Photographing the Mammoth Ivory Tusk Hunt in Siberia

![]()

Amos Chapple was documenting ice road trucking in Siberia when he heard about another story. One of the drivers told him what he did in the summertime when the ice road was melted: hunting for mammoth ivory tusks.

The woolly mammoth had 7- to 8-feet-long tusks but went extinct about 10,000 years ago. Normally tusks and bones, which may begin to disintegrate in warm soil in just a decade, can last for tens to hundreds of thousands years frozen in the Siberian permafrost.

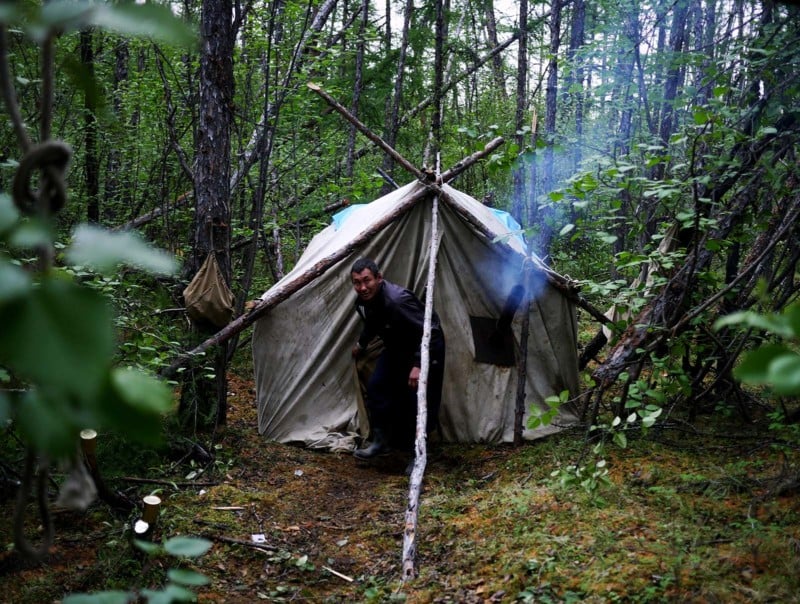

Chapple, who has shot stories in over 70 countries in the last 15 years, spent three weeks in the Yakutia (Sakha) region in the northeast of Russia, which is one-third the size of the US. He shot the story for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and traveled with a brigade of 6 people searching for this new “ethical ivory”.

“I saw three tusks [being removed] myself and there was the one that was the big beautiful 65kg [143lbs] tusk,” recollects Chapple.

The team members of the brigade knew that Chapple was a journalist but they were OK with him as he was paying for his transportation, boarding, and lodging while with them. The other men working in the valley would not have readily accepted a journalist in their midst, as they did not have a permit and their activity was illegal. Therefore, Chapple, who finds all his assignments himself, posed as a paleontologist studying the bones of extinct species.

“It took me a long time before I was able to take photographs of people because what they were doing is illegal,” says Chapple. “I kept asking ‘have you seen tusks, are there any tusks, when will we find tusks’ and eventually they got bored with me and I could start doing my work.”

“The mosquitoes made life a living hell,” remembers Chapple. “You can stop a speedboat anywhere in Siberia and within 30 seconds you can hear the first mosquito around your ear and within two minutes there will be a cloud of over 200 around your face.”

After three weeks of shooting, Chapple took a flight back to Yakutsk, the capital of Yakutia.

“I went to the back of the plane and saw a big tarp holding something, so I pulled it back and saw a big collection of tusks, some of which were 7 feet long,” says Chapple. “I grabbed my camera and started shooting. It was very low light and the exposure was probably a quarter to an eight of a second. The stewardess yelled at me and came running down the plane. I got about three frames before she pushed the camera down and said ‘what the hell are you doing?’ So I guess what they were doing was definitely not legal.”

“This cache of mammoth ivory would have been about 300 kg [660 lbs] at a local street value of $520/kg. The flight was taking place three times a week and I guess there was about $150,000 of tusks just on that one flight.”

