Interview with Jim Mortram of Small Town Inertia

I first heard of Jim Mortram and his project ‘Small Town Inertia’ in the ‘Ones to Watch’ section of the British Journal of Photography. At first, I was happy that someone from my homeland, Norfolk, was making an impact in the photographic world. But of all projects I’d seen in BJP, Small Town Inertia was the only that gripped me.

PetaPixel: Hi Jim, I remember reading about Small Town Inertia in an issue of BJP and it stood out to me over the rest. Could you explain how the project started?

Jim Mortram: Thanks. Small Town Inertia was born from many elements all converging. Financially, being a carer living on benefits is crippling leaves you with zero budget. I don’t drive; I cycle or take public transport, so shooting in the immediate locale was literally the only option I had. It’s all been about sculpting negatives into positives, right from day one.

I had a very fractured relationship with where I live: a small, lost, failing, isolated market Town in East Anglia. It’s really an island unto itself within England. I moved here when I was very young, eleven, so always felt like an outsider. Being a carer only served to reinforce this sensation. Working crazy hours, over time, you lose connection with peers and find yourself in the fringe of what community there is around you. When I began the series I gravitated instinctively to document people in similar situations; people out on the edge of society.

As the series evolved I found myself becoming more involved in life again, with the people and ultimately the area. It turned a hate relationship; being stuck in a kind of no man’s land, into love. I began to appreciate everything, notice more, listen more and realised just how much strength there is. The endurance in people’s lives, balanced against the hardship, stress and heartache.

At the beginning I was using all borrowed equipment. It was a real fight. But, once the series got on the path it did, there was a natural momentum; an unseen magnetic pull that made me almost oblivious to the struggle. See, there is such a sense of responsibility that comes with shooting long form documentary, and it’s such an honour.

I’m so lucky, to be given the gifts of honesty and trust by the people I document. It’s a very real, ever present sensation. That’s the fuel. That’s what creates the trajectory: listening to the stories as they unfold, being close to people, being given these gifts of their lives and, in turn, having a platform to then share them with the wider world. It’s amazing, just amazing.

What’s strange, for myself at least, is that it’s often implied that I shoot a side of life that no one sees, that people turn their attention from. But now, there is no conscious choice of who to document. It just happens, very organically. People are all around us.

My philosophy is that everyone has a story and their experiences can inform us all about life. We all have shared common experiences. We all have so much to teach and share and learn from one another. Photography is such a powerful sharing tool; present that with testimony and you can really share.

I’m pretty obsessed with the notion of the ‘now’ of life, the right now. Even though this community is seemingly a satellite hovering around the towns and cities where ‘real’ life takes place, it’s so much more important than that. Like the people that live here; not insignificant and not irrelevant. It’s the same for everyone; wherever you are.

What’s on your doorstep is a perfect reflection of what is happening, right now. Here, we see the repercussions of policy made hundreds of miles away. A pen swishes over paper after a think tank decides what should be. In the estates and within the lost cottages and apartments; you see where those decisions lead to.

![]()

These are hard, painful times. Empathy seems to be being hunted down, hunted out of existence; culled. The Bedroom Tax. Food Banks on the rise. Financially, people are really struggling. There are cuts to services; resources are stretched to point of fracture and the people that are hurt the most are the poor, disabled and needy. They have to endure this whilst under the cosh of ever more stigma.

This series has always maintained that every day people have a right to dignity, a right to be heard and not ignored. I hate and have always hated the term ‘subjects’. I have never and will never refer to anyone I’ve been lucky enough to photograph or interview as a subject. We’re all human beings, together. I document my peers, the people around me. I’d take that notion with me whether I shot 2 miles from home or 2,000.

If you shoot a subject and you can’t get close, you’ll take photographs of someone looking at a camera. A photo kiosk can do that. To be close; you can’t fake it, it has to be real. Many times I go out to shoot and don’t even take a single image. I just listen to what’s been happening. Listening is important, so, so important.

