Is Isolation Overrepresented in Street and Documentary Photography?

![]()

One of the byproducts of the new-wave approach to street photography, which champions anonymity, mystery, and a cinematic aesthetic, is that there is an absolute abundance of images featuring silhouetted figures and shadow play. These are the kind of images I started off creating, and there are some fantastic artists who have utilized this style over the years, my favorite of these being Fan Ho, one of the classic progenitors of this style.

Silhouettes naturally dramatize to an extent, and when used photographically they often rely on an exaggerated exposure which allows the shadows to fall to black — our eyes don’t often see silhouettes unless in very harsh lighting conditions, as they have much better dynamic range than many current cameras. It’s easy to create a silhouette effect on digital cameras, and easier still to slightly tweak exposures in Photoshop to add to this effect.

As such this style has seemingly exploded in popularity, with many photographers choosing to be driven by the light, only shooting on sunny days, and finding patches of light to compose within. Exposing for the light, or slightly underexposing, they wait by these areas for a single subject to walk through, or “interact” with this light. It’s almost it’s own genre and has as many excellent examples as it does mediocre.

![]()

I tend to refer to these kinds of images as light-architecture rather than street, but that isn’t too important. Instead, what I find interesting at the moment is the tendency of these images to capture only a single subject per composition.

Isolating individuals in light in this way can make for an interesting image, but an entire portfolio of these images contains a statement, whether intentional or otherwise. It is a lonely world documented here, as frame by frame there is no interaction between subjects, little energy, just desolate figures (or if all are silhouetted, desolate ideas of figures).

![]()

Light-architecture is easy to compose for, as all it requires is a clean background for your subject to move past, and I think that the inclination to shoot this kind of image drastically increases if a photographer takes on this commonly heard advice: isolate your subject.

This is fantastic advice when starting out because it can help the photographer to think about composition, figure-to-ground, depth of field, and focusing their story around one subject or idea in a frame. However, I think that it should be taken on board alongside a lot of other advice, and should not be seen as the thing itself.

My goal in photography is to find interesting, unique moments, and scenes, not just to isolate for the sake of following an aesthetic. I don’t have anything against minimalism as an art form — in fact, I’d say I embrace the language of minimalism in my work, but I do think it can get in the way when it comes to social commentary. Street photography can represent many things, but I think the best examples of the genre provide insight or social commentary, and limiting your outlook to only isolation means that your body of work will carry this theme as a statement, whether that’s a decision you made conscious or unconsciously.

I make an effort to make my subjects clear and distinct against the rest of the frame, with strong figure-to-ground, but this doesn’t demand the use of silhouetting. Instead I work to find interesting vantage points and background, even in crowds, to isolate my subject/s from their context, while allowing enough to fill in the story, or deliberately leave the viewer questioning aspects of it.

I can see how it would be easy to conflate the idea of “isolating your subject” and “an isolated subject.” It’s nuanced and takes some practice and understanding of the final goal to really achieve. A silhouette is an iconic visual, easy to understand and create. Something more complex, like interaction, character, emotion, energy, these take a little more energy to work with.

![]()

The light-architecture approach offers such a literal spotlight to subjects that it can be deceptively easy to shoot as many of these as you want and feel that you are creating something aesthetic, which may be true, but to me, these are often a little empty of anything beyond the light, possible geometry, and figure for scale. They are fairly easy to accomplish too, requiring no more than finding a scene and waiting for a person to pass through it — rarer still for a more interesting action to take place in that space.

![]()

It often means a lack of groups, and visible interaction between people, which can leave little to no room for an audience to project anything more than a feeling of isolation onto these solitary, ambiguous figures.

The silhouetted character often removes any potential for individuality, which removes the pressure on the photographer to seek out those interesting human moments that make up some of the most iconic street images of all time. It’s a little sad to me that to some people the entire genre of street photography means silhouettes when there is so much more potential for other kinds of image. It is not the idea of isolation but rather a specific type of aesthetic isolation that has reached this level of overrepresentation.

There are a few ways to isolate subjects in a photograph without relying on these basic scenes where there’s only one person at a time in the frame. Isolation doesn’t mean one subject per image — in fact, even the idea of “one subject” doesn’t need to be only one person (for example a group of people can represent one subject, or a collection of different groups can each be one subject). It comes down to the way the photographer’s skill at presenting the ideas that way.

Compositionally to isolate different subjects then for me the best way to start is ensuring that good figure to ground is maintained — clear distinction between the elements of a scene, with little to no overlap where possible.

