Bug Photographer of the Year Under Fire for Drugging His Subjects

![]()

Macro insect photographers are up in arms this week after the title of “Bug Photographer of the Year” was awarded to a photographer who drugs his subjects for his ultra-close-up photos.

Last Thursday, the Buglife Bug Photography Awards put on by the photo contest organizer Photocrowd announced the winner of its Bug Photographer of the Year for 2021. While the contest is only in its second year, it’s notable for being one that is exclusively for macro bug photography, which is one of the most popular niches among macro photographers and a popular topic on Instagram.

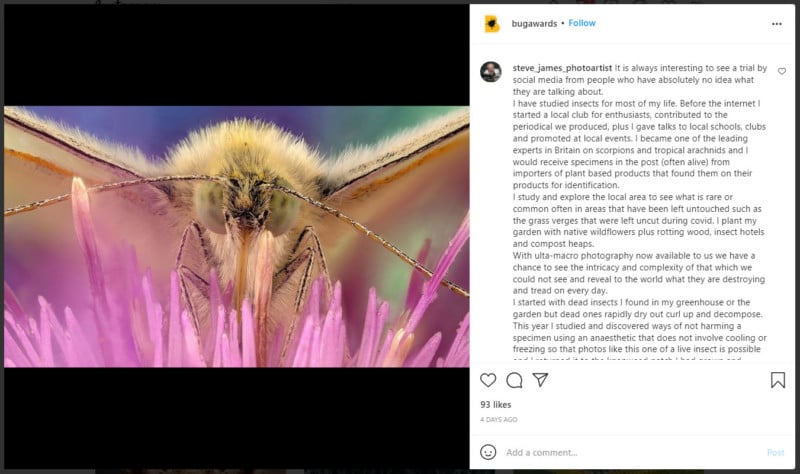

The winner this year was Steve James from Northampton, UK, a seasoned photographer who won the title of Photographer of the Year back in 1990 from Practical Photography magazine. James’s colorful winning photo shows a “Cabbage White Butterfly on Knapweed.” In addition to the title of “Bug Photographer of the Year,” James won a “host of prizes,” including £2,500 (~$3,300) in cash.

The title partner for the competition is Buglife, a UK nonprofit that bills itself as “the only organization in Europe devoted to the conservation of all invertebrates,” so it is perhaps ironic that as soon as the winner announcement was made, other bug photographers immediately criticized the choice and accused James of unethically harming wildlife to create photos.

Critics pointed to a photo James shared on Photocrowd back in July in which James revealed his new technique for getting motionless insects.

![]()

“My new technique in anesthetizing insects rather than killing them seems to work on those creatures upon them as well so I may uncover more info in time,” James wrote.

“[I]t’s a real shame to see unethical photographers be rewarded like this!” writes macro photographer Laurent Hesemans in a comment. “I really thought more of this competition and it makes me sad to see this.”

“Please stop giving credit and awards to photographers who are using highly unethical practices to obtain their images,” writes amateur wildlife photographer Kiz Ferguson of Scotland. “Anaesthetizing insects for photography purposes is immoral, dangerous, unethical and tantamount to animal abuse. This is not done to study insects for science ecology purposes. This is carried out by lazy ‘photographers’ who can’t be bothered learning fieldcraft. This is an insult to the legions of highly skilled macro photographers who shoot exceptional images without stooping to these measures.”

“Can we imagine someone submitting a photo of a drugged tiger or something to [the Natural History Museum’s Wildlife Photographer of the Year competition]?” asks photographer Seosamh Ó Daimhín. “Obviously not, so why’s it ok here?”

Bay adds that he does not believe drugging to be a viable method for deep-stacked macro photos, as they require subjects to be absolutely still for a very long period of time — up to 30 minutes or more, depending on the setup.

“If any macro photographer, with no official scientific/research purpose, admitted to killing a bug for a photo—they would be shunned from the community,” says a macro photographer who also entered the Buglife competition and who wishes not to be named. “In my year and a half of being heavily involved in the macro community on Instagram, the worst offenses I had seen were a couple of people trying to pass a dead insect they found as living. But they didn’t say whether it was dead or alive, they just left the assumption up to the viewer. That’s not that bad in the grand scheme of things. I have NEVER seen anyone admit to drugging a bug or killing one for a photo.

“We know that scientists collect and kill bugs all the time. They’re doing that for much bigger and more important reasons than our photography hobby. Because that’s what it is for most of us, a hobby. We admire the creatures and have fun with the challenges of trying to photograph them alive. Killing a bug to get its photo…it’s brutal and defeats the purpose of good bug macro.”

There are no “official” rules or laws governing macro photography, but there are many unwritten rules that many practitioners abide by.

