This Gallery Has Championed Photography as Art for 50 Years

![]()

The Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon, is celebrating 50 years of being a champion of photography as art. It has made a lasting impact on photographers and photography itself far beyond Oregon.

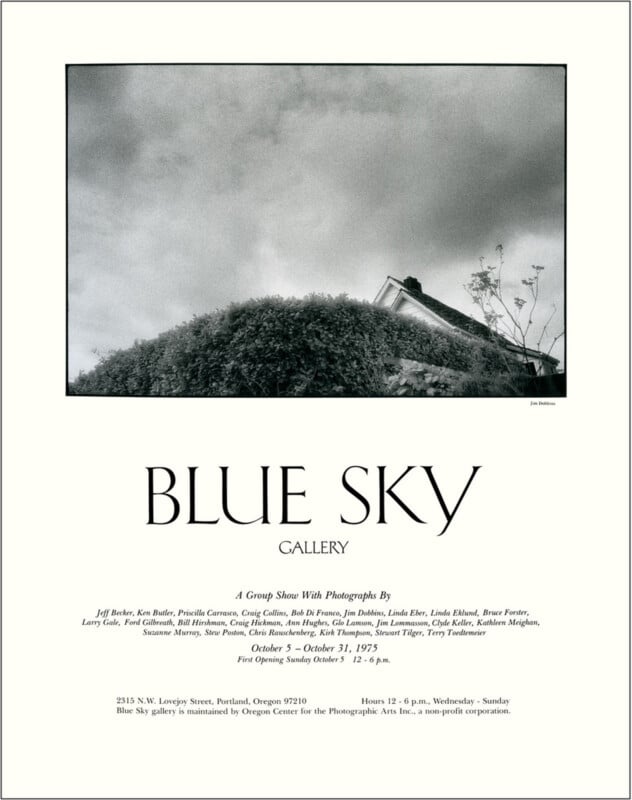

When Blue Sky Gallery opened its doors in Portland in 1975, photography was not yet widely recognized as a fine art in institutional spaces. There were no screens to scroll, no social platforms to distribute images, and no shortcuts to visibility. To see photography, you had to encounter the physical object itself, a print on paper, carefully made and intentionally displayed. Blue Sky was created to make that encounter possible, and fifty years later, it continues to serve that same purpose.

Founded as the Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization, the gallery began in a small storefront on Lovejoy Street that originally functioned as a shared studio. Ann Hughes and Bob DiFranco invited Craig Hickman, Terry Toedtemeier, and Chris Rauschenberg to join them, forming a collective of five co-founders who shared a belief that strong photographic work needed a dedicated public venue. After preparing the space and navigating the surprisingly difficult task of agreeing on a name, the gallery opened its first exhibition in October 1975.

A Necessary Space for Photography

From the beginning, Blue Sky was built on volunteer labor and shared conviction rather than financial certainty. The founders did not open the gallery with expectations of longevity or institutional growth. They opened it because there was nowhere else for this work to be seen at the time.

“The founders believed there were many exceptional photographers, some well known and others just beginning, who were creating exciting work and needed a place to show it. At the time, there was no internet and no way to view photographs on screens. If you wanted to see photography, you had to see actual prints on paper, in person. Creating a gallery simply felt necessary. Everyone involved worked as volunteers, donating countless unpaid hours because they believed the work mattered and needed to be done. As the gallery grew, other dedicated photographers also stepped in to help support its mission,” co-founder Craig Hickman says.

That belief shaped the gallery’s guiding principles from the outset. Blue Sky never charged admission, never charged artists to apply for exhibitions, and adopted a philosophy that still defines its operations today: never charge for anything you can give away. This commitment to access became one of the gallery’s defining characteristics and a key reason it attracted artists from across the country.

Building an Identity Beyond Its Size

Although Blue Sky’s physical footprint was modest, its presence felt far larger. A significant reason for this was Ann Hughes’ background as a graphic designer. Each exhibition was accompanied by a carefully designed poster that gave the gallery a distinctive and professional visual identity. These posters, combined with a rapidly growing mailing list that reached national photography organizations and artists, created the impression of an institution far more established than it actually was.

Few people realized that the original gallery space was no larger than a freight elevator. What they saw instead was a program that treated photography with seriousness, intention, and care.

As the gallery grew, it moved through three different locations before eventually settling into its current home in Portland’s historic DeSoto Building, a space Blue Sky now owns. Ownership marked a significant milestone, providing long-term stability without compromising the gallery’s independence or values.

The Second Decade and a Gallery Comes of Age

While Blue Sky’s core identity largely formed in its first 10 years, the period from 1985 to 1995 marked a period of maturation. In 1987, the gallery became a primary lease holder for the first time, transitioning from subletting space to providing a home for other arts organizations.