Making photographs has profoundly taught me to shut up and listen more. I’m not interested in making images of myself, about myself, or even for myself. I’m just a conduit. This is not art; it’s a link in a chain, a chain of shared ever-informing experience. My part’s small. The person sharing their life with us – that’s everything.

What they bring to a single image, a story, is key. For those moments they are a person’s story within you – it’s the completion of the circuit, it’s where lives interact. In a world that sometimes feels drenched in apathetic, blind narcissism and escapism; I find that exchange a real place of safety, a resistance, a fight back.

PP: I’m from Norfolk as well and I can relate to the idea of the area being in a “small, lost isolated Market Town”. Do you feel that your own experiences have directed your approach to what you wanted to photograph and how you photographed it?

JM: Sure. Everything we do, every experience informs the photography; at least it does for me. I’m thankful for that. Every personal experience and the on-going education we all give ourselves is all part of the way of seeing and, more importantly, the way of relating and feeling.

Image making in the moment is very reactive to the scenario and circumstance; emotionally and technically. There are limitations and opportunities. A moment permits in terms of how close things are: physically, emotionally; when to take a step closer, when to step back.

Light. Light, can dictate everything. It’s all a big improvised dance. You can’t know in advance where it will lead you. You just try to keep a rhythm and not tread on the toes of what unfolds.

In my personal life, like anyone, there have been some extreme lows and lulls. I certainly took a few things as close to the edge as I’d want to. Life’s about learning, sometimes its just luck that permits you out the other side.

I know I’ve taken my own brushes with mortality. My own understanding of isolation, loss and pain helps me relate a lot. I don’t often feel like an outsider when shooting. There are touchstones in common; time and time again. We all cut the same. All of us.

It’s a lot like music. There are notes and scales and then the blue notes and the minors. When people talk to me about certain situations, I can recognise those melodies and that’s important. I’m not documenting from a life too far removed. it’s not about collecting butterflies y’know? I mean, I have never taken a photograph purely based on the aesthetic appeal of another person; it’s not about amassing a document with the eye of curiosity – as a voyeur, at a distance.

It’s about documenting the real life experiences that inform us all. No one gets through life without their own scars and none of us get out alive. But, if we can help each other on the journey from A to B, that’s cool with me. Some of the best help is simply just listening. I’m still amazed at the people I talk with and document that have never felt they have been listened to their whole life, by anyone, ever.

I do think my own experiences led me down a path where I was not interested in using photographing as my ‘art’, my expression. There’s no desire for it to be about me, it’s always very natural. I’ve never questioned it being a part of me; it’s always been about following the intent of the lens being pointed outwards, at someone else. It’s their story, not mine. An SLR camera has a mirror. Light reflects and bounces upon a sensor or film – that’s key for me. It’s a reflection of the reality feet away and a tool for communicating and sharing.

Photography is a powerful tool, transporting us across space and time. Any boundary you can conceive of; photography can cross it. It can take you, the viewer, into homes, moments, lives, countries, communities, loves, losses, the greatest joys and the greatest pains. As a device and medium for sharing and connecting people, photography is still peerless for me. When combined with the digital revolution and the evolution of the internet, more so now than ever.

For sure my own experiences of culture, as with any and every one, informed certain elements of the how and the dynamics. Every book, painting, film and early passion for documentary; my own father shooting in mono, developing film in a bowl in the bathroom or kitchen – it all added to the mix. It’s the same for all of us. We all make our own recipe based on the ingredients given to us and those we choose along the way.

PP: It’s clear that you find an intimacy with those involved, much like music as you said. How do you build up a rapport with those involved, with view to documenting their life, especially when they could be quite vulnerable? How do you feel the project would be different if you viewed those involved as ‘subjects’?

said I was in the gym. I thought I was up town laying on the pavement.”

JM: How? Exactly the same way in which I build up a rapport with anyone, I mean, we’re doing that right now. It’s all about interaction, asking questions, listening, responding. There’s no difference between any other encounter in life and photography, just, when photography is involved I have a camera to hand. Saying that, I always have a camera to hand.

