Is This Eclipse Photo #FakeNews?

![]()

Much ado about nothing or a serious ethical breach of photojournalistic norms? A debate emerged on Facebook when freelancer and Pulitzer Prize winner Ken Geiger’s image appeared in the National Geographic Instagram feed and in a slideshow on the NatGeo website. The image was a composite of multiple images created in-camera that resulted in an photo that never existed because the eclipse was never positioned against the Tetons as depicted.

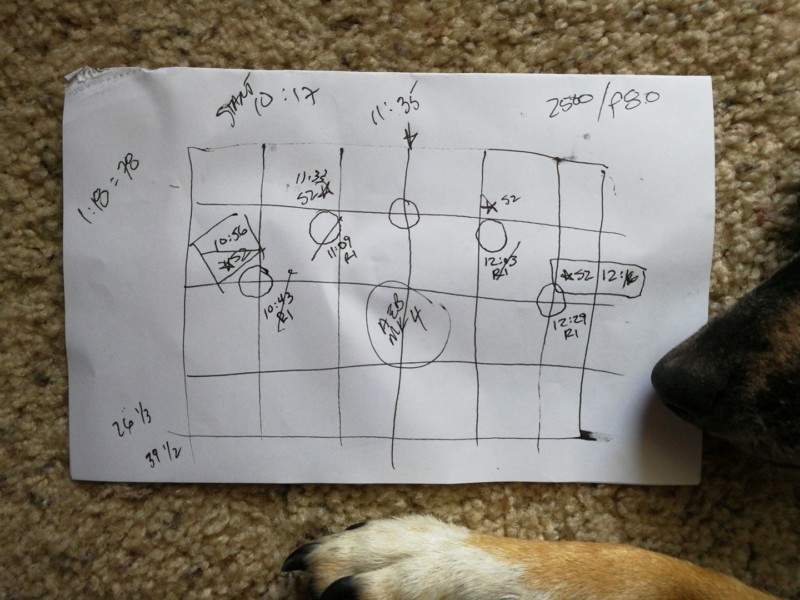

Geiger meticulously planned his image in advance using a technique similar to one he used during a previous lunar eclipse taken for The Dallas Morning News, tracking the progression of the eclipse and where he wanted it to appear in the frame, then reframing the camera to capture a terrestrial foreground.

The image was posted to his personal account with no caption, and auto-published to his Facebook account. Geiger later posted the image to the @natgeo Instagram account with the following caption:

As the sun rose over Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, thousands of people and their vehicles were jockeying for prime eclipse viewing positions. Hours later they were rewarded with a total eclipse of the sun. This image is an illustration, a composite of two frames, the morning sunrise of the Tetons and a timed multiple exposure of today’s eclipse.

Follow @kengeiger for more eclipse images. #eclipse #eclipse2017

Geiger’s aforementioned lunar eclipse image appeared on the front page of The Dallas Morning News with the following caption,

The progression of the lunar eclipse over Dallas on Wednesday night is illustrated through a series of five exposures. The first exposure, of the skyline, was made at dusk with an 85mm lens. Then, after the camera was repositioned, a 600mm lens was used to capture the four close-up shots of the moon as it moved through stages of the eclipse.

As the @natgeo account has grown to its over 80 million followers, engagement (as measured by the number of likes and comments) has declined as with most “mega-influencers.” But Geiger’s image bucked the trend, garnering over 2 million likes compared to the typical 250-500,000 likes for most images.

A number of veteran photojournalists and photo editors raised questions in Facebook threads about the ethics of the image that fell into a few categories:

1. The image wasn’t sufficiently captioned

2. Should the image have appeared under the National Geographic umbrella?

3. Composite of a scene that never existed

How Visually Sophisticated is the Audience?

Any viewer looking at the image knows it is a composite since the Solar System only has one sun. But are people being fooled into believing that this scene unfolded from a single vantage point? Does the image derive its popularity from a belief that it was captured from a single vantage point?

The Denver Post’s Senior Editor for Photography and Multimedia Ken D. Lyons said, “I was seeing an image glorified and applauded by people that I greatly respect. It was being called the greatest image of the day.” Lyons explained that even some professional photographers – arguably some of the most visually sophisticated people – were being fooled into believing this was a real scene, and they hadn’t captured it. Lyons said, “The advice I provided was they simply can’t compete with a manufactured work of art, which is what I feel it is.”