“We kind of went from being the child to being the parent,” co-founder Chris Rauschenberg says.

That decade also reinforced the gallery’s commitment to consistency and rigor. Weekly in-person meetings were established early on as a practical necessity in a pre-digital world. More than 2,600 weeks later, those meetings continue, now in a hybrid format, as the Exhibition Committee reviews submissions and determines future programming.

“We spend an hour and a half to two hours looking at work and deciding what to exhibit. The hard part is that even with presenting over twenty shows per year, there is more excellent work being made than we can show,” Rauschenberg explains.

The second decade was not without challenges. Political attacks on arts funding in the late 1980s led to the loss of support from the National Endowment for the Arts. At the same time, Blue Sky continued to present exhibitions that responded directly to global events, including a major survey of contemporary Lithuanian photography during a period of military conflict in the region.

“Photography describes the real world and the real world can be a difficult place,” Rauschenberg says.

Launching Careers and Shaping Photographic History

Over time, Blue Sky developed a reputation for recognizing the voices of emerging photographers early in their careers. That reputation was echoed by Anne Tucker, former photography curator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, who noted how frequently Blue Sky appeared as a first or early exhibition on the resumes of photographers who later became widely known.

“When she examined resumes for a project, she couldn’t help noticing that Blue Sky kept appearing as the first or one of the first exhibitions on a large number of them,” Rauschenberg says.

Among those artists were Jim Goldberg, Joel Sternfeld, Richard Misrach, Mark Klett, Martin Parr, Larry Sultan, Jo Ann Callis, and Eileen Cowin, among many others. Blue Sky exhibited Goldberg’s Rich and Poor series three years before it was published as a book, drawing a crowd so large that visitors filled the gallery and spilled into the stairwell.

Nearly all of the gallery’s solo exhibitions by international artists have marked their first presentations in the United States, reinforcing Blue Sky’s role as both a launching point and a testing ground for meaningful work.

Community, Participation, and Public Life

Public engagement has always been central to Blue Sky’s mission. First Thursday openings remain a cornerstone of the gallery’s presence in Portland, continuing a long tradition of accessible and welcoming gallery experiences.

“Visitors appear comfortable in the space and look forward to seeing the exhibitions,” Hickman says.

Participation extends beyond openings. Over the years, Blue Sky has presented numerous exhibitions built from public submissions, including The Dog Show, The Photo Booth Show, The Worst Picture Show, and The Instant Photography Show. In celebration of its fiftieth anniversary, the gallery has revisited these projects through monthly recreations on Instagram, bridging its history with contemporary platforms.

Another point of interaction is the Second Rate Selfie Machine, created by Hickman and installed in the gallery for the past two years.

“The idea is to intentionally make technically bad photographs that often turn out to be visually interesting,” Hickman says.

The machine features roughly one hundred effects and allows visitors to print, email, or save their images, reinforcing the idea that photography remains a hands-on, experiential medium.

Looking Forward Without Losing Sight

As Blue Sky enters its next fifty years, the gallery continues to balance continuity with adaptation. While the tools, platforms, and audiences for photography have changed dramatically since 1975, Blue Sky’s role has remained rooted in sustained support rather than short-term visibility. The gallery approaches the future with an understanding that photography is both a physical object and a cultural record, and that its stewardship extends beyond individual exhibitions.

“We continually reassess how photography is changing and how the role of the gallery is evolving. Supporting photographers in any way we can is central to our mission,” Hickman says.

That support reaches well beyond the gallery walls. One of Blue Sky’s most significant, if often overlooked, contributions to the photography industry is its publishing activity. By producing a publication for nearly every exhibition, the gallery ensures that artists leave with a lasting document of their work. These publications circulate independently of the exhibition schedule, entering libraries, studios, classrooms, and private collections, where they continue to shape conversations long after the show has closed.

![]()

“Blue Sky creates a print on demand publication for every show as long as one does not already exist. We have two exhibition spaces, so that means normally we make two publications a month. In terms of numbers of titles, the gallery is probably one of the largest photo book publishers in the world,” Hickman says.

Taken together, this sustained publishing output positions Blue Sky as an influential force in how contemporary photography is archived and disseminated. At a time when many exhibitions leave little permanent trace, the gallery has quietly built an extensive printed record that contributes to the historical and scholarly infrastructure of the medium. Combined with its expanding digital archive, which documents nearly one thousand exhibitions, Blue Sky’s approach ensures that photographic work is preserved, accessible, and contextualized for future audiences.

Blue Sky was never founded to chase relevance or scale. It was founded to show good work and support the people who make it. That long view, applied consistently over five decades, continues to shape not only the gallery’s future but the broader ecosystem in which photography circulates and endures, leaving both a legacy and a roadmap for generations to come.

Image credits: Blue Sky Gallery, Individual artists as credited.