Would it be different if I viewed the people I document as subject? Yes, a vast yes. There are many strata of documentary photography; many, infinite even ways of making photographs.

For me, long form documentary works so well because it’s an ever evolving process. You need to get closer in more ways than that which a prime lens affords. I’ve never been interested in making images of people looking or reacting to another person holding a camera; the camera has to disappear as much as it can.

I tend to shoot in two ways: portraiture and documentary. But the great facilitator is never the camera, it’s the trust. How do you earn trust in a photographic relationship? The same way you earn it in life I would say. People always know from the start of a series what the deal is.

I am very explicit in informing people about the whys and hows and it’s always their choice to proceed. Trust enables closeness beyond a portrait lens; trust is the key that unlocks a deeper exchange. If I wanted to photograph people looking at cameras, I’d shoot catalogue models.

PP: Such a good response. In some documentary projects, it feels like the photographer is an intruder, but it seems through your pictures and motives that you’re integrating with their world and them with you. How do they feel being involved in the project and sharing their stories?

JM: Thanks. I’d never want to be an intruder. What does an intruder do? Take images, literally stolen moments – that has never interested me. It’s the: “do you take or make images” debate.

For me, it’s always been making images, not manufacturing. Integration with one another is important for sure, just as it is in life – again, a musical comparison. Documentary is free form, its jazz; anything can happen without direction. You react, not dictate. Again, trust is paramount in these moments.

Making a portrait is a composition quite different, but you can always swap over the elements and dynamics of how you photograph in each situation. Sometimes I make what I’d call documentary portraits – very different to straight documentary or straight portraits. These only arise at certain specific moments though, as when shooting documentary you never want to intrude upon an event that is unfolding, subtlety is key and again, trust.

At the beginning, I asked myself a lot: why do people want to be involved? To share? In each case there are differing reasons, but, a common thread through all.

Whilst shooting the series on epilepsy it was clear to me that Simon wanted to be proactive, to get a positive out of his serious experiences with epilepsy, in his case, Atonic seizures. His being documented afforded him a platform, a place in the world to do something, take a stand, inform other people just like him what it’s like to survive, what it’s been like to have VNS surgery but also to show those that have zero experience of epilepsy what it’s like.

We have that in common, that desire to redress the balance of people assuming what someone might be like or their situation, documenting a life, a situation, informs, educates, shares, it fills the void where people rely on guessing or stereotyping. That’s also a big reason I rarely share standalone images.

Yes, a photograph tells a thousand words, but you add a thousand words to it – pow, you have no room for assumption. Viewers are empowered in their experience of the images through the most important vital element: context. Devoid of context an image can be a launch pad for a million incorrect templates to be overlayed and presenting images without context, for me, is a brutal dereliction of duty.

Other people get involved as they want to be heard, noticed. So many of us never get the chance to have our say, we are all taken for granted in life in so many ways. If we find ourselves isolated from people, in solitude, how can we ever feel like we are being witnessed?

Documentary photography is a real enabler in this respect, it’s a wonderful way of saying to people you matter, you’re not a zero. Who you are and what you’re going through counts and is not unnoticed.

I always keep people up to date with what happens after a story has been updated. If an image or story has been published, they get the copy I am sent. If there is an exhibition, I let them know how it’s gone, if comments are left, I share them.

![]()

PP: I like that one of the focuses of your work, and those involved, is to create awareness. One of the most powerful images, to me, is of Tilney1 sitting in the bus shelter. I think the picture embodies the symptoms of a schizotypal personality perfectly. Could you give a brief account of Tilney’s symptoms and how you took the picture?

JM: Tilney1’s symptoms are very clear and ever present, ever invasive. He’s consumed with ‘memory loops’; snapshots of moments from his past. Imagine an internal strobe light that flashes the detritus of a life lived endlessly. Imagine there might be a code, a purpose, a line through the very heart of all the events and shadows of your life.

