The High Cost of Perfection

![]()

Walking past booth after booth at the PhotoPlus Expo in New York, I often heard camera company presenters explaining to their uncomfortably-seated, yet nonetheless-enraptured, audiences how they shot the “perfect” photo.

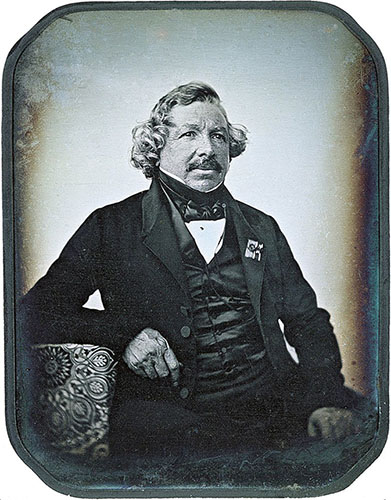

Actually, it is not hard to trace photography’s obsession with perfection. Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac’s 1840s report to French Parliament suggesting that government purchase rights to Louis Daguerre’s newly revolutionary photographic process made similar claims: “… inanimate nature, can be rendered, with a perfection unattainable otherwise, since the impressions taken with M. Daguerre’s process are faithful images of Nature herself.”

The perfection attainable through the photographic process created a dilemma: Should it be used in science for the purpose of documentation, or would it become a form of “art”?

The answer, of course, was both. Some artists quickly picked up the invention and used it as a study for a future painting; others began to use it to document life, specifically, portraits. As technology improved, so did photographers’ ability to accurately duplicate what was before them. Early advances in both the printmaking process and in devices and lenses helped capture images more accurately.

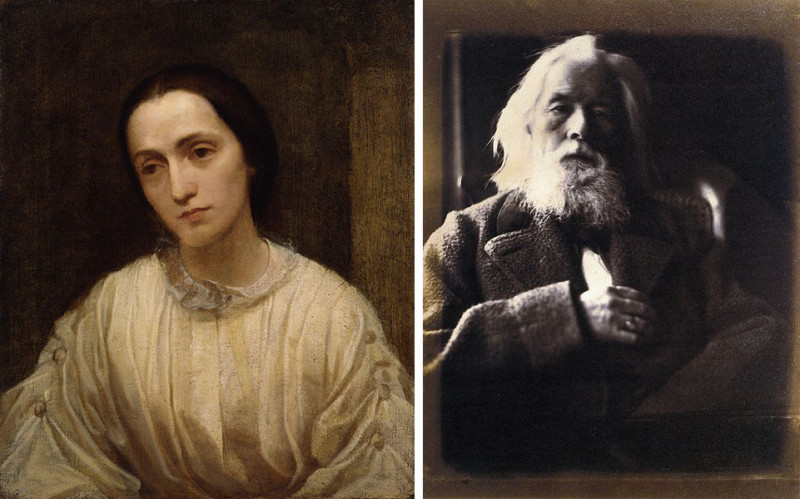

But not everyone was convinced that perfection was the real goal. Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the earliest female photographers, was often criticized for her portraits being “blurry.” She responded: “What is focus? Who has the right to say what focus is the legitimate focus?”

At the same time, European art was going through its own identity crisis. Paris became the center for art, primarily due to Napoleon’s investment in the arts and his desire to create an “Artist State.” In order to ensure the integrity of French Art, the State controlled all aspects of commercial art. To exhibit at the Salon (the only viable place that artists could sell their work) one had to have had the right training, choose the right subject matter, and create art according to established guidelines which included, among other rules, that the painting be flawlessly executed with no marks from the artist’s hand. For painting and sculpture, anyway, perfection had been defined.

Then, something happened that no one saw coming. Certain artists began to question the established rules of perfection. In 1830, Frenchman Eugène Delacroix, a renowned Salon artist influenced by English landscape artists John Constable and J.M.W Turner, began to add new brighter colors and light to his paintings and introduce more modern subject matters.

