to expect them. By the time we wrapped things up in 2006, digitally assembling product illustrations from multiple shots on-set was standard operating procedure. I know these shots don’t look like much today, but back then, for a department store, they were pretty revolutionary.

When Filenes closed nearly a decade ago, I moved on to teach at vocational schools, and have shared my experiences with hundreds of students who want to take their own swing at a career behind a camera. Nothing makes me prouder than to have played even a small role in helping someone begin a new career, but the business has changed dramatically over the course of my working life. Just like when I realized that it would no longer be good enough to simply turn over a bunch of beautiful 4×5 transparencies to an art director and then trust that they can figure out how to put the pieces together, commercial photographers today need to bring a much more diverse skill set to the table.

My hope for the immediate future of vocational photo education is that more highly accomplished digital natives be put to work teaching contemporary visual communication skills to their young peers, the types of skills that are in demand now, not just the ones that photographers learned in the last century. There are plenty of throwbacks like me available to be wheeled out from time to time for context or to tell a good art director joke or two, but it really is important for us to pass the baton to the new generation of expert practitioners. There is simply no substitute for learning this stuff from the folks who are out there pounding the same pavement their students hope to be pounding someday.

The other night, after hoisting a couple of perfect Belgian-style black IPAs at our wonderful local craft brewery, I was feeling a little down about the future of our medium and my ongoing contributions to it. I was half seriously mulling over the possibility of putting my photography career to bed after nearly 40 years. You think about existential stuff like this with a good glass of beer in front of you.

But as I headed out, I paused for a moment in front of an abandoned 19th century grist mill next door. It was lit perfectly by the full moon diffused behind a rapidly moving mottle of clouds. It was begging to be photographed. Excited, I ran home and grabbed a tripod and my elegant little Fuji X100T, an astonishingly capable camera that I couldn’t even dream of owning two decades ago. A few 30 second exposures later, I realized that this old horse was not ready for the glue factory quite yet. Someday maybe, but not yet.

![]()