Imagine sewing and stitching every element of your personal history together in an attempt to understand the present so obsessively that the past becomes your every waking moment: loud, bright, clear and in focus. Imagine you can remember everything, every detail of every experience. Imagine these are the thoughts that occupy you, inhabit you and you can’t turn their volume down.

The photo of Tilney1 is taken in his old school bus shelter. Knowing he’d spent years standing there waiting to be taken to school, all before his condition developed, gives that moment a deeper meaning for me. In those images he’s really struggling. It’s as though his thoughts are so consuming that a pause button is pressed upon his ability to interact with reality – he just shuts down.

I talk to Tilney1 maybe twice a day on the telephone, just to touch base. It’s good for him to know there is someone out there he can reach out to and I always enjoy talking with him. I enjoy talking with everyone I document.

Last year I helped him piece together a magazine containing some of his work. We’re working on getting a book put together at the moment. It can’t be rushed due to his symptoms, but his work, damn, it just grips me. They are letters home from the front line of mental illness.

PP: I think the public perception of schizophrenic disorders is the classic “hearing voices” analogy. But there are upward of six different schizophrenic diagnoses. What do you think about the state of the majority of the public’s attitude towards physical and mental disability?

JM: I’d say the average public perception of mental illness is just as misinformed and biased as it is about anything else. The crime is that one in three of us will have a brush with some form of mental illness during our lives, yet, as with so much of life there is a huge stigma to it.

Tilney1 is always worried about what people think of him; that he’s mad, that his obsessive tendencies make him a bad person. I always tell him it’s no different or more surprising than sneezing when you have a cold. There is a real clear damnation on people in our society that have mental illness.

Recently, I’ve been shooting a citizen run food distribution collective. I’d say at least three quarters of the homeless people they hand food out to are suffering from some variant of mental health issue. It’s not right; our society is so unbearably cruel and unforgiving to those amongst us, those that need the most support, the most love. Our government is worse.

Physical disability, the stigma and the judgement that gets laid upon people dealing with it is a terrible state of affairs. Our culture, especially mainstream print media and television, really impose a template of three elements: “lucky it’s not me”, “faker and scrounger” and being there for our amusement. We’ve really hit a low not witnessed since Victorian times in this respect.

Everyone knows talent shows where a raft of people get brought out, dreams however misplaced in their hearts, only to be lambasted with ridicule and solely for the viewer’s amusement. It’s a terrible trait we have as a species; this unapologetic ability to look, laugh, forget. A lot of photography these days echoes these trends; everything is there for the photographers taking, people as subjects, images not to inform but to shock, manufactured realities designed to garner a greater response from an aesthetic, rather than context and reality.

There are also a wonderful number of photographers making amazing work, series’ and projects that redress this imbalance. They champion human spirit and show things unflinchingly as they are; the good and the bad with the sole intent of sharing; not exploiting, but informing; not amusing, but empowering; not immolating.

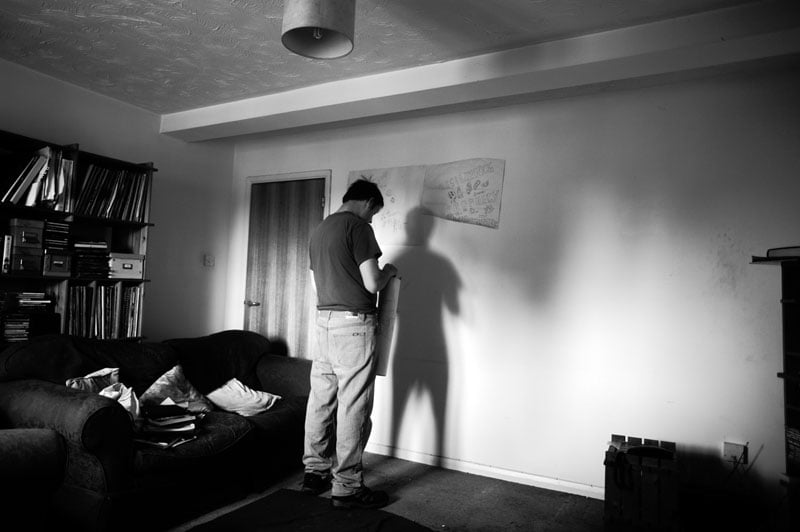

PP: Each of your pictures seems to explain both the emotion and situation of the person involved. Could you explain your thoughts on using black and white as opposed to colour? And the importance that high contrast has in the work? Do you shoot digital or film? How important is the choice to your process, if at all?

