Should We Care Who Took This Photo?

![]()

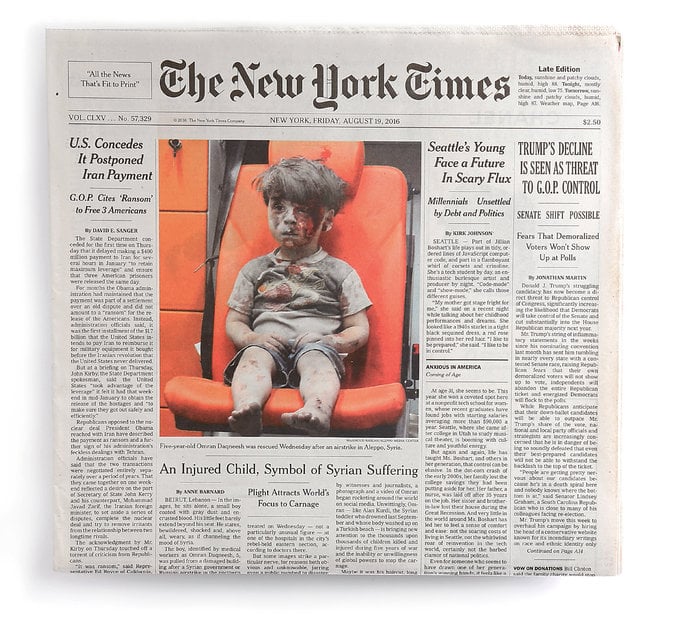

Mahmoud Raslan’s photograph of “the boy in the ambulance” from Aleppo has struck a chord with viewers in a way that we haven’t seen since Nilüfer Demir’s image of 3-year old refugee Alan Kurdi in 2015. The photo and accompanying video of 5-year old Omran Daqneesh covered in dust and blood and sitting motionless is a stark reminder of a desperate war that started the year he was born.

The New York Times photo editor Craig Allen wrote in a piece entitled “What Makes the Image of Omran Daqneesh Extraordinary?”:

One reason the photo of Omran has tugged at so many heartstrings around the world is that the boy — with his innocent stare, just to the side of the camera’s lens — triggers in many a sometimes hard-to-come-by emotion in today’s world: empathy. The photograph is an effective symbol of a war with no winners but very clear losers.

In another piece, NYTimes Beirut bureau chief Anne Barnard commented:

Maybe it was his haircut, long and floppy up top; or his rumpled T-shirt showing the Nickelodeon cartoon character CatDog; or his tentative, confused movements in the video. Or the instant and inescapable question of whether either of his parents was left alive.

By contrast, on RT.com (Russia’s state-sponsored news site), journalist Finian Cunningham questioned western media’s infatuation with the image:

The politicization of an image purporting to show a little boy with bloodied head, covered in dust becomes obvious when we step back from this emotive singular focus. Why do Western media outlets not give the same prominence to thousands of children who have been killed or maimed by the anti-government militants or US warplanes?

Cunningham’s skepticism about political motivations misses the point about what makes this photo special compared to other photos of children victims of war. But the politicization angle is a valid question insofar as photojournalism is concerned.

According to some media reports, photographer Mahmoud Raslan was previously identified in photos with members of the US-backed Harakat Nour al-Din al-Zinki group that beheaded a Palestinian-Syrian child in July. We can’t expect photojournalists to be devoid of political leanings, but should Raslan’s association with an organization that has been implicated in beheadings alter our perception of the Omran image? Or is the image remarkable irrespective of who took it?

We can take the thought experiment further. What if Raslan’s image wins the top prize at World Press Photo? What if the best civil rights image had been taken by a racist? What if the best 9/11 photo was taken by an al Qaeda sympathizer? Should we celebrate an image with a complex provenance?

I agree with Craig Allen’s assertion that Omran’s gaze conveys a sense of exhaustion and apathy in a war “with no winners but very clear losers.” In that sense, it’s apolitical. And in truth, most people don’t bother to check who took the photo. But photographers choose where to point their lens and which photos to publish, so there is an implicit point of view in every image.

In a world that’s influenced by one curated (and sometimes sponsored) Instagram at a time, the person taking the photo matters.

About the author: Allen Murabayashi is the Chairman and co-founder of PhotoShelter, which regularly publishes resources for photographers. Allen is a graduate of Yale University, and flosses daily. The opinions in this article are solely those of the author. This article was also published here.