![]()

Isolation through compositional skill can mean working the perspectives of a scene until the different elements fall into their place, without overlapping or interacting in important areas. This means that even a very crowded situation can feature many different and distinctly isolated subjects.

![]()

Alternatively, the tools of photography can have properties that contribute to certain kinds of isolation. For example, longer lenses offer different falloff to wider ones.

![]()

If isolation is the actual theme you want to convey then I think identifying that idea in people’s faces or body language is far more impactful than anything achievable through composition. The actual subject matter of the image counts for something on more layers than what’s offered by the language of photography, and this is where I have been spending the majority of my energy when it comes to themes of isolation or any other idea I want to convey through a photograph.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Starting out by searching for a subject or situation first, and then compositing around those elements rather than finding a composition first and waiting for something to happen inside it (usually just someone walking by) is a much better path to moving towards an image you have more control over than simply aesthetic.

![]()

Seeking out crowds and groups of people is an excellent way to practice compositional isolation without relying on the light — I do some of my best work on overcast days in diffused light. I think that a closer approach in these situations is helpful, as unless I’m shooting a very sharp lens/film combination details can be lost from a distance. There’s less definition at a distance, so a more discerning eye closer up will offer me results I am more pleased with.

Even when I do photograph silhouettes I am looking for ways to use multiple subjects to complement one another and the overall composition, but allow them all their own space to exist. This can lead to ideas of isolation while actually showcasing quite a busy situation — you represent a collection of individuals isolated from one another, rather than one individual isolated within one picture, with no other context.

![]()

![]()

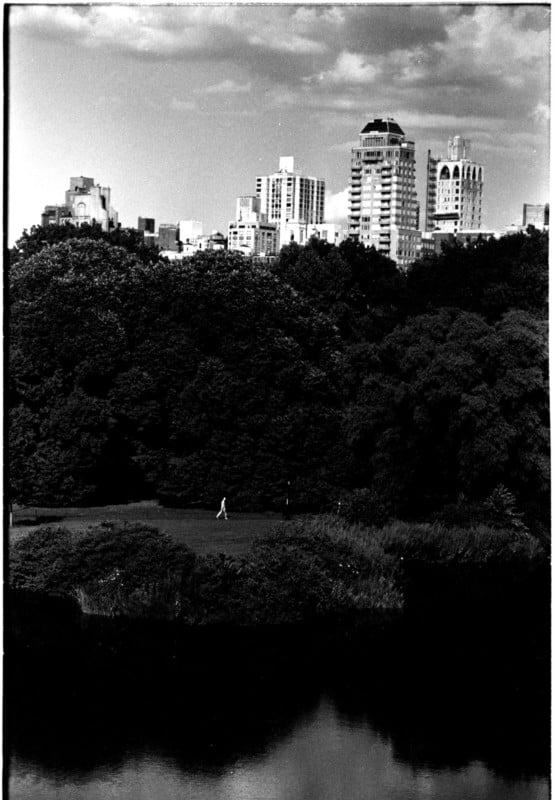

Just isolating a subject doesn’t necessarily convey anything on its own — it will be on the relationships between everything else in the frame that does this. Using things like the role of scale in the frame, to use large scenery which diminishes the subject, and looms over the frame, can have some powerful connotations. You can make the subject feel small and, in turn, communicate this to the audience.

![]()

Isolation as a theme has been really interesting to me recently, due to the pressing nature of that theme on our current everyday lives. The state of nearly universal isolation brought about by the governmental restrictions enforced to mitigate the COVID-19 pandemic means that now more than ever art that deals with the subject of isolation is immensely relevant.

Photography often becomes weighted over time, gaining new meanings and associations as the context around them changes. Many street and documentary photographs which started as snapshots now represent elements of culture and fashion which are no longer part of everyday life. They adopt different values as a result, as they have the power to frame or reframe ideas around those past states.

You may expect that this incredibly large body of light-architecture based isolation shots would take on some new meaning as a result of our current situation, perhaps as something people can relate to, or as a way to frame the discussion. Instead, I have found the opposite — that photographs of crowds, community, and interaction are reaching a nostalgic peak as people reminisce about the way things were not even a few weeks ago.

I think this is telling for what the lasting value of this kind of image will ultimately be. It really has shown that any value for this kind of photograph is in its aesthetic merit, not what it offers in terms of cultural documentation of everyday life.

About the author: Simon King is a London based photographer and photojournalist, currently working on a number of long-term documentary and street photography projects. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can follow his work on Instagram. Simon also teaches a short course in Street Photography at UAL, which can be read about here.