JM: Thanks. Black and white? Well, when I started, I used to use a monitor that was broken; it was only good for mono work. Having said that, there are other reasons I do have and am very aware of for shooting mono. None of them being that it’s ‘cool’ or ‘more real’.

Black and white images really emphasise composition and shapes for me. Coming from a painting background I’ve always enjoyed the way a canvas, or in this case a photograph, is divided up compositionally, and how in turn that composition can aid narrative and context.

Hockney and R. B. Kitaj are both painters. Their use of composition has always stuck with me. For example, even though I’m shooting documentary; on a subconscious level I think the compositions are reactions to the person and the situation or place I am within and I, as we all do, even if we don’t realise we are doing so, draw upon a vast pool of influence.

In my case this is a lot of painters and a lot of cinematographers. I know they are there whispering to me even if I’m not consciously saying to myself ‘this’ or ‘that’ and I like that, it feels very instinctive; an extension of self. How we see is informed by so, so many elements.

I’ve no preference for black and white over colour, or film over digital. The story always comes first. I shoot colour portraits, on film and mono with a DSLR and this is down to cost.

If I shot the amount of mono I do with colour film it’d be even harder to afford to eat than it is now. If I’m lucky, I get to shoot one roll of colour Medium Format film once every month. I’ll shoot full colour stories in the future I am sure.

I always shoot to control highlights and the trade-off is intense shadows. I’d prefer that over blown highlights. In camera, I’m shooting RAW files with everything turned off: zero sharpening, zero D-Lighting or equivalent. I just get an eye for the composition, spot meter the light I’m controlling; compose, lock focus, recompose and shoot. I shooting fully manually, that’s the most common method I use to shoot with a DSLR.

I tend to use as little post production as possible, certainly nothing that’s not comparable to working an image up in a darkroom. I use the same techniques, but digitally: a simple tone curve, simple eyedropper work (test strips) and dodge/burning when and if needed.

I mostly shoot in low light situations. Maybe one window will illuminate a room and I’m always at the mercy of the UK weather. I’m often in a dark environment, these photographs capture that.

PP: It’s interesting that you have a painterly background. Street photographer Eric Kim recently said he thinks the best editors and critics are artists such as painters and illustrators. Do you think your background has given you a different perspective, or do you see the camera as a different medium for documentation?

It’s also interesting that you left University in your third year and have since had a good deal of success. I think, in what I’ll call, a ‘degree culture’; people misinterpret qualifications with future success. How necessary do you think qualifications are in terms of being an artist?

JM: Indeed. Thankfully I’ve found a wonderful lab, Labyrinth in London, who develop and scan at a great rate and do some for some real big names in photography. As with all things, the fact that they are good people transcends everything. It helps that their quality is peerless too.

I studied fine art painting and, obviously within that, the History of Art. Most of the things I loved about art I’d found before I embarked upon my degree course and since having to quit to be a carer, I’ve been somewhat of an autodidact. The Internet is an amazing facilitator for self-education; free self-education.

For sure, my background has given me a certain perspective, but I’m not merely referring to education here, we are all the sum of our parts/ There is so much more to us than being shown other peoples work and being told to, in-turn, go off and make our own. Without the ‘life’ element, where do we draw inspiration? Empower and inform our own sensitivities?

All the great joys, losses, madness, messes and pains of my life have stood me in better stead than a lecturer telling me to “Go check so and so’s work.” However, photographic courses are geared very differently to a fine art degree, with much more emphasis on how to survive as well as nurturing what and why to shoot. Falmouth run an amazing course, as do Gloucester, with lecturers that really know their stuff and really, really give a damn.