A Photo Editor’s Rob Haggart was more blunt about the perceived deception. On Facebook, Haggart wrote, “Manufactured images only have value because people think they are real or they look real. You are lying to yourself if you think it’s artistry that drives the likes.”

Photographer Alex Garcia’s admiration for the photo diminished once he found that it was a false scene. “I lose all sense of awe when I know that a photo is a composite and doesn’t reflect reality,” he said on Facebook. “More than half the awe is that our natural world produced this and can be experienced by everyone.”

Is National Geographic Journalism or Eye Candy?

“Does National Geographic magazine hold itself to those [photojournalism] standards?,” asked NPPA President Melissa Lyttle in an official statement. “Or, is it merely a magazine with pretty pictures and illustrations? Does it intend to promote high-quality visual journalism or does it vacillate somewhere between the two worlds?”

One National Geographic photographer told me that Instagram is a “different beast” from the print magazine world where a team of photographers and editors can ponder how an image can illustrate a story. He went further to say, “To think that you can make Instagram conform to that level of thoughtfulness and earnest consideration is wishful thinking.”

It’s not an unrealistic point, even if unpalatable. We are, for better or worse, slaves to the social media algorithms that drive “likes.” And in the rush to be first or garner the most likes on social media, society-at-large has tacitly accepted a wide range of manipulation from social engineering to post-processing.

National Geographic responded to my inquiry with the following: “National Geographic does not condone the manipulation of documentary photography. In instances where we publish composite photos, we aim to clearly indicate how the photo is created. In the case of this particular photo, we have updated the caption on our website to more clearly define the technique used in creating the image.”

When Technology Bends Ethics

Geiger referred to an “imaginary ethical bar” on Facebook and Lyttle mentioned an industry “bound by self-imposed ethics.” There is no doubt that the industry has developed its own ethical norms. Some are obvious (e.g. “Don’t influence the scene”), while others are more ambiguous (e.g. “My newspaper allows composites if they are labeled” vs “My paper would never run a composite).

Geiger told me that he “made the image for myself,” indicating that it was never intended to be journalistic. But at least part of the problem is one of cognitive dissonance. Many photojournalists see Geiger as a prize-winning, stalwart of the news industry. The controversy around this single image has caused some to unfairly question Geiger’s entire career. Longtime National Geographic photographer Jim Richardson cautioned such an extrapolation, “Ken Geiger has shown himself to be decent, honest and devoted photojournalist over decades of work.”

Cognitive dissonance ensues when Geiger steps out of the photojournalism box. Geiger can certainly create any image he wants, but even he seems to have trouble straddling the line – sometimes defending the image as conforming to ethical norms on a long, multi-threaded discussion on Facebook.

Former Dallas Morning News photographer Gerry McCarthy supports Geiger’s foray into “more artistic” photography but thinks it’s naive for photographers who make such shifts to not expect scrutiny based on their careers. McCarthy said, “We don’t live in a vacuum, and if the bulk of their career – at least the part that made them, or their work, well known – was done so in photojournalism, they probably should be prepared to do a lot of explaining. I’m sure it’s super annoying, but it comes with the territory.”

As more and more photojournalists turn to freelance work, they’ve had to diversify their income streams, relying on niches like commercial, wedding or art photography. Many photojournalists I follow on Instagram have been playing with technologies like Cinemagraph and Plotagraph. Is a hashtag enough to delineate truth from fiction? Does the public read captions? Even in the face of evidence, will people still doubt the veracity of an image?

“It’s hard enough in this age of ‘fake news’ to suss out what is real,” said Lyttle. “Without a forthcoming explanation, actions such as these continue to erode the public’s trust in images. Being open and honest about the process, and transparent from the get-go, could also have made this a nonissue.”

But like many ethical issues, there is nuance and competing claims. One could argue that there’s not even a consensus on what the issue really is. But as contentious as the discussion has been online, the rift has revealed that it’s a discussion that needs to happen within the industry. Technology in all forms continues to outpace our ability to understand and contend with all of the ethical issues. And we shouldn’t wait for the next eclipse to tackle them.

About the author: Allen Murabayashi is the Chairman and co-founder of PhotoShelter, which regularly publishes resources for photographers. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Allen is a graduate of Yale University, and flosses daily. This article was also published here.