A Review of the Panasonic Lumix LX100’s 4K Photo Mode

![]()

One of the most exciting things about capturing high resolution video with the Panasonic LX100 is the ability to extract high resolution still photos from it. Video grabbing is not a new thing, but in standard definition you were looking at stills measuring a third of a Megapixel, and even in Full HD you’d only enjoy 2 Megapixels. But with 4k video you can make 8 Megapixel grabs which is much more useful.

The key benefit to video grabbing regardless of the resolution is the frame rate, typically 24-30fps, which is much faster than even professional sports cameras operate at. Since the LX100 can record 4k at 24-30fps, it’s effectively capturing 8 Megapixel stills at 24-30fps. After capturing the video you simply go through it a frame at a time until you see the perfect moment, then extract a still image from it.

Previously to extract stills from video you’d use a player like VLC to play the video, pause it close to the desired point, then shuffle back and forth before then saving the decisive moment as a snapshot. Panasonic believes there’s an easier way so now offers video grabbing in-camera. This so-called 4K Photo mode was introduced on the LX100 and added to the GH4 and FZ1000 via a firmware update.

![]()

Enabling 4K Photo mode sets the movie quality to 4K at the highest frame rate supported by the camera – on the LX100 that’s 25fps for PAL models and 30fps for NTSC models. In my tests if the camera is set to Program mode for exposures, the 4K Photo mode also generally selected faster shutter speeds than when shooting ‘normal’ video; this makes sense as ideal shutter speeds for video are fairly slow and not ideal for taking grabs from. So long as your shutter speeds are faster than 1/100 you should be fine for grabbing portraits, and for action, aim for faster than 1/500.

Interestingly the 4K Photo mode also inherits the selected aspect ratio, so it’s not tied to filming and grabbing in the traditional 16:9 widescreen video shape. Set the LX100 to 16:9, 3:2, 4:3 or 1:1 and it’ll capture video at 3840×2160, 3504×2336, 3328×2496 or 2880×2880 respectively; note the 1:1 shape may have more pixels vertically than the 4:3 shape, but like the still photos on the LX100 it shares the same vertical field of view. Also note all of the 4K Photo modes involve a mild crop compared to normal still photos, so the lens coverage is slightly less.

When you play the videos back in-camera, you can use the transport controls to pause and shuttle back and forth one frame at a time, then press the OK button to extract a still JPEG image at the same shape and resolution as the video. Interestingly you can also do this with video filmed in the normal 4k movie modes (without 4K Photo enabled), but they’ll always be in 16:9 and if you were shooting in Auto or Program, the shutter speeds may be slower than you’d like for still capture.

I tested the 4K Photo mode with a variety of subjects: fairly static, moving slowly and moving quickly. Starting with fairly static, I filmed a portrait session and extracted the following still from it.

Now the 4K Photo mode may be capturing an 8 Megapixel image with a little scaling applied, but in terms of quality it’s actually not too far-off a native 12 Megapixel image shot normally with the camera. The nice thing about filming video for portraits is you notice very subtle differences as you shuttle-through the frames, and you also invariably capture a variety of posed and candid poses. The LX100’s continuous AF needs a second or so to catch-up if you or the subject moves much, but in general it’s a very practical way to grab some very usable images while also having a ‘behind-the-scenes’ video to go with it. It’s especially good for kids whose expressions change a lot.

Shooting at 25-30fps and extracting the decisive moment is also obviously of interest to wildlife, sports and action photographers, and I was interested to see how well the camera could handle such subjects. In short, the limiting factors are the continuous AF on the camera, coupled with the modest telephoto reach of the lens. If the subject is very close and moving quickly, it’ll invariably be out of focus on many frames. If the subject is relatively distant though and not so demanding on focus, then you’ll enjoy more success, although obviously with only a 75mm reach the subject may not be fairly small on the frame. Here’s one of a kite surfer practising – unfortunately he looked tiny approaching face-on at 75mm.

