Photography and Collecting

![]()

My father was the archetypal collector. He had dozens of cameras and optical devices. Tens of thousands of LP record albums, and eventually even more CDs and DVDs. There were always books, in particular series of books. And art books. He bordered on being a hoarder, but with great taste.

My older brother didn’t get the bug: he had boxes of popsicle sticks and tic tac boxes, marbles, and doodads — I think he was always thinking he’d make something out of them. My sister even less so. But I was born into my own little collections. Sharks teeth and other fossils, researched and labeled on shelves. Buttons on bulletin boards. Model kits of airplanes and tanks; I kept the box art, ordered by the model’s scale.

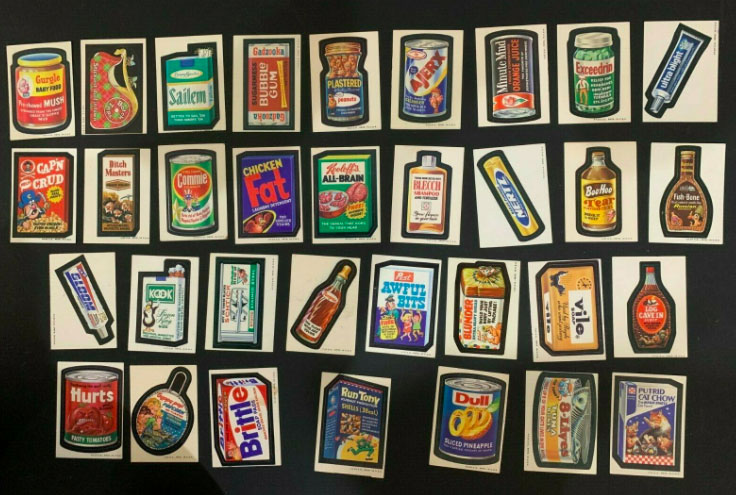

I had many series of Wacky Packages, which were product parody stickers with gum, kinda like a geek’s baseball cards. The long shelves by my bed were bright yellow with National Geographics and I organized all the maps. I took all the silver dollars my siblings left in their rooms when they went to college, and I cleaned and labeled them, and put them into a binder. They still want them back.

Stamp collecting was something that my father and I did together starting when I was young. The USPS made it easy to get a sheet of paper that illustrated every single stamp ever created, with a Scott serial number. Altogether it would be a binder about 3.5” thick.

It was easy to keep current with new releases each year, but the old ones were harder to find; on some random weekend morning we’d sit on the floor of his study and open the package of new releases and put them in their clear mounts with tongs, and add the pages to the binder.

![]()

A stamp, for most of its history, was a small engraving. If you ran your finger over them they had texture. It was a tiny slice of American propaganda and I enjoyed their Twitter-sized history.

When you’re a stamp collector you distinguish between stamps with straight edges and those with perforations, and the number of perforations in some cases. I knew about the glues and the presses, the sheets and coils, and even the inks. I could recognize Dag Hammarskjöld, the secretary general of the UN (there was a misprint issue), and got introduced to Dante (on different looking stamp paper), Eugene O’Neal ($1 expensive!), and the 150th anniversary of the Erie Canal (a lesson in graphic design), although I didn’t learn where it was until much later.

Throughout the ’70s, this was what I did with my dad, along with the rare bike ride to campus and hanging out in his office at the medical center. I was a wealth of unusual trivia, at least in part from those stamps. Collecting meant slowing down and noticing nuance. I liked looking at things through magnifiers.

Both my father’s stamp book and mine had pages and spaces all the way back to the first pair of US stamps, although my father’s book was far more complete than mine — I was missing whole epochs of stamp releases. Over those years when I was 9, 10, 11… my father was finishing a decade of collecting every single US issue, all entirely mint. I was with him for the last few he found: the set of Zeppelins, the $5 Columbian. He had a pristine collection of every single American stamp.

And so as the 1970s continued and his collection was complete, his enthusiasm for the stamps waned, replaced by a growing interest in photographs. The photos went from the decorations on our walls to boxes in closets that we’d pull out on weekends to pore through. My mom was disconcerted by the aggregation of photos but she eventually allowed my sister’s room to be repurposed as storage.

So as his attention was increasingly on photographs, he was enthusiastic to share his finds with me as I appreciated the hunting and organizing aspects of his hobby. Besides being a fan, this was my official role: building and managing the data. I loved getting a random message: “When did I get ‘Satyric Dancer’ by Kertesz? And where is it?”

There’s clearly a part of being a collector that is in my blood. But what I’ve noticed is that the very nature of taking pictures is another form of collection, and I think the essence of being an amateur photographer. I walk around the world and I save moments, I snip them out of the flow of time and space and I clean them up and tuck them away, for no obvious reason other than the deep satisfaction of doing so.

In addition to being craftsmen, picture takers are moment collectors. We savor the little details and textures and develop an appreciation for the sampling and organizing of a lifetime.

I’m a photographer not only because I’ve grown up seeing the world through a frame, not because I was encouraged to be creative and take risks, and not even because I’m practiced at crafting an image from a moment, but because I have a particular affinity for collecting. In photography, I don’t think it can be separated from the art.

About the author: Michael Rubin, formerly of Lucasfilm, Netflix and Adobe, is a photographer and host of the podcast “Everyday Photography, Every Day.” The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. To see more from Rubin, visit Neomodern or give him a follow on Instagram. This article was also published here.