We are all different; we get to choose our path as much as we stumble our way blindly, chaotically bouncing into the seen and unseen situations. Life happens. I don’t know if qualifications have anything to do with being an ‘artist’ and in no way do I, or shall I ever consider myself an artist. Most of my favourite painters and photographers never studied a day in their life; they just lived it and did it.

However, you have to balance that with the idea of being an artist and having a career. From my experiences; talking with students of photography today and their lecturers, there does seem to be a good balance with teaching and really making an effort to facilitate students in their survival in the real world.

For me, things just happened the way they have done, all the life, all those ingredients that led to making images in the first place. Finding photography, for sure, saved my life. It’s been a rough ride to this point, but I’d not change a thing. Every experience is like collecting a new colour to add to the palette of emotions that you can then re-direct into other situations and to photography, and I’m not talking tech wise, I’m talking how you feel what you shoot, how you relate to it, why you want to shoot and what you do with it once it’s shot.

Learning can’t just be about what f-stop, what shutter speed; we’re all always learning within our lives. It all has to go back into our photography. It’s a never ending process and should not be a finite experience. And the notion of being ‘educated’? We are learning from the first photograph we make to the last one we will ever make. Patience is key.

If you quit half way along the journey, you’ll never know what’s around that next part of the maze ahead, and it might be a pitfall or paradise. Quitting is such a murderous act, it kills possibility.

Photography has never felt like a chore or a discipline for me, it’s always felt like the natural outcome of every experience in my life that lead up to making images. What is photography for me? A process of recording light that just travelled 92,960,000 miles in eight minutes from the sun, to bounce back to the upon sensor or film that’s directed directly at what’s transpiring there.

Most importantly of all, it’s a device and process that records moments, lives and events that can then be shared; shared in the now and shared for the future. Our photographs will always outlive us all. I’ve always viewed images as a document, as reflections both within the now, for the now, and messages in bottles for a future undecided and those of us yet to be.

It’s also really important to think on this notion of success, what is that? Money? If so, then I’m a spectacular failure. For me the success is in sharing the stories and sharing time with the people I’m lucky enough to shoot and the things they teach and share with me that I couldn’t have been taught at any place of learning or buy with any wage.

Success has been getting to know so many, many amazing people through photography; incredible photographers, curators, editors, book makers, publishers, writers and people that just flat out love, really LOVE photography in all its forms. There is a community out there that’s so giving and supportive and so talented; in those respects, I’m the richest and luckiest man alive and I more than know it.

PP: I totally agree with what you’ve said. I think those who are extrinsically motivated are going to have a difficult time, especially if they’re working in these sorts of environments. It leads to the question, would you rather be happy and poor or unhappy and rich? I know what I’d rather.

I was wondering if you could talk me through some of your influences and inspirations? No matter what they are. I watched the film American Gangster recently and the colours and imagery in that film made me want to photograph more than say, sifting through a photobook.

JM: Inspirations, sure. John Pilger, the documentary maker for his lifelong pursuit with such integrity of truths and justice. In cinema, the Dutch cinematographer Robby Müller who shot many films with Wim Wenders.

Cinema has always been a huge inspiration, that amazing pairing of narrative with image. Other cinematographers such as Gregg Toland, Robert Burks, and early British kitchen sink dramas too.

The directors Tony Richardson, Karel Reisz, Ken Loach and Mike Leigh have all moved me greatly. Painters such as Hockney, R. B. Kitaj and Frank Holl. The sadly just departed Iain Banks; Alan Sillitoe and Alan Bleasdale. Inspiration comes from so many amazing people all the time.

Fundamentally; outside of life and the people I document, my biggest source of inspiration by other artists has come from the tradition of those working around or within Social Realism.