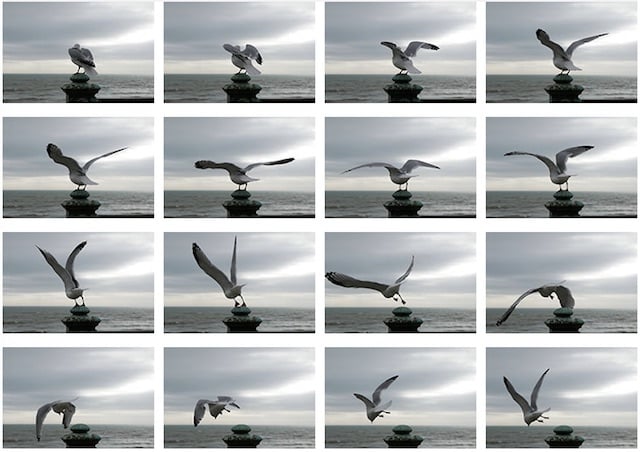

I enjoyed more success with subjects that may move quickly, but not always towards or away from you – such as a bird taking-off. We have plenty of seagulls around my home town of Brighton, so I thought I’d get them to model for me in payment for all the presents they’ve left on my car. Here’s a frame grab from a 4K Photo video, followed by 16 consecutive frames I grabbed from the video to illustrate the movement when shooting at 25fps.

Personally speaking I’m very excited about capturing stills from high resolution video, and it’s another feather in the cap of the LX100. But I also hear a lot of resistance from some photographers over this technique like it’s cheating at best, or at worst, the death of photography. That’s absolute nonsense. Traditional still capture isn’t going away – this is just another tool in the photographer’s box to capture the image they desire. But equally it got me thinking about the meaning of photography with modern gear.

Is grabbing stills from pre-recorded video so different from capturing stills from live video? After all, that’s effectively what live view mirrorless cameras do. Who cares if the video is live or pre-recorded? Sure there’s some joy in being lucky enough to capture a decisive moment with a single shot, but believe me sports, wildlife and portrait photographers don’t take any chances, and frequently rattle off hundreds of frames before then picking through them later for the best moment. Is shooting stills at 10fps somehow more ‘worthy’ than shooting video at 30fps? Is it the word video that people have a problem with?

It’s also important to point out that while video grabbers may sit back and cherry-pick the best frames from their footage, the actual video footage itself still required a degree of skill to capture. You still need to find it, compose it, light it, direct the subject or wait for the best conditions. The hard work of capture is done on-site, leaving you later reap the rewards when extracting your still image.

In this way, it’s really not unlike shooting RAW or bracketed exposures, where you capture all the information you desire on-site in the knowledge you’ll create your ideal still from it later.

Maybe you’re on-side, or perhaps still to be convinced. For me, I’m a believer. Of course I’m not of course going to swap all of my still photography for video grabbing, but I can certainly see many situations when it would be an extremely valuable tool.

As for the LX100’s implementation, I think Panasonic has done a great job of making it as easy as possible, although I wonder if capturing footage at 4k is an arbitrary limit or bumping against the actual bandwidth of the processor. If the LX100 can capture 4k video at different aspect ratios, then is there in fact sufficient processing muscle to record the entire frame? I know it’d be a nonstandard video size and shape, but if it’s just for grabbing stills, then why not? Imagine capturing 12 Megapixel images at 25-30fps without a field-crop or any scaling? I see RED doing it at 6k today and Panasonic discussing 8k in the future, so my question is whether we in fact already have the tools to do better than 4K for photos on the current Lumix lineup? It’s an intriguing thought, but in the meantime I’m impressed with 4K Photo capture on the LX100 (and its pricier siblings) — it’s a key benefit over the competition at any end of the market.

Editor’s Note: This is just one section of Gordon’s comprehensive LX100 review. Click here to read it in full.

About the author: Gordon Laing is a photographer, foodie, traveller and Editor of Cameralabs, where he publishes some of the most in-depth reviews of gear you’ll find anywhere. He’s been into photography since childhood and written about imaging over a 22 year career in journalism. He’s currently based in Brighton, England, but takes any opportunity to travel and share his adventures on social media.

You can follow all of his photography, news and reviews on Cameralabs, Twitter, Facebook, Google+, or Instagram!