“There is no authority that decides on the line separating ethical and unethical methods in macro photography,” says well-known macro photographer Nicky Bay, who wrote a lengthy article back in 2012 on his views. “I guess everyone draws their own line, as I had drawn mine based on the article that I had written.

“I think the line is clearly drawn when the subject is killed solely for recreational photography, with no contribution to science. I added the science bit as it is common for entomologists to kill their specimens for preservation and photography for documentation.”

As more and more critics piled into the comments section of the announcement on Instagram, James left a comment to elaborate on and defend his methods.

It is always interesting to see a trial by social media from people who have absolutely no idea what they are talking about. I have studied insects for most of my life,” James writes, explaining that he is a leading expert in the UK on scorpions and tropical arachnids and that he explores his garden and local areas for bugs that people overlook (and step on).

“With ultra-macro photography now available to us we have a chance to see the intricacy and complexity of that which we could not see and reveal to the world what they are destroying and tread on every day,” James continues. “I started with dead insects I found in my greenhouse or the garden but dead ones rapidly dry out curl up and decompose.

“This year I studied and discovered ways of not harming a specimen using an anesthetic that does not involve cooling or freezing so that photos like this one of a live insect is possible and I returned it to the knapweed patch I had grown and watched it fly away.

“I have saved more of these butterflies from death in my hot greenhouse than I could possibly count. If you think this is easy and lazy then you are an idiot as it takes months of self learning and practice.”

PetaPixel has reached out to James for comment but has not heard back at the time of this writing.

The Buglife Bug Photographer Awards rules state that animals must not be harmed by photographers, and the document bans a number of methods of stilling insects (though “anesthetics” are not explicitly banned):

It is imperative that images submitted to the Bug Photography Awards do not feature creatures who have come to harm at the hands of the photographer.

By submitting an image to the awards you confirm that any creatures in those images were interacted with during the image making process in a way that treated them respectfully and did not result in them experiencing distress, injury or death.

Methods of stilling insects that involve freezing, chemically spraying, pinning or killing them for the purposes of taking an image are not permitted in submitted images for the awards.

On Saturday, the Buglife awards published its response to the controversy in a statement on its website.

“The welfare of the invertebrates that are being photographed is of great importance to the Bug Awards, to our title partner Buglife, and to our sponsors and judges,” the contest writes. “As such we launched with a set of ethical rules that those entering the awards were required to adhere to.

“It’s therefore been a source of real sadness for us here at the awards to be receiving some criticism online surrounding our adherence to those ethical rules since the winners were announced on the 25th November.”

In its statement, the contest revealed that ethyl acetate is the chemical “some” photographers used to create their submitted photos this year.

“There are some images that have been permitted in the awards this year that use a method of anesthesia that involves placing an insect in ventilated proximity with cotton wool containing ethyl acetate,” the statement says. “This was a method that we were made aware of, and so sought guidance on regarding its ethicality, and discussed it with Buglife. We read research reports (here and here) discussing the use of ethyl acetate as a safe anesthetic approach for invertebrates when used in small amounts and for short periods, and from which they could make a full recovery.

“And we spoke to the photographer who was our first choice for the grand prize this year, and who uses this method for some of his images. We wanted to know whether or not it did result in the insects recovering and regaining full mobility and being seemingly unharmed. Based on these investigations we deemed this method to fall within the current awards rules.”

The competition says that it will continue to engage in the debate of ethics in macro insect photography so that it can draw correct lines in future years’ contests.

“We recognize that the ethical issues surrounding the photographing of invertebrates are complex, and contain a range of views, from a belief that the animals should not be interacted with in any way at all, through to a belief that it’s OK to kill them in order to photograph them,” Photocrowd CEO and cofounder Mike Betts tells PetaPixel. “We have been extremely clear since launching the awards that animals should not be harmed in the taking of images that are submitted, and so developed clear ethical guidelines and rules.

“[…] We are however extremely keen to explore these issues in more detail, to understand fully sentiments of those who have been critical of our choice of winners, and to hear all viewpoints on what should and shouldn’t be acceptable in invertebrate photography. As such we’ve launched a consultation, and welcome emails to [email protected] from anyone who wishes to express their opinion on the ethical questions surrounding invertebrate photography, so that we can issue revised guidelines and rules for the 2022 edition of the awards.”

Update: Here is a statement photographer Steve James has provided to PetaPixel:

The whole point of my work in ultra-macro is to show these creatures up close and have more sympathy for them. So I suppose I have achieved that. Most of my many failed shots are the result of the bug waking up too soon not because it died.

The criticism is mainly due to an ignorance and trial by social media. I would like to see how these people deal with lice or complain that a commercial kitchen uses a bug zapper.