Photographically, I have so much respect for Eugene Richards, Chris Killip, Giles Duley, Brenda Ann Kenneally, Justin Leighton, W. Eugene Smith, Walker Evans, Don McCullin and many, many more. And all for their attitudes towards shooting, their ethics as much as the amazing photography they produce.

![]()

PP: Considering all this, how did Small Town Inertia, and you, come to prominence?

JM: Slowly and all via the Internet. For a few years I was sharing via the usual social media platforms. Then, I decided to make the whole series a blog. In the first 12 months I began to get featured on numerous bigger blogs. aCurator and DuckRabbit have always been very supportive, for which I am eternally thankful for as it’s taken the stories to evermore people.

Exhibitions, publications, features and recently, the first of a series of books with Cafe Royal Books happened but it’s important to stress how organic this has been. Momentum takes time to gather speed and I’ve only said yes to situations and people I’ve really trusted and really wanted to do things with.

Twitter has a wonderful community of photographers and other folk from, or around, the photographic world and I’ve come into contact with so many amazing folk there. I’d never had a website and Mike Hartley (and his wife Julie, who runs aCurator) of the website design company BigFlannel offered, so, so kindly offered, to sponsor and design from scratch, a website for me. It’s been a real labour of love taking Small Town Inertia’s web presence to where it stands right now. Mike’s been amazing and has taken the images and text and really empowered them.

PP: So really, it’s a good story about embracing new technology and social media – always a good thing. I know you help to raise money for those involved with your projects. Could you talk a bit about that and how you fund your own work?

JM: Very much so. The Internet has long had its detractors and current events have shown, more than ever, its abusers. But it’s also the closest the human race has ever come to having a tool to facilitate a collective consciousness; we can all connect, share and experience. It’s right there 24/7 at our fingertips, if our own intent is there to step up and make use of it.

Funding, that’s a tough one, really hard. Being a full time carer at home prohibits me from Arts funding or grants. I get help from friends, some really amazing friends. I’ve had gear and film donated – incredible; blows my mind and touches my heart. Without these acts of amazing generosity I’d not even have a camera to use full time, let alone keep the project going to the extent it is.

Every week some of our food budget goes on shooting though, it’s an inconvenience (and makes for a good diet regime!) but never one that feels like a sacrifice, it always feels necessary.

My way of giving back is to be proactive with images and stories whenever I can. Mike Hartley of BigFlannel turned me on to an amazing site: HopeMob. @hope is a great site to raise money through for causes and is a platform I’ll continue to use. I see the whole ‘deal’ as a cyclic one; one we are all involved with and investing in, all helping one another out.

PP: I think that’s a great point to finish on. Is there anything else you’d like to add or say that we haven’t covered yet?

JM: Well, the biggest thanks is to my partner Laura and my father Dave, for supporting and standing by me. I feel I’ve only scratched the surface of all the stories to come, so I’m looking forwards to working on them.

PP: Thanks for everything Jim. It’s been great getting to know you and delve more deeply into your work. Good luck to you and everyone involved in your projects.

Update on October 16, 2013: Here’s a teaser for the Small Town Inertia documentary film:

I’ve read a lot of interviews where the photographer or artist comes across as aloof or pretentious. This is definitely not the case with Jim. I think his self-effacing attitude is what makes this project so powerful. The intimacy between Jim and those involved is translated in the imagery and text. I get the feeling I know each person from each picture and each story. I think the regularity of the work and his willingness to share it is really testament to his selfless motives.

Personally, I feel that this is one of the most important documentary projects currently around. There is a great deal of misconception and prejudice about those with physical and mental illness; I’ve witnessed it first-hand many times.

The psychologist Gordon W. Allport developed the contact hypothesis. This is the idea that interpersonal contact between groups can reduce prejudice and misconceptions by reducing previous overgeneralizations and simplifications. In terms of learning about those on the “fringe of society”, this is that contact.

You can see Jim’s work on his website and on Tumblr. You can also connect with him on Twitter.

If you’d like to donate and raise money for David’s audio scanner, go here. Finally, you can see some of Tilney1’s art here.