The tusks go mainly to China and are used primarily in ornaments or just polished and sold in shops. The Guardian reported in 2010 that “…each year 60 tonnes [of fossil ivory from Russia] are exported to China, home to the world’s largest ivory market.”

Upon landing, Chapple noticed that the tusks were being loaded into a van, but he could not follow it as he had photos on him and didn’t want to get into trouble and lose them. He went straight to the hotel and started backing up the three weeks of photos that he had.

“When the story was published, I did not reveal where the place was but I included one photograph of the town,” says Chapple. “Russian bloggers were able to identify the town when they reposted the story.” After that, the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation contacted the person that he was with.

“The damage to the landscape is the most obvious visually, but to be honest, it didn’t bother me in any way,” explains Chapple. “When you are in a plane flying over this region of Siberia you see how much green nothing there is. There’s just endless empty space. So even if a hill is destroyed, it will regenerate again.”

“But the damage to the waterways, that for me, was quite shocking. These are rivers which should be some of the most pristine waterways in the world and they are so filled with mud and silt because of the hydraulic mining method that the men are using that there are no fish in those rivers.”

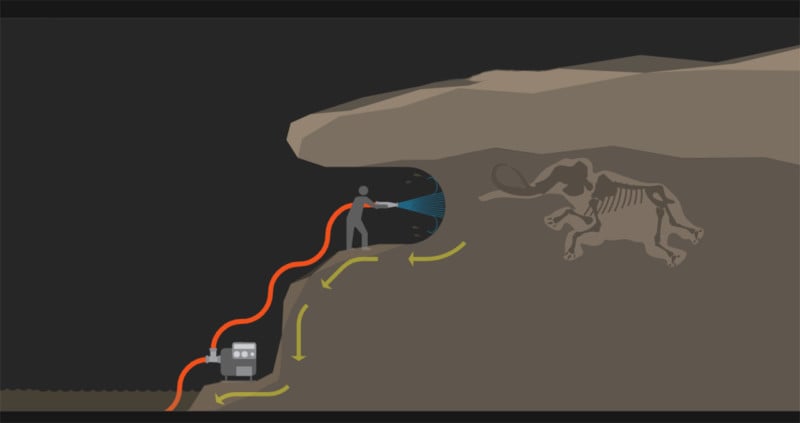

The very high-powered water jets similar to the ones in firefighting melt the frozen ground and dig cavernous tunnels up to 200 feet deep.

Besides the mammoth tusks, there were woolly rhinoceros horns also being taken out. Regarding weight, the rhino horn is much more valuable but the tusk can get up to 70–80 kg whereas the rhino horn is much smaller. One of the rhino horns was sold for $16,000 and that was about less than 4 kg. When the rhino horns reach Vietnam that price can multiply exponentially to more than that of gold, as they are believed to cure cancer.

Chapple used a two-year-old Panasonic Lumix DMC-GX8 Micro Four Thirds mirrorless camera coupled with four lenses: a 12–35 mm f/2.8 (most of the photos), a 35–100mm f/2.8, a 25mm f/1.4, and a 45mm f/2.8. He also had the Panasonic Lumix DMC-GM1 body as a backup.

“Micro Four Thirds is the best system for journalism,” claims Chapple. “If I had a big camera I could never have done this story. With this camera, I look like a tourist and that is so important when you don’t want to be taken seriously as a photographer or journalist. The system is fast and discrete. The full frame mirrorless is ridiculous as you get small bodies but the gigantic lenses completely defeat the purpose.”

Chapple carried three 32GB cards and shot 11,000 frames in full-size JPG+RAW simultaneously. At night he would download the day’s shooting to two hard drives (not SSD) separately, giving him one backup.

“At the end of every one or two days, I would pick out just maybe the 10 or 20 of the very best photographs and put those in a folder on my 13 inch MacBook Air” to give himself a third backup. Using this workflow, he has never lost any images in the field.

You can follow Amos Chapple and see more of his work on his website, Facebook and Instagram.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him via email here.

Image credits: All photographs © Amos Chapple/RFE/RL