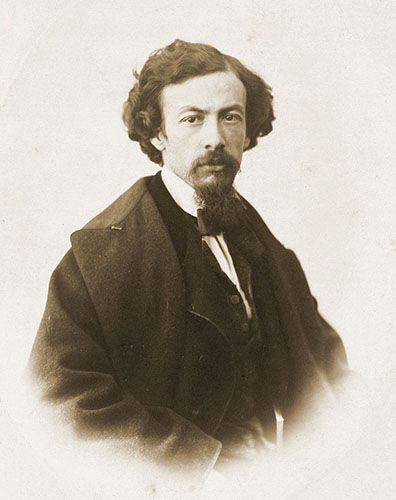

In 1865, Edouard Manet, also a classically trained artist, presented “Olympia,” depicting a classic nude but in a contemporary setting (and presumably a mistress as the subject matter). Just as controversial, he chose to “break” the rules by also presenting unconventional perspectives and unfinished brush stroke detail.

The critics were harsh and relentless in their attacks. Manet persevered, fought for his vision and continued to create art that followed his own sensibility. The French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire began to question how modern art could survive if it did not continue to evolve, both in content and in execution; then others heard this call. Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, and Pierre Renoir also began to challenge the Salon’s definition of perfection, thus starting the movement that became known as Impressionism. Art would never be the same; it had become modern.

Photography continued along its dual path, but most of the attention has focused on capturing real people and real events. French photographer Gustave Le Gray wanted to make sure photography was elevated as an art medium: “It is my deepest wish that photography, instead of falling into the domain of industry and commerce, will be included among the arts. That is its sole and true place and it is in that direction I will endeavor to guide it.”

He set up a studio and began offering instructions. After some success, however, he eventually left France with his friend Alexander Dumas (yes the author of The Three Musketeers) and continued his photographic work but abandoned teaching.

Photography, unlike painting (with its biggest innovation the paint tube that allowed painters to paint “Plein Air”), has its roots in invention. From its inception, photography (and photographers) would forever be impacted by technology — from Eastman Kodak’s invention of dry plates to color film, and the Brownie camera that made photography available to the masses. Industry took firm control over the direction of photography as it pursued its quest for perfection.

By 2000, the digital camera would be accessible to more and more photographers and, with it, the never-ending quest for bigger image files, better image stabilization and more controls that ensure images be clean, clear and perfect. And, if an image isn’t perfect enough, there is always software such as Photoshop available to eliminate any remaining flaws. So, now all you have to do is compose, shoot and edit, and you too can have perfect perfection.

But, what has happened to the art of the process of photography? Are we like the Salon artists of the 1800s, just following the rules so that we can win awards? The Impressionists still hungered for recognition, as most artists do, but they were willing to suffer for their right to express themselves, and eventually, they overcame the critics. Have we lost our willingness to suffer for our art and present our blemished, faulty, perfectly imperfect take on what we see? Have we accepted what “industry and commerce” say about what does and does not make for great photography?

Today’s truly modern world is far from perfect. We don’t see the world in 20/20 clarity. When we look at our world we find its charm in its imperfections. The rules tell us to avoid these personal brushstrokes in our work, but, following the rules without question may cost us our creative soul.

Artists through their art want to show others how to see anew, to proclaim: “This is how I see the world!” Perhaps you will say: “But, I am not an artist. I am just a photographer.” Pablo Picasso, the “great experimenter” and co-father of Cubism, along with Georges Braque, would disagree. In fact, Picasso began making photographs in the early 1900s and developed his own prints. It is well-established that photography went hand-in-hand with the evolution of his art and abstract art as a whole.

“In every photographer,” Picasso said, “there was a painter, a true artist, awaiting expression.”

About the author: Ken Mitchell is a Portland, Oregon-based photographer and President/General Manager of Lensbaby, an award-winning manufacturer of creative effects camera lenses, optics, and accessories. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.